AN END OF THE WORLD-threatening event would no doubt see the majority of humanity wiped from the face of the Earth, but in the slim chance that some do survive, a “Noah’s Ark” of bacteria could give the opportunity to repopulate life.

In 2019, Express.co.uk reported that the Norwegian government had funded a secret “doomsday vault” – a secure seed bank on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, near Longyearbyen, approximately 810 miles from the North Pole. The bank will preserve a wide variety of plant seeds that are duplicate samples, or “spare” copies held in gene banks worldwide in an attempt to ensure against the loss of seeds during the large-scale regional or global crisis. But seeds aren’t the only part of nature that would be critical to restarting life and now scientists have begun to consider the benefits of building a similar vault for important microbes, described as “a Noah’s Ark for germs” in reports.

Trending

Dr Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, a microbiologist at Rutgers University, was inspired by the seed storage idea and so the idea of preserving microbes seemed like a natural development.

Speaking to Digital Trends last week, she said: “It was so obvious, and I became very interested in the idea of doing something like that for the microbiome.”

Microbiotas are all microorganisms — including bacteria, viruses, and fungi — found in a particular environment, like the skin or gastrointestinal tract.

The microbiome refers to those microorganisms and their genes.

Many factors influence the mix of these microbes inside the gut, including both hereditary and environmental components.

Research about how microbiota influence human health is still relatively new, but they are thought to play a vital role in the immune system, enzyme synthesis, and digestion of complex carbohydrates.

But Dr Dominguez-Bello fears that as research into this area develops, vital data from indigenous populations could be missed.

She added: “By the time we know better– if we don’t preserve now, we won’t have it.”

After contacting the researchers involved in the Svalbard project, Dr Dominguez-Bello started assembling scientists in her own field to look at the potential of creating a microbiota vault.

In mid-June of this year, a feasibility study from two independent agencies, EvalueScience and Advocacy, found the proposal to be “of high significance and potential”.

There already exist a number of microorganism collections all over the world, including the American Gut Project, Asia Microbiota Bank, and the Million Microbiome of Humans Project.

But, Dr Dominguez-Bello wants to convince them to hand over samples for back-up storage.

The plan is to partner with universities in various countries to teach local scientists about the microbiome, why such collections are needed, and how to collect and preserve samples.

She added: “The local collections are extremely important because the local collections are the live collections.

“This is more than microbiology. This is also anthropology and ethics.”

Two potential methods for the vault are cryopreservation, with liquid nitrogen, and lyophilisation, or freeze-drying.

While liquid nitrogen is the gold standard, Dr Dominguez-Bello said freeze-dried samples wouldn’t require electricity, if they were stored in a cold enough area.

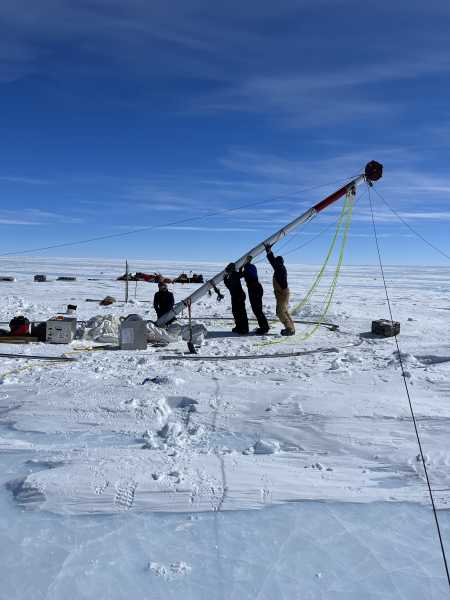

The microbiota vault’s organisers are considering either Switzerland or Norway or potentially both locations.

Unlike with a vault full of seeds, there are ethical and privacy concerns that come along with collecting and retaining human samples.

Laws in both the countries where collections are stored and procured may vary.

For example, some countries – including Switzerland and Norway – are part of the Nagoya Protocol, an international agreement that attempts to equitably share the benefits that come from genetic research.

Whether microbiota samples fall under this agreement is still under debate.

Regardless, Dr Dominguez-Bello believes any institution that hopes to profit from these microbiota samples – for example, by creating a new probiotic – has a responsibility to the communities that donated relevant samples.

She said: “There is an ethical obligation with the people that were the source of those bacteria.

“You do have to do something for the good, for the well-being of their community as a whole.”

Sourse: www.express.co.uk