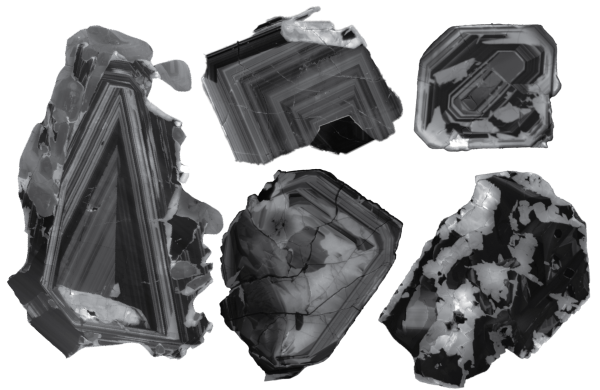

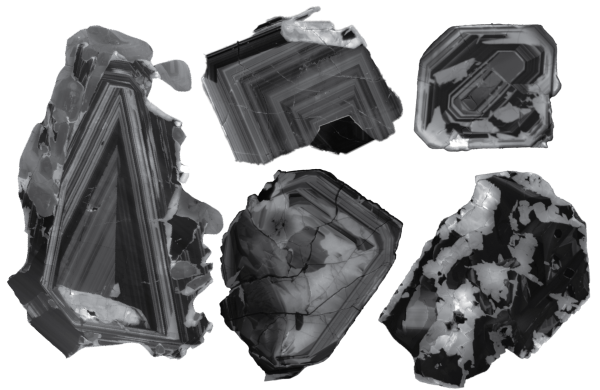

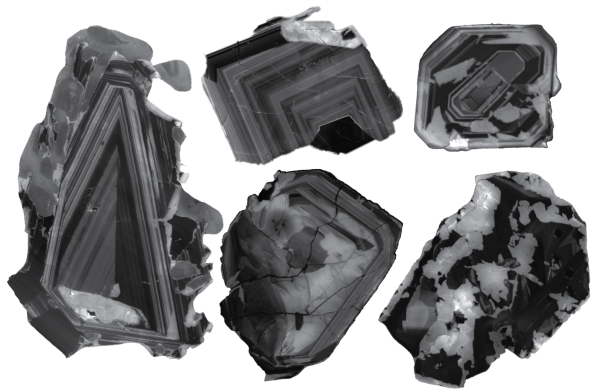

In this study, zircon crystals ranging in size from 0.1 to 1 mm were analyzed. Their isotopic analysis allowed the scientists to determine the age of carbonatite formation with a high degree of accuracy. (Image credit: Figure taken from: Droellner et al., (2025) Geological Magazine, Vol. 162, p. 33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100204. © The Author(s), 2025. Published by Cambridge University Press. License CC BY)

A newly discovered massive source of niobium, a metal essential for much of modern technology, appears to have formed when the supercontinent Rodinia broke apart about 830 million years ago, according to a new study.

Scientists in a study published September 2 in Geological Magazine reported that niobium-rich carbonatites, which may be one of the world's largest sources of the metal, are located deep in the Earth's mantle.

You may like

-

Rocks in Lake Superior bear witness to the aftermath of the giant collision that formed the supercontinent Rodinia.

-

The world's oldest rocks may shed light on how life emerged on Earth, and perhaps beyond.

-

A 400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes has been discovered under China.

Currently, 90% of the world's niobium reserves are extracted from a single mine in Brazil, with the remaining 10% coming from a Canadian mine. Understanding how, where, and when these enormous Australian deposits formed could help in the search for new ones, study co-author Maximilian Dröllner, a sedimentologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany, told Live Science.

Although small amounts of niobium can be found in various types of rocks, the quantities needed for economic and industrial extraction are primarily extracted from carbonatites – crystalline rocks composed primarily of igneous carbonate.

According to Dröllner, carbonatites are “a bit like a treasure chest,” as they contain important metal resources and rare earth elements locked within minerals. Their exact composition varies depending on where in the Earth's interior the magma originated.

Carbonatites are typically found only beneath the Earth's surface. But since the surface doesn't reveal what lies deep beneath, exploratory drilling and core extraction are the only ways to know for sure.

Two new high-grade niobium deposits in Australia's Eleron Province—Looney and Crean—were discovered during similar campaigns by mining companies WA1 Resources Ltd. in 2022 and Encounter Resources in 2023. The Looney deposit contains an estimated 200 million metric tons of niobium, while the smaller Crean deposit contains approximately 3.5 million metric tons.

The companies used diamond core drills to extract long cylindrical fragments of material from each site. Dröllner and his team then collected eight samples from three Luni cores and two samples from one Krin core.

You may like

-

Rocks in Lake Superior bear witness to the aftermath of the giant collision that formed the supercontinent Rodinia.

-

The world's oldest rocks may shed light on how life emerged on Earth, and perhaps beyond.

-

A 400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes has been discovered under China.

They took a thin section of each sample from areas that appeared to have the most diverse mix of minerals and textures, allowing the researchers to study the rock's geological history.

They then used a Selfrag machine to strike the remaining fragments with a series of lightning bolts. This caused the rocks to fracture along the boundaries of each mineral grain. They then placed these grains under a microscope and mass spectrometer to determine the age of the rocks.

