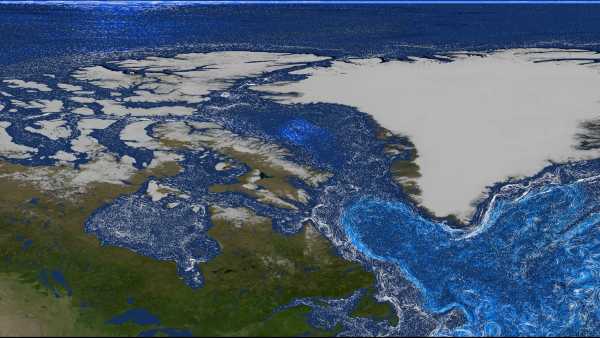

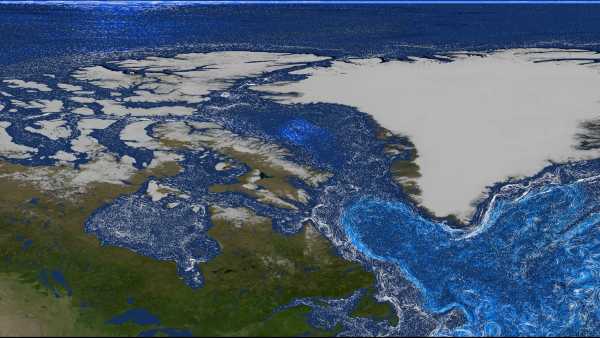

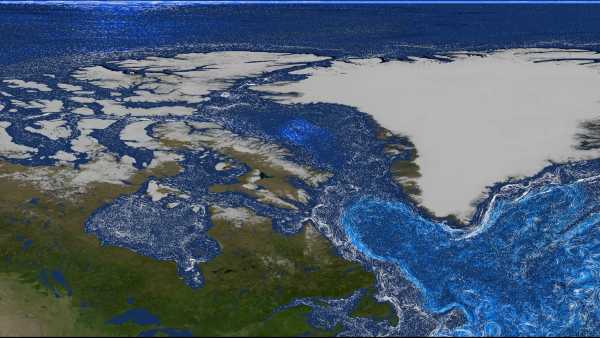

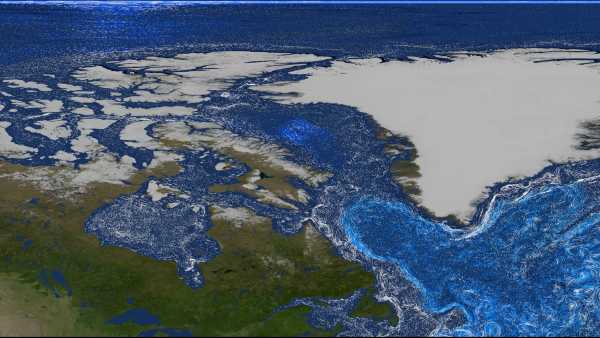

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is a system of currents located south of Greenland. (Image credit: NASA Scientific Visualization Studio)

A new analysis of shellfish shells suggests that a vast system of rotating ocean currents in the North Atlantic is behaving extremely strangely, possibly because it is approaching a tipping point.

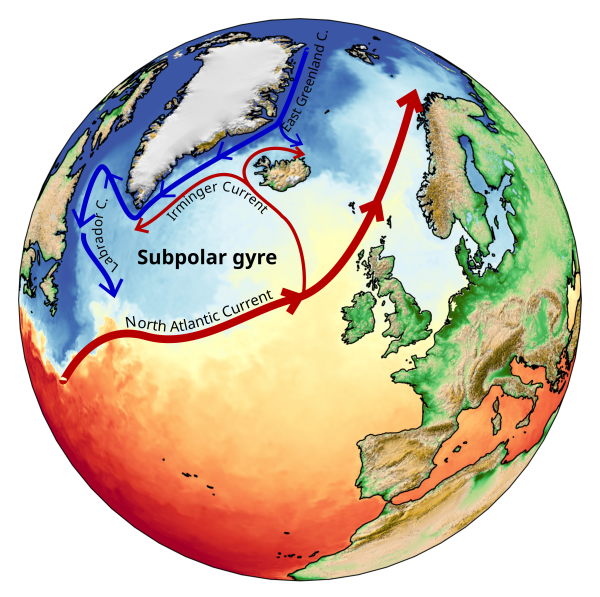

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre plays a key role in transporting heat to the Northern Hemisphere and is part of a much larger network of ocean currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). However, new data suggest that the subpolar gyre has been losing stability since the 1950s, meaning its circulation could weaken significantly in the coming decades, researchers report in a study published today (October 3) in the journal Science Advances.

