MH370 is believed to have been hijacked when it disappeared nearly six years ago – but one of the biggest mysteries is how the hijackers did it so quickly.

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 went missing on March 8, 2014, en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing with 239 people on board. At 17:19 UTC on the night of its disappearance, Lumpur Radar contacted the plane as it was leaving Malaysian-controlled airspace to instruct them to make contact with air traffic controllers in Vietnam. Lumpur Radar said: “Malaysia 370, contact Ho Chi Minh 120.9. Goodnight.”

The last words from MH370 were: “Goodnight, Malaysia 370.”

The words were apparently said calmly with no indication that something bad was about to happen.

Just two minutes later, the plane turned 180 degrees and started flying south – thought to be the start of the hijack.

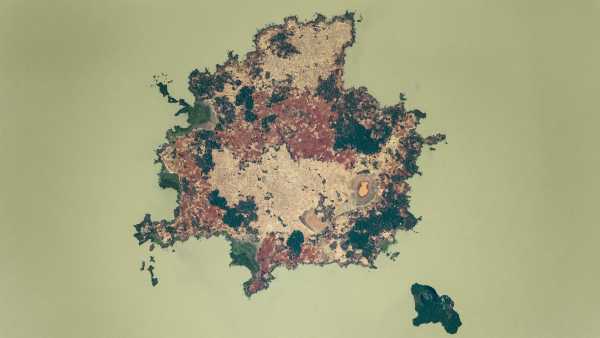

The flight path of the plane after this indicates a hijacking – the plane flew in zigzags along the boundary between different countries’ air traffic control boundaries, thus avoiding detection.

While a hijacking is the rational conclusion, two minutes is an incredibly short space of time for someone to be able to take over the plane via the cockpit.

Aviation expert Jeff Wise explained in his 2015 book ‘The Plane That Wasn’t There’ that the plane could have been hijacked by someone in the flight crew, for example the pilot of copilot, or someone else on deck.

However, he added that one of these possibilities was initially more believable than the other.

He wrote: “Of the two possibilities, the evidence initially available strongly favours the first, since only two minutes had elapsed between the calmly enucnicicated ‘goodnight, Malaysia 370’ and the start of the 180 degree turn.

“This was very little time for hijackers to get through the closed cockpit door, overpower the flight crew, turn off all communications and reprogramme the flight computer.

“And in any event, it seemed hard to imagine how hijackers could do all that without the flight crew sending out some kind of distress signal.

“It seemed much more plausible that either the pilot of the copilot had absconded with the plane.”

However, he later suggested another possibility – that the plane was taken over from somewhere other than the cockpit, somewhere much easier to access that can be used to override the controls in the cockpit without the pilots realising.

DON’T MISS

MH370: Why expert dismissed controversial theory with ‘Bond film’ snub [VIDEO]

MH370: Pilot’s ally was sent to prison hours before disappearance [REVEALED]

MH370: How hijacker could ‘incapacitate entire plane in 35 seconds’ [EXPERT]

The key to this is a piece of equipment called the Satellite Data Unit (SDU), which is an integral part of the plane’s satcom.

It processes the signals that are transmitted and received between the plane and a satellite unit – in MH370’s case, a satellite called 3F1 owned by th British satellite telecommunications company Inmarsat.

The SDU located above the ceiling of the passenger cabin towards the back of the aeroplane.

In the hours after MH370’s disappearance, the SDU was turned off and on again, meaning the hijacker must have accessed it.

It is known that it was turned off and on again because, for a while, satellite 3F1 failed to make contact with MH370, but then contact was reestablished.

At 17:07 UTC the plane sent an Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) report via the SDU to satellite 3F1.

At 17:37 UTC, the next ACARS message was due to be sent did not take place.

At 18:03 UTC, Inmarsat attempted to contact MH370 but received no response, indicating that the satcom system was turned off or otherwise out of service.

Then, at 18:25 UTC, MH370 initiated a log-on with 3F1 – it was coming back online.

This then allowed information to be passed to Inmarsat via seven handshakes over the next few hours, which were later tracked to a flight path over the Indian Ocean, terminating in the sea west of Perth, Australia, where it is believed the plane went down.

As MH370’s SDU was made by Honeywell instead of Rockwell Collins, it can be accessed via the Electronics and Equipment Bay (EE Bay).

The EE Bay is a compartment that, in a Boeing, is accessible during flight through an unlocked hatch on the floor at the front of the first class cabin.

Trending

A hijacker could climb into the EE Bay from the passenger cabin to meddle with the SDU.

In fact, according to Mike Exner, an MH370 investigator from a group of experts called the Independent Group, claimed that this is the only place where it can be accessed – not the cockpit.

In 2014, Mr Exner gained access to a major US airline’s professional-grade flight similar facility and asked two veteran Boeing 777 pilots who accompanied him how the SDU could be turned off and on again.

He reported back: “There is no way to turn off the primary power to the satcom from the cockpit.

“It is not even described in the flight manuals. The only way to do it is to find an obscure circuit breaker in the EE Bay.”

The SDU can also be meddled with by unplugging the Internal Reference System (IRS), which feeds information to the SDU, and plugging in your own equipment.

Therefore, the perpetrator could have hijacked the plane by climbing into the EE Bay and taking over the plane from there.

They could even have made sure that the pilots still thought they were controlling the plane through “phantom controls”.

In this way, this could explain how someone other than the pilot or copilot could have hijacked the plane so quickly – they did not even need to enter the cockpit.

Sourse: www.express.co.uk