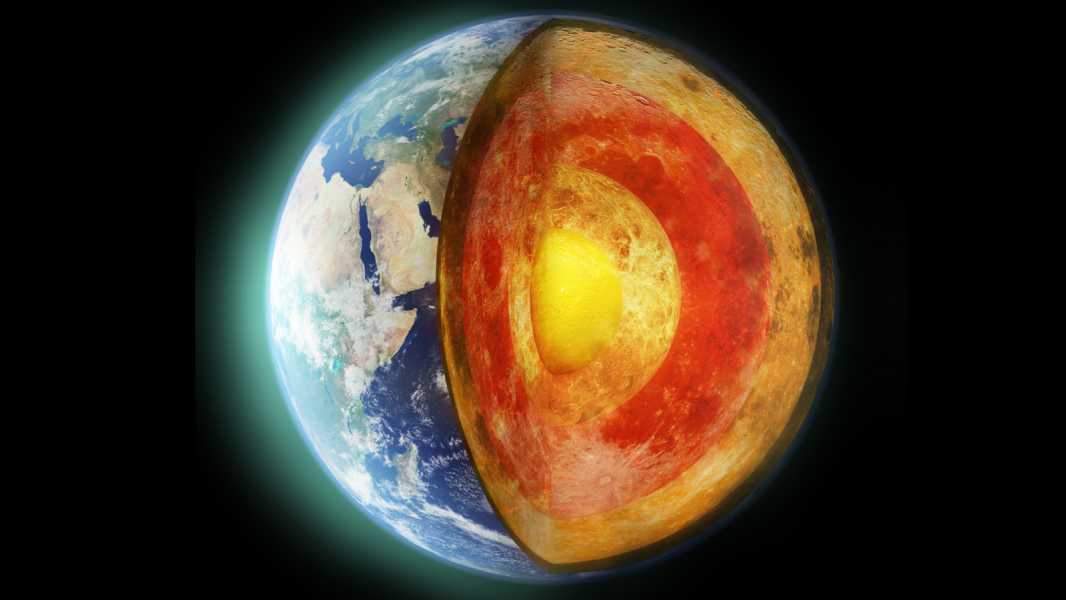

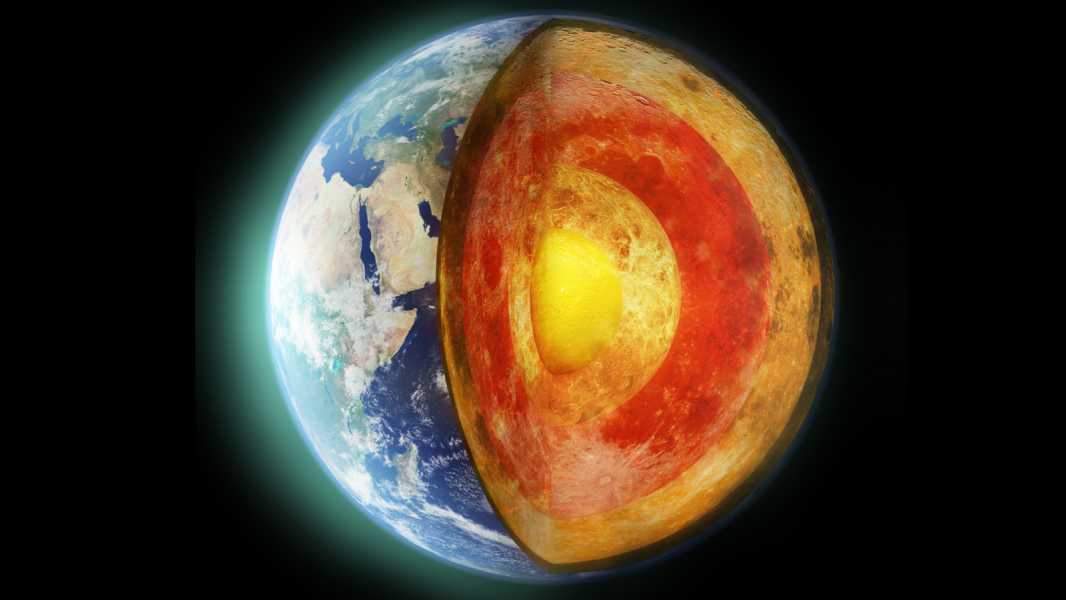

Two huge lumps deep in the Earth's interior are apparently the remains of oceanic crust that was submerged into the mantle. (Image credit: Yuri_Arcurs/Getty Images)

We've finally figured out where the two giant clumps in Earth's middle layer are coming from – and they form an incompatible pair.

New research suggests that these unusual zones in the Earth's mantle, known as “large low-velocity provinces” (LLVPs), are actually fragments of the Earth's crust that have sunk into the mantle over the past billion years.

Scientists have long recognized the existence of LLVPs — one beneath the Pacific Ocean and one beneath Africa. In these areas, seismic waves from earthquakes travel 1 to 3 percent slower than in the rest of the mantle. Researchers speculate that they may affect the planet’s magnetic field through their influence on heat flow from the Earth’s core.

There is much debate about what LLVP is. Some studies suggest it is material from the ancient Earth—either a layer of primordial, unmixed rock from when the planet formed, or the remnants of a huge cosmic body that slammed into Earth 4.5 billion years ago, creating the Moon.

Other researchers suggest that the blobs represent vast tracts of oceanic crust that have been pushed into the mantle by one tectonic plate sliding beneath another, a process called subduction.

The crust hypothesis has not been explored as much as the ancient material idea, said James Panton, a geodynamicist at Cardiff University in the U.K. In a new study published Feb. 6 in the journal Scientific Reports, he and his colleagues used computer modeling to determine where subducted crust has sunk into the mantle over the past billion years and whether that subducted crust could have formed structures similar to LLVPs.

“We found that recycling of oceanic crust can actually create these LLVP-like regions beneath the Pacific and Africa without the need for an initially dense layer at the base of the mantle,” Panton told Live Science. “They form on their own, simply through the process of subduction of oceanic crust.”

That doesn't mean there's no dense material from the young Earth in the lower mantle, Panton noted; there may be a thin layer of ancient material that also contributes to LLVP formation. But if subduction alone can explain LLVPs, that could give an indication of their age.

“This potentially implies that shortly after subduction began on Earth, that’s probably when LLVPs emerged,” Panton said. (The emergence of subduction itself is a complex issue. Some researchers believe it began more than 4 billion years ago, while others suggest it began about a billion years ago.)

The subduction process has produced two different types of blobs, the study authors say. The LLVP beneath Africa is currently not receiving as much crustal material as the LLVP beneath the Pacific, which is fed by subduction zones of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a horseshoe-shaped subduction line that encircles the Pacific Ocean.

So the African LLVP is older and better mixed with the rest of the crust, the team said. It also has less of the volcanic rock known as basalt, meaning it is less dense than the Pacific LLVP. That could explain why the African LLVP extends 342 miles (550 kilometers) higher in the mantle than the Pacific LLVP.

One question for the future, Panton said, is how hot regions of the mantle, called mantle plumes, might influence the subduction process in the Pacific Ocean and affect the LLVP. These plumes extend from the very bottom of the mantle to volcanic hotspots on the surface, such as the Hawaiian Islands.

Quiz “What's Inside the Earth”: Test Your Knowledge of the Hidden Layers of Our Planet

Sourse: www.livescience.com