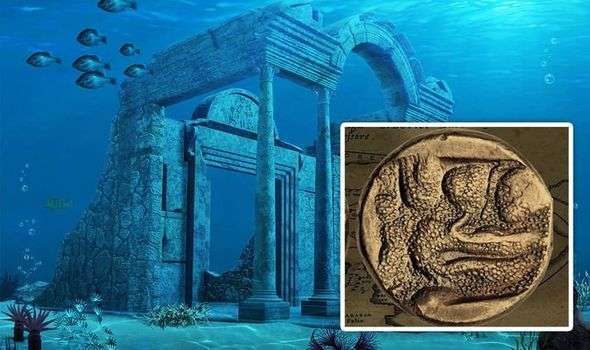

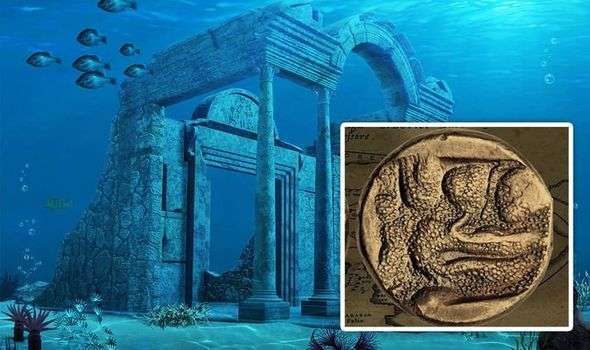

THE ATLANTIS mystery may have finally been unravelled by an author and researcher after analysing a 2,400-year-old coin discovery that was said to match the description given by Plato.

The mythical island was first described by the Greek writer in his texts ‘Timaeus’ and ‘Critias,’ said to be an antagonist naval power that besieged “Ancient Athens”. In the story, Athens repels the Atlantean attack unlike any other nation of the known world, supposedly giving testament to the superiority of ancient Greece. The legend concludes with Atlantis falling out of favour with the deities and submerging into what is believed to be the Atlantic Ocean.

Trending

But, Christos Djonis, the author of ‘Atlantis Revealed,’ has an alternative theory and it’s thanks to a coin discovered more than 20 years ago.

The researcher believes the story of Atlantis was a Greek legend passed down, like the Palace of Knossos and the city of Troy – but he also thinks its inspiration may have been taken from the Americas.

Speaking in a YouTube video on the Ancient Origins channel, he said last month: “Many scholars and researchers also show that proper translation of Plato’s text places Atlantis in the Mediterranean and not in the Atlantic or some other exotic location.

“It is conceivable to accept that the ancient Greeks, around the fourth century BC, knew of the American continent across the Atlantic.

“Roughly 20 years ago, in 1996, Mark McMenamin, a professor of geology, discovered and interpreted a series of enigmatic markings on the reverse side of a Carthaginian gold coin minted in 350BC as an ancient map of the world.

“In the centre of this world map, there is a clear depiction of the Mediterranean Basin, an image to the right of it is interpreted to represent Asia, while the image to the left is interpreted to represent the American continent.

“Professor McMenamin also found that all known specimens of this type of coin formed the same type of world map.”

Mr Djonis went on to reveal how there is further evidence of this theory.

He added: “What is most interesting about the find is that this particular coin was minted within the same decade when Plato unveiled the story of Atlantis and revealed that there was a large continent across from the Pillars of Hercules.

