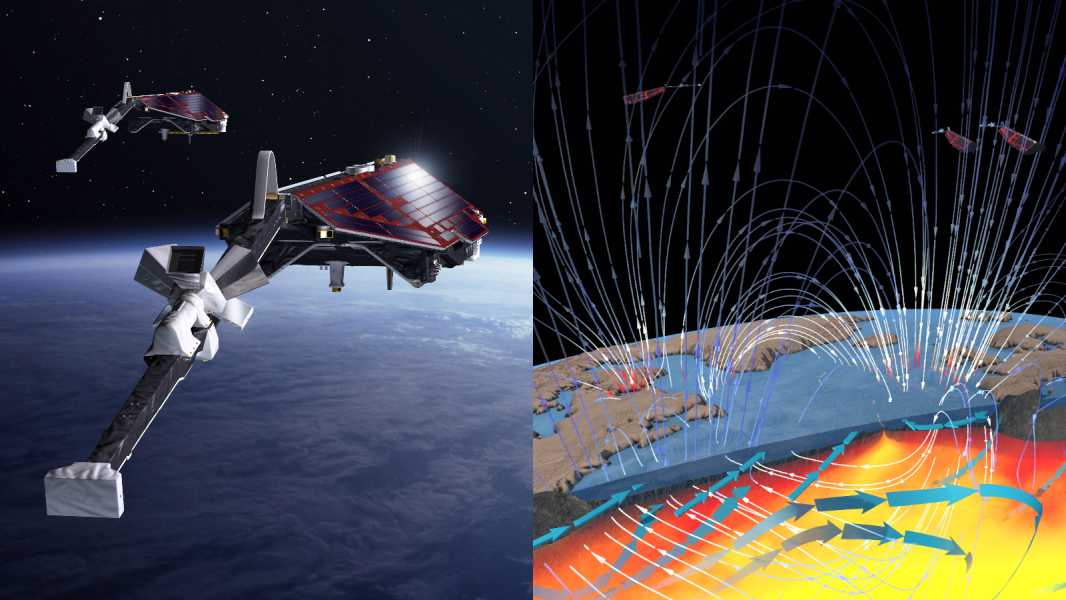

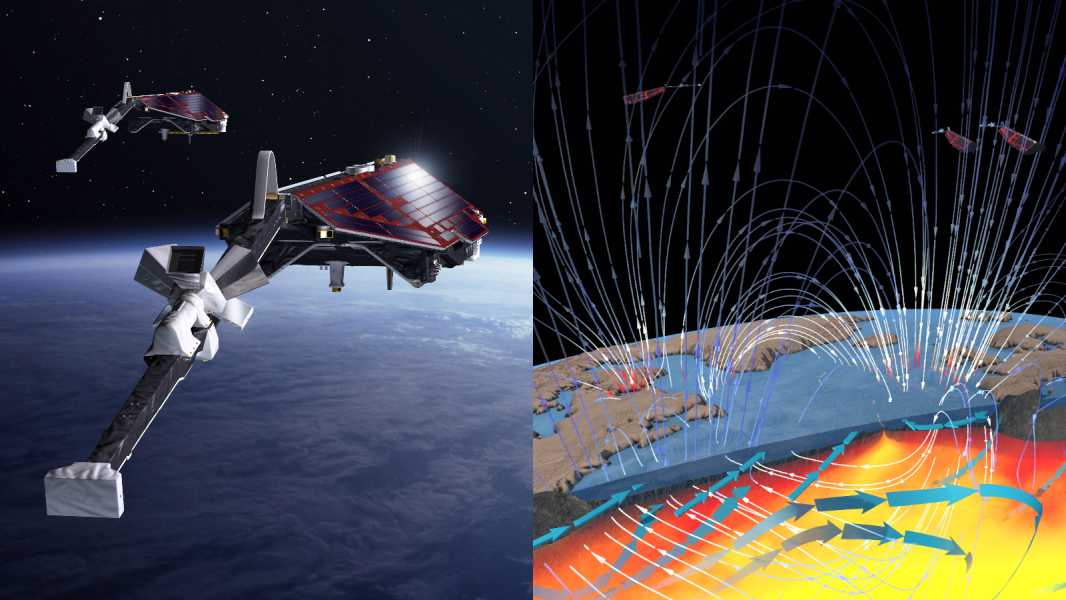

Satellites orbiting the Earth have detected subtle magnetic signals caused by ocean tides. (Image courtesy of the European Space Agency)

Researchers have studied in detail the magnetic signals associated with the Earth's ocean tides.

These faint signals, which can be picked up by some satellites in very low orbits, may contain clues about the location of magma beneath the seafloor, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

When seawater oscillates under the influence of our planet’s magnetic field, it creates tiny electric currents, which in turn generate magnetic signals that can be detected from space. In a new study published online December 2, 2024, in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, scientists have decoded these signals using data from ESA’s current Swarm mission, a group of three satellites measuring Earth’s magnetic field.

“These are some of the weakest signals recorded by the Swarm mission to date,” said lead study author Alexander Greiver, a geophysicist and senior lecturer at the University of Cologne in Germany.

The Earth's magnetic field is formed by the swirling motion of electrically charged molten iron in the planet's outer core. Heat flows and the Earth's rotation help move this liquid iron. The core's motion creates a huge bipolar shell extending into space that protects us from cosmic radiation and charged particles emitted by the sun.

Swarm was launched in 2013 and has been collecting data on Earth's magnetic field ever since. However, clear signals created by ocean tides are difficult to obtain because they are so weak that they almost never break through the widespread “noise” in space, the statement said.

In the late 2010s, several factors came together to allow Swarm to capture the magnetic signatures of ocean tides with unprecedented clarity. One of these factors was a significant decrease in solar activity, and another was the proximity of the Swarm satellites to Earth.

“The data is especially good because it was collected during solar minimum, when there was less interference from space weather,” Graver added.

The sun follows a roughly 11-year cycle that determines the level of activity on its surface. During solar maximum, the sun emits powerful waves of electromagnetic radiation and charged particles that obscure magnetic signal measurements from Earth. Activity decreases during solar minimum, making it easier for satellites to detect these signals.

ESA originally planned to end the Swarm mission in 2017, but its valuable results prompted the agency to extend the project. Over the years, the satellites’ orbits have moved closer to Earth, allowing their instruments to pick up faint signals that they couldn’t detect in their original, higher orbits.

“That’s one of the benefits of long-duration missions that go beyond the originally planned duration,” said Anja Strömme, Swarm mission manager at ESA. “You can do science that wasn’t originally planned.”

The new study demonstrates that satellites can explore the depths of Earth's oceans and extract valuable information, Strömme said.

Swarm could remain active until 2030, when the next solar minimum occurs. Scientists hope this will provide another rare opportunity to detect hidden ocean signals.

TOPICS Earth's Magnetic Field European Space Agency

Sourse: www.livescience.com