You may like

-

According to a new study, 96% of the world's oceans will experience extreme heat in 2023.

-

Even a small slowdown in key Atlantic currents poses a “massive risk” to tropical forests.

-

Antarctic sea ice collapse linked to mysterious surge in ocean salt levels

Currents in the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre are also part of the AMOC, but the subpolar gyre can destabilize and cross tipping points independently of the AMOC.

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is part of the AMOC, but it could reach a point of no return regardless of the massive network of currents. The climate impacts on Europe, in particular, would be similar to those that would occur if the AMOC were to collapse, although they could be less intense because the AMOC is much larger, Arellano Nava stated. However, “even if the impacts are not as catastrophic as if the AMOC were to collapse, the weakening of the subpolar gyre could lead to significant climate change,” she warned.

Previous research suggests that the AMOC may collapse in the near future as its main engine—the cascade of dense water flowing from the surface of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans to the seafloor—fails. This cascade, which until now consisted of extremely cold and salty water, is being diluted by meltwater and warmed by rising global temperatures, causing the water in some places to become insufficiently dense to sink properly. (Cold, salty water is denser than warm, less salty water.)

A similar fate awaits the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre, which also depends on surface water sinking to the ocean floor. A cascade of dense water at the center of the gyre maintains the rotational currents, said Arellano Nava. However, the system is also partially driven by wind, so a complete collapse is unlikely, she added.

The North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre is a branch of the AMOC, so the collapse of the AMOC inevitably entails a sharp weakening of the gyre. Conversely, a weakening of the subpolar gyre does not automatically imply a collapse of the AMOC, Arellano Nava noted.

“The subpolar gyre can weaken sharply without destroying the AMOC,” she explained. “This is precisely what happened during the transition to the Little Ice Age, which occurred in the 13th and 14th centuries.”

The Little Ice Age, which lasted from approximately 1250 to the late 19th century, is one of the coldest periods in the history of the Northern Hemisphere since the end of the last ice age. Average temperatures dropped by approximately 2 degrees Celsius, causing rivers and harbors across Europe and North America to freeze over in winter, triggering agricultural crises and essentially plunging medieval society into chaos, according to The New Yorker. While factors such as volcanic eruptions and declining solar activity contributed to the onset of the Little Ice Age, the North Atlantic Subpolar Circulation is believed to have played a significant role in its intensification.

Due to climate change, conditions now differ dramatically from those of the 13th century, so scientists don't know whether another Little Ice Age is possible, Arellano Nava said. However, it illustrates some of the climate consequences we may face.

You may like

-

According to a new study, 96% of the world's oceans will experience extreme heat in 2023.

-

Even a small slowdown in key Atlantic currents poses a “massive risk” to tropical forests.

-

Antarctic sea ice collapse linked to mysterious surge in ocean salt levels

Clues in the shellfish

For the new study, Arellano Nava and her colleagues analyzed existing datasets obtained from the shells of two species of North Atlantic clams: Arctica islandica and Glycymeris glycymeris. The clams record information about the ocean in their shells as they grow; for example, they absorb various forms of elements such as oxygen, which can provide researchers with clues about ocean processes over time.

“Thanks to the mollusc data, we can precisely date each layer,” Arellano Nava said. “They're like tree rings in the ocean.”

A close-up of the growth stripes on the shell of a blenny clam (Glycymeris glycymeris).

Researchers compiled 25 datasets to create a highly accurate picture of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre over the past 150 years. They discovered two strong instability signals. The latter is ongoing and indicates that the subpolar gyre is approaching a tipping point as a result of global warming, confirming previous observations and studies, Arellano Nava reported.

