The human factor is at the heart of scientific activity. (Photo: Matteo Farinella, CC BY-NC)

Even with scant memories of high school biology, most people remember the key cells of reproduction: the egg and the sperm. Perhaps you picture a multitude of sperm competing to be the first to reach the target.

For decades, scientific descriptions of human conception have reflected gender stereotypes: the egg has been assigned a passive role, while the sperm has been depicted as an energetic participant in the process.

Later studies showed that sperm were not strong enough to penetrate on their own, and that the process required mutual participation of cells. These discoveries coincided with cultural changes in ideas about gender equality.

You might be interested

-

“The first author was a woman. Her place is in the kitchen, not in scientific publications”: Gender bias in STEM publishing continues to limit opportunities for women.

-

The final choice remains with the egg – why is the myth of the “sperm competition” still popular?

-

Transferring tasks to artificial intelligence: a threat to independent thinking or the evolution of cognition?

Scientist Ludwik Fleck already in the 1930s characterized science as a cultural phenomenon. Since then, the understanding of the connection between scientific knowledge and current cultural attitudes has become more widespread.

Despite political controversies, society continues to expect impartiality from science—rationality free from the influence of cultural values.

When I began my neuroscience research in 2001, I shared these views. But biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling’s work Sexing the Body changed my perspective by demonstrating the interpenetration of cultural beliefs and scientific data. By the end of my doctorate, I began to view research through a socio-historical lens.

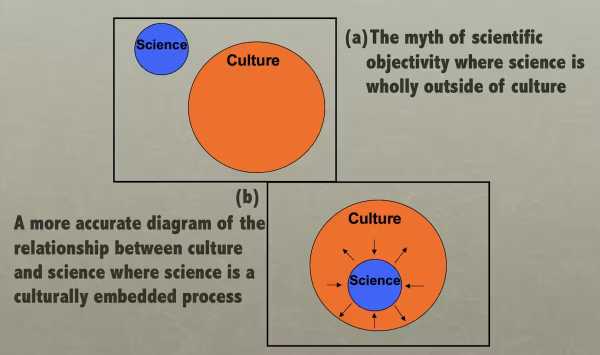

From the formulation of hypotheses to the interpretation of results, cultural attitudes permeate the scientific process. Is it ever possible to achieve absolute impartiality?

The Origins of the Concept of Scientific Impartiality

Only a few centuries ago, the Western academic system began to associate science with objectivity.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, European society began to move away from a religious and monarchical worldview. The strengthening of universities contributed to the transition from the authority of the church to rational thinking and scientific interpretation of nature. Academies became a platform for substantiating theories.

Previously, there was no clear division between the humanities and the natural sciences. Over time, disciplines began to be classified as subjective or objective, creating a hierarchy with rationality prioritized over emotion.

However, these binary categories turned out to be arbitrary and mutually reinforcing.

Alternative models of interaction between science and society. Scientific activity is a product of human culture.

Scientists are part of a sociocultural system. Like everyone else, they have family ties, political views, and cultural preferences. These aspects inevitably influence scientific work and the formation of “obvious” assumptions.

Research directions are determined by socially significant issues that correspond to dominant norms.

For example, in neuroscience, the central nervous system is seen as the control center, reflecting hierarchical thinking. In my research, I studied peripheral processes, although the dominant model prioritized the brain. This led me to think about the possibility of alternative approaches that emphasize the interaction of systems.

Every experiment contains hidden assumptions, including the definitions of concepts. Scientific research sometimes becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Billions are spent searching for gender differences, even though the categories of “male” and “female” themselves are rarely clearly defined. Accumulating evidence shows the ambiguity of these binary constructs. Similar problems arise in the study of race, sexuality, and other social categories.

Interpretation of results also depends on the cultural context, adding another layer of subjectivity.

Science in the absence of objectivity

Vaccinations, abortion, climate change – science has become an ideological battleground. The only common thread is the demand to separate science from politics, although each side accuses the other of bias.

Cultural biases in science are more noticeable when they conflict with personal beliefs.

Recent changes in the composition of the CDC's vaccine advisory board illustrate this dynamic, with accusations of bias coming from both sides of the political spectrum.

If it is impossible to eliminate subjectivity, how can reliable knowledge be created?

Recognizing the cultural conditioning of knowledge allows for the existence of multiple truths. However, this does not mean that all positions are equally valid; a democratic process of determining priority values is necessary.

Some scientists propose collaborative models similar to the Dutch “science shops” of the 1970s, where community groups participated in shaping the research agenda. Other practices involve engaging with marginalized communities.

RELATED MATERIALS

— Why are people inclined to believe conspiracy theories?

— Only 64% of Americans acknowledge evolution—what’s the reason?

— A medical journal has rejected a request to retract a controversial vaccine study.

True scientific objectivity is an illusion. Rejecting this myth opens a difficult path: humanity must consciously shape the values that determine scientific priorities. This requires agreeing on principles that may vary depending on the context and the stakeholders.

By using accumulated knowledge about the nature of scientific knowledge, society can build a more transparent dialogue between different positions.

This adapted article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. The original can be found here.

TAGS science

Sarah Giordano, Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, Kennesaw State University

Sarah Giordano is a feminist science studies scholar with a PhD in neuroscience from Emory University. A former ethics consultant for the CDC, her work focuses on science policy and critical scientific literacy. Her debut monograph, Labs of Our Own: Feminist Experiments with Science, will be published by Rutgers University Press in 2025.

Please confirm your public display name before commenting.

Please log in again to enter your name.

Exit Read more

Gender Stereotypes in Scientific Publishing: How Bias in STEM Disciplines Limits Women

The 'Sperm Race' Myth: Why Does Science Continue to Support It?

Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Human Thinking: Threats and Prospects

An Analysis of RFK Jr.'s False Claims About COVID Vaccines

Functional research: the basis of biology or risky experiments?

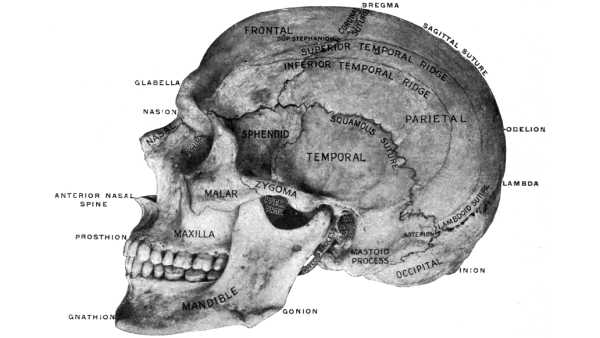

Racist Skull Studies in Victorian Science: A Historical Analysis LATEST NEWS

Ancient Egyptian coin dating back 12,200 years found in Jerusalem

Live Science is part of the international media group Future US Inc.

- About Us

- Contacts

- Terms of Use

- Confidentiality

- Cookies

- Availability

- Advertising

- Notifications

- Career

- Standards

- Suggest material

© Future US, Inc. 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type_opinion,type-crosspost,exclude-from-syndication,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com