The giant Thwaites Glacier is one of the fastest-melting glaciers on the coast of Antarctica, and scientists are trying to find out why.

A robotic submarine is about to descend into a dark, water-filled cavern in Antarctica, to try to find out why one of the continent’s largest glaciers is melting so fast.

In the next few days, scientists will lower the torpedo-shaped robot, dubbed Icefin, into a nearly 2,000-foot-long (600 meters) borehole in the ice of Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica. Previously, scientists used Icefin robots to study the sea life beneath the ice in the Ross Sea off of Antarctica, but this new project has a different purpose.

A key aspect of the robot’s mission will be to study the glacier’s “grounding line,” the point where it separates from the continental bedrock and starts to float on the waters of the Amundsen Sea.

The Thwaites Glacier covers more than 74,000 square miles (192,000 square kilometers) — an area larger than Florida — and is more than 900 miles (1,500 km) from the nearest U.S. and British Antarctic research bases. It’s one of Antarctica’s fastest-melting glaciers, having lost an estimated 595 billion tons (540 billion metric tons) of ice since the 1980s. Observations indicate that the glacier is now melting even faster than before, and scientists want to find out why.

They are also concerned that the melting of the large coastal glacier could expose some inland glaciers nearby to further melting, causing sea levels to rise by up to 6 feet (2 m).

Thwaites Glacier could be “a keystone to triggering ice loss from neighboring portions of West Antarctica,” said Paul Cutler, program director of glaciology, ice core science and geomorphology at the National Science Foundation. “The question is, how much sea level rise, and how fast?”

Cutler is the U.S. program director for the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a multi-year study involving more than 60 scientists from several countries.

The submarine robot project, t,named MELT, is one of eight major ITGC projects on the Thwaites Glacier supported by the U.S. Antarctic Program and the British Antarctic Survey. .

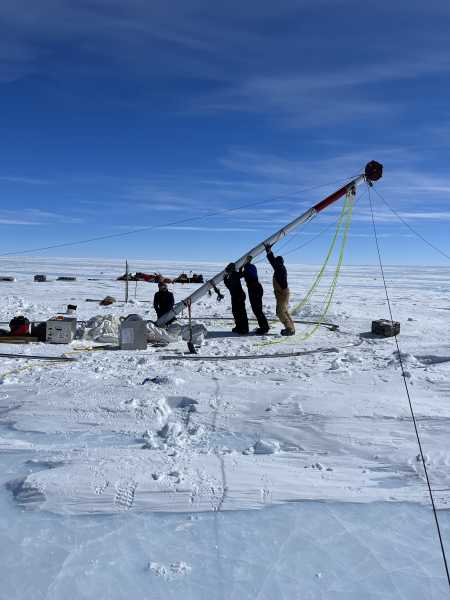

Melting through the iceThe researchers have melted and drilled a borehole through almost 2,000 feet (600 meters) of the Thwaites Glacier to deploy a submarine robot into the water-filled cavity below it.

The MELT project scientists flew out to the Thwaites Glacier a few weeks ago and are now camped out on its eastern ice tongue. They have melted and drilled out a 20-inch-wide (50 centimeters) access hole through the ice near its grounding line, Cutler told Live Science in an email.

In the coming days, they will lower the Icefin robot through the ice to explore a vast cavity, two-thirds of the area of Manhattan, which researchers using ice-penetrating radar discovered beneath the glacier last year.

Icefin is equipped with high-definition video cameras, sonar and instruments for monitoring water flow, salinity, oxygen and temperature.

The borehole through the ice of the Thwaites Glacier is near the “grounding line,” where it leaves the Antarctic bedrock and starts floating on the Amundsen Sea.

After the scientists deploy Icefin, they plan to recover it three or four days later, before the hole freezes over.

Icefin will send back live pictures to the scientists so they can guide the robot to the glacier’s grounding line. Once there, it will take sediment samples and measure the amount of fresh water flowing out to sea from the glacier as it melts.

ITGC scientists have only a few weeks left before the weather on the remote glacier starts to get worse with the approach of the southern polar winter. The final part of the ITGC operation this season will take place in late January, when a U.S. research ship leaves Chile for the Amundsen Sea to collect data from the ocean floor near Thwaites Glacier, Cutler said.

The ITGC is the largest joint U.S.-U.K. scientific operation undertaken in Antarctica in the past 70 years, and it has required an extraordinary amount of planning to deal with the freezing weather and remote location of Thwaites Glacier.

It took the U.S. Antarctic Program and the British Antarctic Survey two years to prepare the logistics of the operation, and the scientific projects were planned long before that. “Aa program of this magnitude is years in the making, Cutler said.”

The implications of the project, however, are not Earthbound. Engineers hope that the technology they’re using for Icefin one day will be used to search for life in other ice-covered oceans in the solar system, such as the liquid oceans thought to exist beneath the icy crusts of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Sourse: www.livescience.com