An amateur archaeologist from Brandenburg has discovered a trace of Celtic gold.

Not far from the village of Bayz in the German state of Brandenburg, the amateur archaeologist Wolfgang Herkt found ten gold coins. Though it would be stretching to call him an amateur: Herkt is honorary curator of the Brandenburg State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and the Brandenburg State Archaeological Museum. After he reported the find to his colleagues, archaeological excavations began at the site.

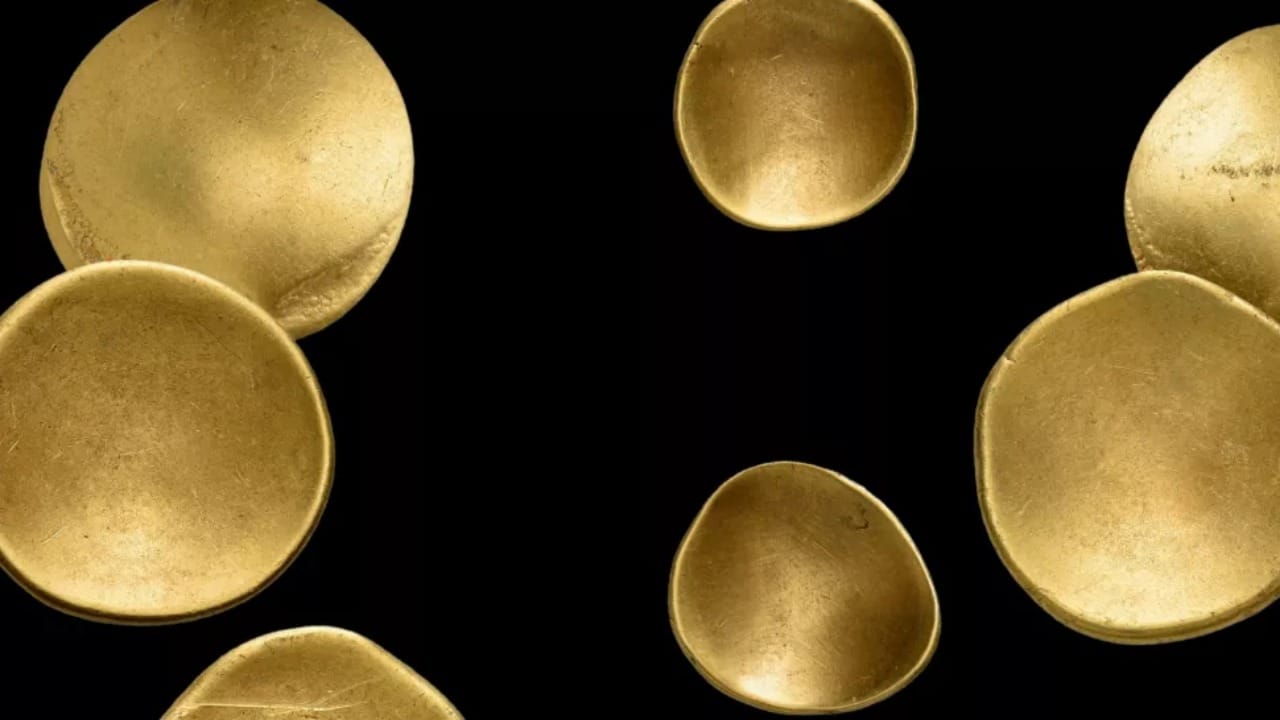

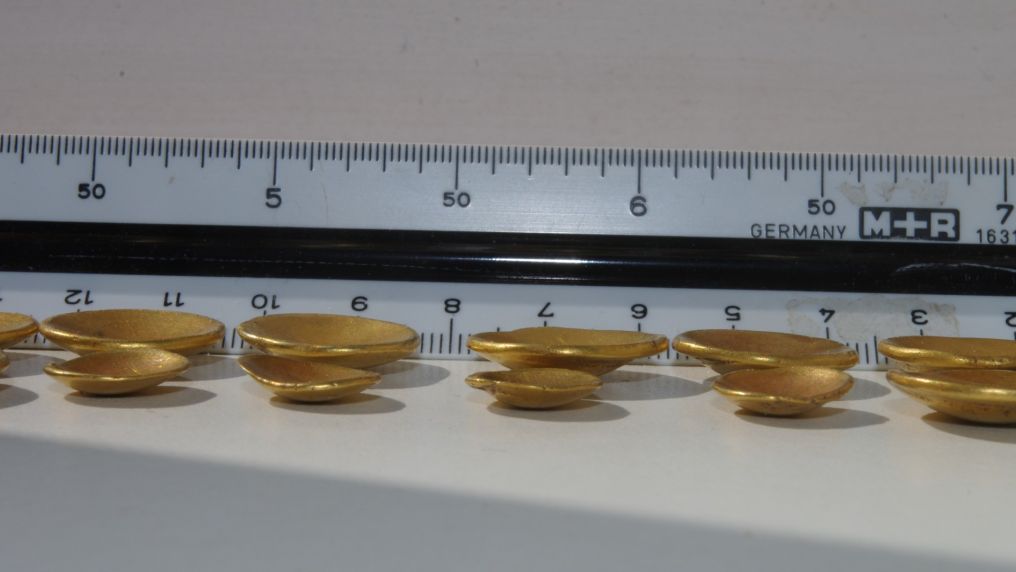

Since then, a total of 41 coins have been found. Most of them are gold, although there are a few silver and even copper specimens. Coins have an unusual bowl shape, they are also called “rainbow cups” and are firmly associated with the Celtic tradition of minting banknotes. And here begins the difficulty.

The fact is that the Celts never lived in what is now Brandenburg. And, accordingly, the Celtic gold has never been found there before (although in general, gold coin hoards were excavated). What is particularly interesting: this find is the second largest hoard of “rainbow cups” in history, and the largest was found in Britain, where the Celts, of course, lived.

After comparing the weight and size of the coins with those from other ancient hoards, experts have dated the coins to the period 125-30 B.C., the late Iron Age. The researchers link them to the Latenian archaeological culture. It correlates with the Celts and was widespread in Central and Southern Europe, as well as in Britain and Ireland in the V-I centuries B.C. (before the large-scale Roman conquests). By the first century B.C. (presumably the time of coinage), the Latenian culture occupied the territory of what is now England, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria, southern Germany and the Czech Republic. But not the land of Brandenburg: it remained to the north of the area of the culture.