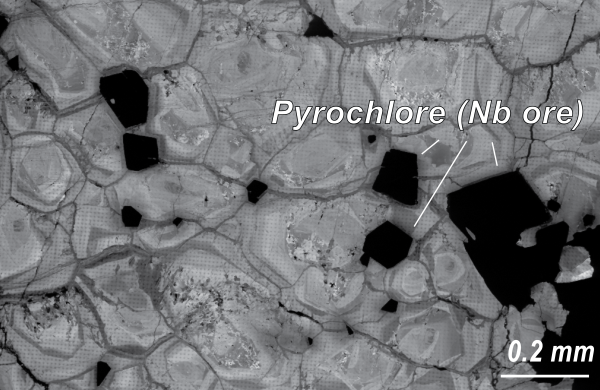

A close-up of pyrochlore crystals (black), the main niobium-bearing mineral, surrounded by apatite (pale gray) on the Luni carbonatite mineral map. Complex zoning within the apatite acts as a geological “time capsule.”

By looking at the ratios of different isotopes to their decay products, the researchers, partly funded by mining companies involved in the project, determined that the carbonatites, including the niobium mineralization, formed approximately 830–820 million years ago.

The analysis also revealed a “clear mantle signature,” Dröllner said, indicating that the carbonatite magma originated in the Earth's mantle, not the crust. Both deposits likely had the same source, with the internal system directing magma to each location branching off.

RELATED STORIES

—A huge deposit of rare earth elements has been discovered in the heart of an ancient Norwegian volcano.

A previously unseen ore containing a valuable rare earth element has been discovered in China.

— A volcano in Tanzania with the strangest and most fluid magma on Earth is going underground.

A group of scientists linked the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia to these deposits. When the supercontinent was pulled apart by tectonic plate movement, the Earth's crust at the resulting joints thinned, making it easier for the planet's interior to reach the surface. Helium isotope analysis showed that the Luni deposit was located in close proximity to the surface approximately 250 million years ago.

Anthony E. Williams-Jones, a professor of geology and geochemistry at McGill University in Montreal, who was not involved in the study, noted that this is a very high-quality study. However, he noted that since the researchers only studied cores, there is no information about the extent of the deposits and their appearance throughout the entire area.

Dröllner noted that further research is needed to create a 3D map of the deposits, which will ultimately allow for niobium extraction. However, a new understanding of how the Luni and Krin niobium deposits formed will help create a checklist for identifying other potential sites rich in this metal, he added.

Sophie Berdugo, Social Link Navigator, Live Science Contributor

Sophie is a UK-based staff writer for Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously covered research ranging from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in publications such as New Scientist, The Observer, and BBC Wildlife, and her freelance work for New Scientist was shortlisted for the 2025 Association of British Science Journalists' Newcomer of the Year Award. Before becoming a science journalist, she earned a PhD in evolutionary anthropology from Oxford University, where she spent four years studying why some chimpanzees are better tool users than others.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

Rocks in Lake Superior bear witness to the aftermath of the giant collision that formed the supercontinent Rodinia.

The world's oldest rocks may shed light on how life emerged on Earth, and perhaps beyond.

A 400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes has been discovered under China.

A hot spot under the Appalachians formed when Greenland broke away from North America, and it's moving toward New York.

Research raises important questions about Earth's 'oldest' impact crater

'Pulsing like a heartbeat': Rhythmic mantle plume rising from Ethiopia creates new ocean

Latest geology news

Narusawa Ice Cave: A lava tube filled with 10-foot-tall ice columns at the base of Mount Fuji.

A giant sand 'slug' is crawling across floodplains in Kazakhstan, but may soon freeze in place.

Scientists have discovered that the geology that supports the Himalayas is not what we thought.

Lugarema: The 'disappearing lake' in Northern Ireland that mysteriously dries up and refills within hours

Rocks in Lake Superior bear witness to the aftermath of the giant collision that formed the supercontinent Rodinia.

Three Whales Rock: 75-million-year-old giant rock formations in Thailand that look like they're floating on a sea of trees.

Latest news

A huge source of the rare earth metal niobium was brought to the surface when the supercontinent broke apart.

Watch the sky! This October, you'll be able to see two bright comets on the same night during a meteor shower.

Saturn will be at its brightest and largest on September 21—here's how to see it.

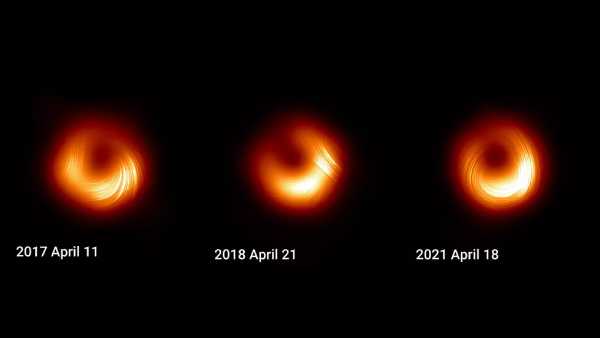

The first black hole ever directly photographed has changed dramatically in just four years, according to a new study.

CDC committee votes to change measles vaccination recommendations for young children

Goodbye, computer mouse? Scientists say innovative new designs can reduce the risk of wrist injuries.

LATEST ARTICLES

Goodbye, computer mouse? Scientists say new, innovative designs can reduce the risk of wrist injuries.

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com