Is it true that every fig contains a sacrificed wasp? (Image courtesy of Studio4 via Getty Images)

If you love figs, you've probably heard a disturbing legend about them: every fig hides a wasp, because these insects must crawl inside and die for the fruit to grow. But are there really wasps in the figs we eat, or is this just a myth?

The answer is somewhere in the middle. Wasps do play an important role in the life cycle of many fig species, but most supermarket figs are likely free of insect infestation.

You may like

-

Why do cats and dogs eat grass?

-

This week's science news: The world's oldest mummy and an ant mating with clones of a distant species

-

Sticky liquid in 2,500-year-old bronze vessels finally identified, ending 70-year debate

“Fig trees and fig wasps are a prime example of mutualism,” Charlotte Jander, a plant ecology and evolution researcher at Uppsala University in Sweden, told Live Science in an email. “Other examples of mutualism include trees and mycorrhizal fungi, which help trees absorb nutrients, animals and their gut microbiota, and flowering plants and pollinators in general.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Life's Little Mysteries, to receive the latest detective stories before they hit the web.

In the case of the fig tree and the fig wasp, the fruit is pollinated and the wasp reproduces, resulting in mutualism. However, this relationship is quite complex.

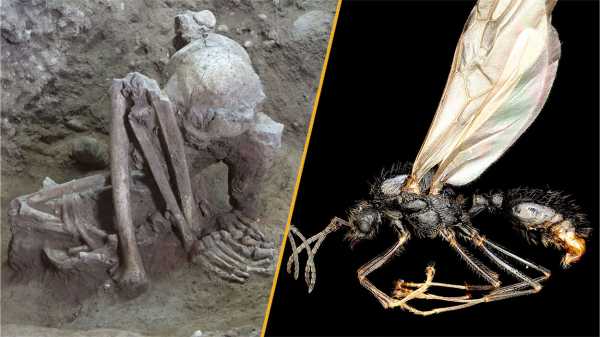

What we think of as the “fruit” of a fig is actually a hollow structure called a syconium, filled with tiny flowers. Typically, when a female fig wasp crawls into the syconium of a female fig, she releases pollen, which the plant needs to produce and mature seeds. The opening the wasp enters is very small, and in doing so, she can lose her wings and antennae and even die inside the fig.

Therefore, it is possible that some fig species may contain dead fig wasps inside.

But this doesn't necessarily mean there are wasps in the figs we eat. Not all fig species require pollination to ripen. People eat figs of the species Ficus carica, which has several parthenocarpic varieties, meaning they can produce ripe fruit without pollination, and therefore without fig wasps.

“Most figs we eat in the U.S. don't have wasps inside them,” Carlos Machado, a biology professor at the University of Maryland, told Live Science in an email.

A female wasp penetrates a fig fruit. Fig wasps cannot sting humans, and they are much smaller than the wasps that do.

According to Jander, the Mission and Brown Turkey figs are two common fig varieties that don't require wasp pollination to ripen and produce seeds. However, this isn't true for all edible figs: Smyrna figs, Calimyrna figs, and wild figs throughout the Mediterranean are pollinated by wasps.

You may like

-

Why do cats and dogs eat grass?

-

This week's science news: The world's oldest mummy and an ant mating with clones of a distant species

-

Sticky liquid in 2,500-year-old bronze vessels finally identified, ending 70-year debate

“Most wild figs require pollination to ripen,” Machado explained. This means there could be a tiny wasp inside these figs, but it's still not a guarantee.

Just because a wasp was once inside a fig doesn't mean it's still there when the fig is eaten. Ficus carcia synconia have a large enough opening that a fig wasp can sometimes escape by entering. If a wasp dies inside, its body is usually crushed and decomposed as the fig ripens, Jander said.

“Even if there were remains of the original pollinator, you probably wouldn't see them,” Jander explained. The crunchy texture likely comes from the plant's seeds, not the remains of a wasp.

Life cycle of the fig wasp

Although wasps sometimes die inside fig trees, these fruits are actually an integral part of their reproductive cycle. Just as most fig species require wasp pollination to produce new fruit, fig wasps would be unable to reproduce without the help of fig trees.