The treasure was found on the site of an early German settlement belonging to the Jastorf archaeological culture. In general, the Jastorfian culture is a rather controversial topic in the professional archaeological community. The excavations of the settlements and burial grounds belonging to it were mainly carried out by German archaeologists, who also formed the theoretical justifications.

Thus, the discoverer of the Jastorf monuments, Gustav Schwantes, considered the nucleus (in his opinion, there was still a periphery) of this culture, besides the north of Germany, Jutland. German archaeology even formed the notion of “Jastorf civilization”. Schwantes’ Danish colleagues, however, strongly disagreed with this formulation of the question. As a result, there is still no common opinion about where the northern border of Jastorf culture was.

In any case, the land of Brandenburg is part of its core. One or two Celtic gold coins could have been an accident, the result of repeated exchanges between neighboring regions. But the 41 coins most likely indicate to us that there were major trade transactions between the Celts and the local population. These, we understand, could not have gone on unless there was peaceful cooperation between the peoples.

Therefore, the discovery of so many typical Celtic gold artifacts tells us first of all that we do not have a good enough idea of the economic relations between the different regions of Europe in the Late Iron Age. The fact is that historians always prefer written sources if they do not contradict archaeological findings. And we know the history of Europe at the beginning of the Roman conquests mainly from the testimonies of the Romans themselves.

Sometimes these sources are surprising: they forgot to list military units involved in the campaign (at least the commanders were always named), but spared no effort to describe the savagery, ferocity and bloodthirstiness of the peoples inhabiting the lands to be conquered. That is why the discovery of Celtic coins in clearly Germanic lands is so important: the more archaeological (material) evidence contradicts the Roman sources, the better we can understand the real history of Europe before the beginning of our era, not the one written by the victors.