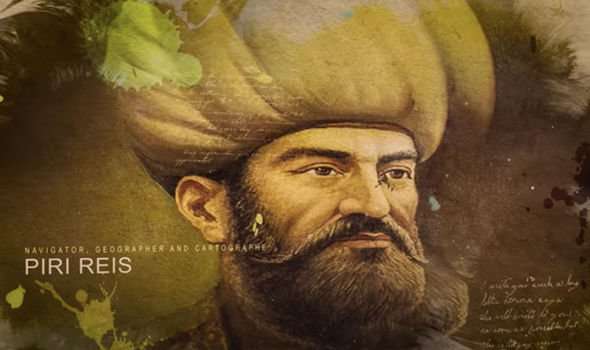

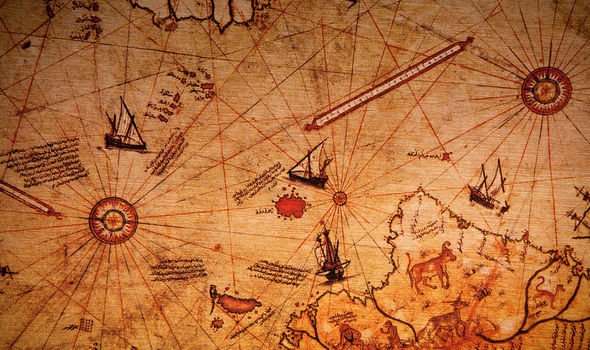

“The Piri Reis World Map, named after its maker – a Turkish Admiral and renowned cartographer – drawn in 1513, nearly two decades after the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, depicts the west coast of Africa, Europe, as well as the entire American continent on the Atlantic site.

“According to Piri Reis, however, his controversial map was based on several over charts, many dating back as early as the fourth century BC.

“While it does not come close to a satellite image, he still depicts the continents on both sides of the Atlantic, although it does show the Horn of Africa turning sharply eastwards, almost at a 90-degree angle.

“Some speculate that the horizontal body of that land could be that of Antarctica, causing controversy, since it was not discovered until 300 years later.”

DONT MISS

End of the world: How archaeologist discovered ‘real Maayan doomsday’ [VIDEO]

Mayan DISCOVERY: How find in ancient city ‘reveals creation story’ [CLAIM]

Egypt: How ‘greatest archaeological find of all time’ stunned expert [REVEALED]

If the map was borrowed from other ancient interpretations, then it would reinforce the suggestion that Plato was aware of the American continent.

But, Mr Djonis says there is further evidence that the ancient Greeks were more aware of the world around them than previously thought.

He added: “Additional clues, though, not only suggest that the ancient Greeks knew of North America across the Atlantic, but as it appears, they were also familiar with the region around the Arctic Circle – in essence, the broken bridge that connects northern Europe to North America.

“They called this land Hyperborea, a Greek word that means ‘extremely north’.

“While undoubtedly sceptics would dismiss this suggestion, interestingly, the Greeks believed that Hyperborea was an unspoiled territory so far north from Greece, where the Sun never set.

“Of course, the only place due north where the sun continuously shines, at least six months out of a year, is the region above the Arctic circle, a territory obviously not easily accessible, especially during the winter months.

“Coincidentally, the poet Pindar wrote that ‘neither by ship nor on foot would you find the marvellous road to the assembly of the Hyperboreans,’ a statement that further corroborates the inaccessibility of this region.”

Mr Djonis went on to explain how the ancient Greeks were renowned for telling stories of real places wrapped in mythical elements.

He continued: “Such, among others, was the Palace of Knossos, the city of Troy and Mount Olympus, what about Hyperborea though? Is it possible that the Greeks managed to navigate so far north, or was that knowledge passed down to them from others, such as the Minoans perhaps?

“If, according to historians, the Bronze Age Minoans 4,000 years ago were often travelling as far as Scotland and the Orkney Islands to trade goods, is it inconceivable to assume that over time they may have eventually reached Greenland, only a couple of short island stops away?

“If those ancient navigators managed to reach Greenland via island hopping, is it possible then to assume that they could have gone a bit further and ultimately reached North America, which in essence, is just around the corner?

“If not, where did thousands of tonnes of copper from the region around the Great Lakes disappear to during the Bronze Age? Mor importantly, how did spices, plants and insects indigenous only to America find themselves in Santorini around the period of 1600BC?

“An excavation in the ancient city of Akrotiri, on the island of Santorini, revealed that a tobacco beetle, an insect indigenous to America at the time, was found buried under the volcanic ash of the 1600BC eruption, but tobacco was not introduced to Europeans until around 1518AD, as history claims.”

While present-day philologists and classicists agree on the story’s fictional character, there is still debate on what served as its inspiration.

As for instance with the story of Gyges, Plato is known to have freely borrowed some of his allegories and metaphors from older traditions.

This led a number of scholars to investigate possible inspiration of Atlantis from Egyptian records of the Thera eruption, the Sea Peoples invasion, or the Trojan War.

Others have rejected this chain of tradition as implausible and insist that Plato created an entirely fictional nation as his example, drawing loose inspiration from contemporary events such as the failed Athenian invasion of Sicily in 415 – 413BC or the destruction of Helike in 373BC.

Sourse: www.express.co.uk