When a female wasp crawls into the syconium of a female tree (the same figs we eat), she only pollinates it because the flowers inside are too long for her to lay eggs. But if she crawls into the syconium of a male tree (called caprifigs and not usually eaten by humans), she will begin laying eggs.

There, the eggs hatch into larvae that develop into young wasps, which mate while still inside the fruit. Male wasps typically die inside the fruit after mating, although they help gnaw a tunnel to allow the females to escape, sometimes even offering themselves as bait for predatory ants that may be waiting outside. Eventually, the fertilized female wasps fly out in search of a new fruit to lay their eggs, carrying pollen from the old fruit with them.

RELATED SECRETS

— Are kale, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts really the same plant?

—Why are the seeds of strawberries located on the outside?

—Why are bananas berries but strawberries aren’t?

According to Jander, there are more than 850 species of fig, and each can only be pollinated by a specific species of fig wasp. The relationship between these plants and animals developed millions of years ago, and both Machado and Jander note its importance. As a keystone species—an organism on which many other plants and animals in an ecosystem depend—the fig and its relationship with wasps continues to be of great interest to researchers.

“There are other types of mutualisms between plants and pollinators in nature, but the mutualism between the fig and the wasp is probably the most diverse and most important of all,” Machado said.

TOPICS: Life's Little Secrets

Marilyn Perkins, Content Manager

Marilyn Perkins is a content manager at Live Science. She is a science writer and illustrator based in Los Angeles, California. She earned a master's degree in science writing from Johns Hopkins University and a bachelor's degree in neuroscience from Pomona College. Her work has appeared in publications such as New Scientist, the Journal of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Penn Today. In 2024, she was awarded the National Science Writers Association's Excellence in Institutional Writing Award in the short-form category.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

Why do cats and dogs eat grass?

This week's science news: The world's oldest mummy and an ant mating with clones of a distant species

Sticky liquid in 2,500-year-old bronze vessels finally identified, ending 70-year debate

'Your concerns are well-founded': How human activity has increased the risk of tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease

'Almost like science fiction': European ant is the first known animal to clone members of another species.

Spiders keep fireflies as glowing captives, which attract more prey to their webs.

Latest news about plants

Cairo Fossil Forest: The oldest forest in North America, with trees 385 million years old.

'This needs to be done quickly': Scientists rush to cryopreserve endangered tree before it disappears

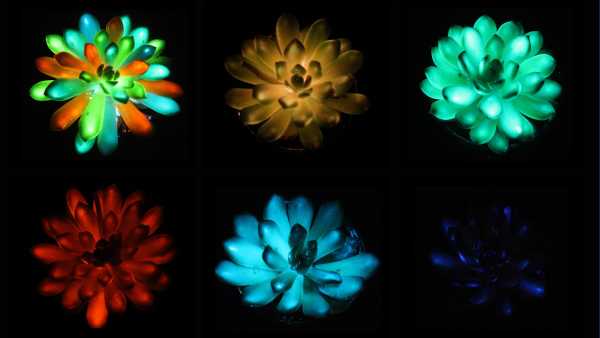

Chinese scientists have created multi-colored succulents that glow in the dark and are charged by sunlight.

Plants have a secret second set of roots located deep underground that scientists didn't know about.

Kilimanjaro's Giant Senecios: Strange Plants That Thrive on Africa's Highest Mountain

'This shouldn't be published': Scientists question study claiming trees 'talk' before solar eclipses

Latest features

History of Science: Rosetta Stone Deciphered, Opening Window into Ancient Egyptian Civilization – September 27, 1822

Science Story: DART, humanity's first asteroid deflection mission, hits space rock in the face – September 26, 2022

Doctors restored a man's vision by removing a tooth and implanting it in his eye.

Why do medicines taste bad?

Paralvinella hessleri: A yellow worm that lives in acid and fights poison with venom.

Why does Pluto have such a strange orbit?

LATEST ARTICLES

Why OpenAI's Anti-AI Hallucination Solution Will Kill ChatGPT Tomorrow

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-llm,van-disable-newsletter,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com