But another signal came as a complete surprise, she said. Data obtained using shellfish showed that the subpolar gyre was unstable for several years leading up to a regime shift in the North Atlantic in the 1920s. This previously described event was characterized by a strengthening of currents in the gyre. The instability of the subpolar gyre likely triggered the regime shift in the 1920s, and the chronology of events suggests that the period of instability may have been related to the recovery of the subpolar gyre after its collapse during the Little Ice Age, Arellano Nava said.

“At some point it had to regain strength, but we don't have definitive evidence of that because we haven't studied those mechanisms,” she said.

Whether or not the instability of the early 20th century was actually a signal that the subpolar circulation was returning to its full strength, the coincidence of the signal in the shellfish data and the change in the North Atlantic regime in the 1920s shows that the results are reliable, Arellano Nava said.

“If you see a loss of stability followed by a rapid change, then you can be confident that these are early warning signs of a dramatic change,” she said.

RELATED STORIES

“We no longer consider it unlikely”: the collapse of a key Atlantic current could have catastrophic consequences, says oceanographer Stefan Rahmstorf.

— Research has shown that the collapse of key Atlantic currents could be prevented thanks to a newly discovered backup system.

— The mystery of the cold spot in the Atlantic Ocean has finally been solved.

However, another expert expressed less confidence. “These datasets are very useful because they are very well dated and allow us to analyze climate change year by year,” David Thornalley, a professor of oceanography and climate science at University College London who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

However, the analysis did not directly link the observed patterns in the shellfish data to ocean physics and did not provide compelling evidence of a change in the subpolar gyre's operating mode, Thornalley said. “I'm skeptical of that interpretation,” he said.

Regarding the ongoing destabilization of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre, Arellano Nava said she and her team have begun mapping the potential climate trajectories this could reveal.

“We don't know exactly what the tipping point will be,” she said. “It could be the AMOC… but we may be seeing a weakening of the subpolar gyre, and that's certainly concerning.”

Sasha Pare, Social Link Navigation, Staff Writer

Sasha is a staff writer for Live Science based in the UK. She holds a BA in Biology from the University of Southampton in England and an MA in Science Communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and on the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, baking bread, and browsing thrift stores.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

According to a new study, 96% of the world's oceans will experience extreme heat in 2023.

Even a small slowdown in key Atlantic currents poses a “massive risk” to tropical forests.

Antarctic sea ice collapse linked to mysterious surge in ocean salt levels

Drastic changes happening in Antarctica will 'affect the world for generations to come'

Scientists have detected changes in the polar vortex that are plunging parts of the US into a deep freeze.

Strong northeasterly winds along the US East Coast are becoming more intense as global warming continues, according to a study.

Latest news about rivers and oceans

A Chinese submersible is exploring previously unknown giant craters on the Pacific Ocean floor – and they're teeming with life.

Rare milky plumes create stunning swirls in the world's largest 'carbonated lake'

Rocket-shaped jellyfish, majestic Komodo dragons, and a harrowing whale rescue—meet the stunning finalists of the 2025 Marine Photographer of the Year competition.

Data from the North Sea shows that “rogue waves” can reach heights of 65 feet, but they are not “anomalous events.”

Even a small slowdown in key Atlantic currents poses a “massive risk” to tropical forests.

According to a new study, 96% of the world's oceans will experience extreme heat in 2023.

Latest news

Harvest Moon 2025: Watch a rare supermoon rise in October against a backdrop of shooting stars

A vast system of rotating ocean currents in the North Atlantic is behaving strangely – and may be approaching a tipping point.

Anthropologists prepare “ant yogurt” using an ancient recipe and serve it as an “ant dish” in a Michelin-starred restaurant.

Scientists transplant a kidney from blood type A to the universal blood type O and implant it into a brain-dead recipient.

A leading group of obstetricians and gynecologists recommends against using cannabis during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Divers have recovered more than 1,000 gold and silver coins from the Treasure Fleet, a ship that sank in Florida in 1715.

LATEST ARTICLES

1A massive system of rotating ocean currents in the North Atlantic is behaving strangely – and may be approaching a tipping point.

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com