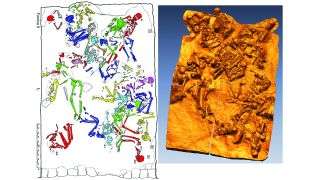

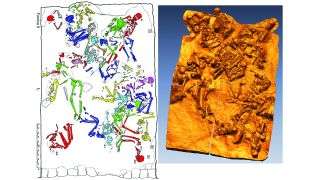

Excavation plan and 3D high-resolution laser scan record of the excavation in fornice 8.

The A.D. 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius, destroyer of Pompeii, also decimated the neighboring seaside town of Herculaneum. There, scores of people died more slowly than once thought, according to a new study.

When Vesuvius erupted, hundreds of Herculaneum residents fled to a nearby beach and perished while trying to escape; some experts previously concluded that the intense heat of melted rock, volcanic gases and ash, known as pyroclastic flows, vaporized the victims instantly.

However, new evidence gathered from the victims’ bones suggests that their fate was grimmer — and more lingering. Researchers estimated that temperatures of the pyroclastic flows were likely low enough that death wouldn’t have been mercifully instantaneous for people on the beach. Instead, the volcano’s victims would have suffocated to death on toxic fumes while trapped in oven-like boathouses, researchers recently reported.

Erupting volcanoes spew lava that can burn you, gas that can choke you and ash that can bury you. Pyroclastic flows — which do all three — can travel at speeds exceeding 50 mph (80 km/h) at temperatures reaching 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit (700 degrees Celsius), according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Between 1980 and 2012, archaeologists excavated and examined skeletons belonging to 340 individuals at the Herculaneum seafront — on the beach and inside 12 stone boathouses called fornici. A prior investigation of the remains, conducted in 2018, revealed unusual residue, thought to be sprayed body fluids, and star-shaped fractures on some of the skulls. Scientists concluded that the pyroclastic flows at Herculaneum were so hot — over 570 to 930 F (300 to 500 C) — that the victims’ blood had boiled and their heads had burst, Live Science previously reported.

But other researchers questioned this conclusion, and a recent analysis of the skeletons inside the fornici told a different story, said study co-author Tim Thompson, a professor of applied biological anthropology at Teesside University in Middlesbrough, United Kingdom.

Turning up the heat

Exposure to intense heat affects collagen inside bones, and changes the bones’ crystal structure, Thompson told Live Science. By examining the heat-induced changes in rib bones from 152 Herculaneum skeletons found inside the fornici, Thompson and his colleagues figured out the temperatures that caused the damage.

“We can take a piece of bone, we can run it through our equipment and we’re able to predict the temperature and intensity of burning that that skeleton has been exposed to, from the change in the crystal structure,” Thompson explained. “So we did that. And the results came back as being actually a relatively low-temperature heating event.”

In this case, “low-temperature” meant that the pyroclastic flows were no hotter than around 820 F (440 C) at most; meanwhile, cremation studies have previously shown that even temperatures of 1,800 F (1,000 C) aren’t high enough to vaporize tissue, according to the study.

In other words, while the pyroclastic flows at Herculaneum would have been hot enough to kill, they couldn’t have vaporized human flesh on contact, both inside the fornici or on the beach, the researchers reported.

What’s more, 92% of the bones that they examined had “good collagen preservation” — far more than the scientists expected to see in burned bones, Thompson said.

“Here, we had quite a significant amount of collagen left behind, which suggests to us that we had to look at a different mechanism that wasn’t direct burning and direct heat,” he said. Based on the condition of the bones, they likely baked in the heat, rather than burned, the scientists wrote in the study.

The fornici that temporarily sheltered people fleeing Herculaneum likely heated up like ovens once the roiling, heated mass of spewed volcanic rock and ash roared over them, trapping and smothering the people inside. Most of the bodies inside the fornici belonged to women and children, while the men and teenage boys perished on the beach, “trying to drag the boats out to escape,” Thompson said.

“Then, the pyroclastic flow comes down. And the thing about the fornici is, there is only one way in or out. Once that is covered with debris, what you end up with then is a little bit like an oven. You’ve got people trapped in there, there’s no air getting in and out, it’s dark, it’s full of dust and debris. Plus, these are stone structures, so they’re heating up from the heat from the pyroclastic flow that’s sitting on top,” he explained.

“That presented a new interpretation of how these people were dying,” Thompson said.

The findings were published online today (Jan. 23) in the journal Antiquity.

Sourse: www.livescience.com