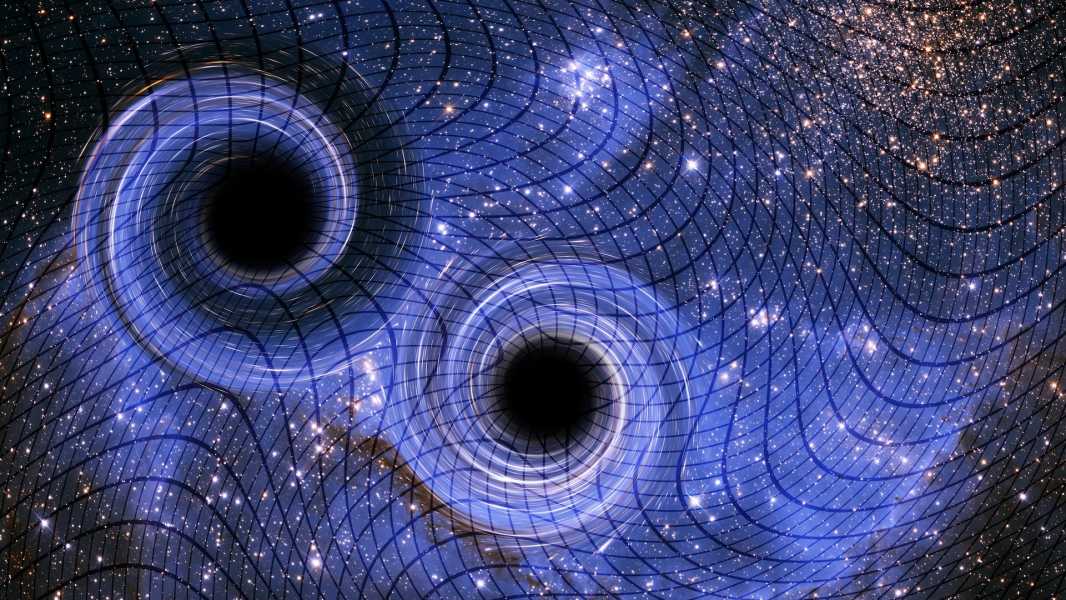

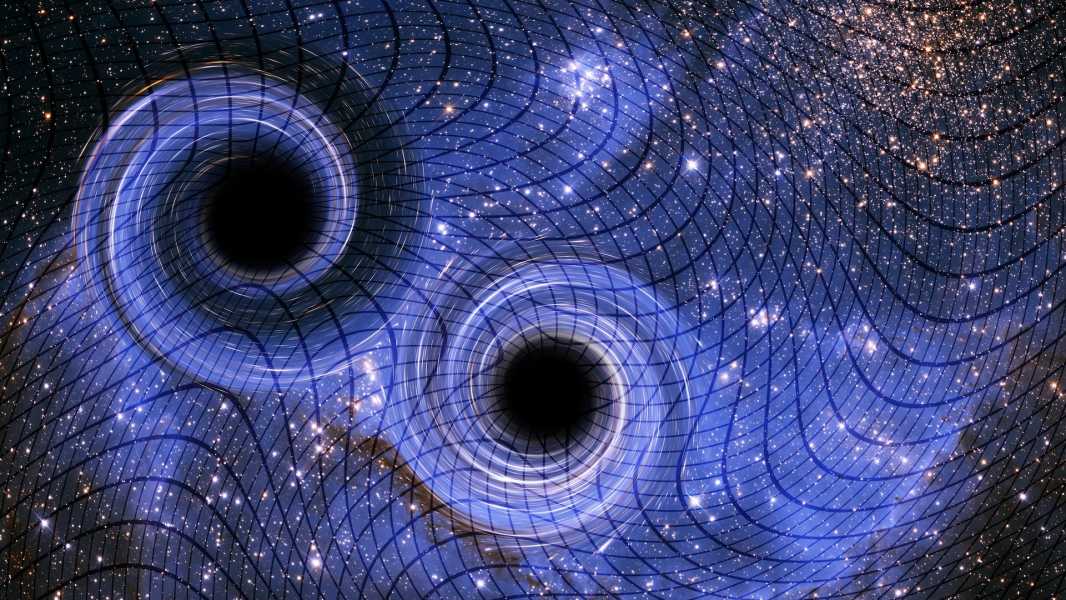

As black holes spiral toward a collision, they emit gravitational waves that spread out across the universe in a series of oscillations. New research suggests that traces of the universe's earliest black hole mergers may be imprinted in the fabric of space-time. (Image credit: VICTOR de SCHWANBERG/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY via Getty Images)

A team of theoretical physicists has proposed a new way to test one of the most exciting predictions of Einstein's general theory of relativity: gravitational memory.

The effect is due to a constant change in the structure of the universe caused by the passage of space-time oscillations known as gravitational waves. Although these waves have already been detected by observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Virgo interferometer, the residual trace of the waves remains elusive.

Researchers suggest that the cosmic microwave background — the faint glow left over from the Big Bang — may contain traces of powerful gravitational waves from distant black hole mergers. Studying these signals could not only confirm Einstein’s prediction, but also shed light on some of the most energetic events in the history of the universe.

“Observing this phenomenon could give us more knowledge about different areas of physics,” Miquel Miravet-Tenes, a PhD student at the University of Valencia and co-author of the study, told Live Science via email. “Since it is a direct prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, observing it would be a confirmation of the theory, just like the gravitational wave observations of LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA [the Kamioka Gravitational Wave Detector] did! It could also be used as an additional tool to study some astrophysical scenarios, as it could contain information about the types of events that generate memories, such as supernovae or black hole collisions.”

How Gravitational Waves Leave a Trace in Space

According to general relativity, massive objects that warp spacetime can create ripples that travel through the universe at the speed of light. These gravitational waves occur when massive bodies accelerate, such as when two black holes spiral toward each other and merge.

Unlike ordinary waves, which pass through matter and leave it unchanged, gravitational waves can permanently alter the structure of spacetime itself. This means that any objects they pass through, including elementary particles of light known as photons, can experience a lasting change in speed or direction. As a result, light traveling through space can retain the memory of past gravitational wave events imprinted in its properties.

The researchers explored the possibility of detecting this effect in the cosmic microwave background, a relic field of radiation that has been traveling through space since the universe was a fraction of a percent of its current age. Subtle changes in the temperature of this radiation could contain clues about gravitational waves from ancient black hole mergers.

“We can learn a lot of things,” Kai Hendrix, a graduate student at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen and another co-author of the study, told Live Science in an email. “For example, measuring the gravitational memory in a gravitational wave signal gives us more information about the properties of the two black holes that produced the signal; how heavy these black holes were; or how far away they are from us.”

But the implications go beyond individual black hole mergers. If a trace of gravitational memory can be detected in the cosmic microwave background, it could reveal whether supermassive black holes merged more frequently in the early universe than they do now. This could provide new insights into how galaxies and black holes have evolved over cosmic time.

Sourse: www.livescience.com