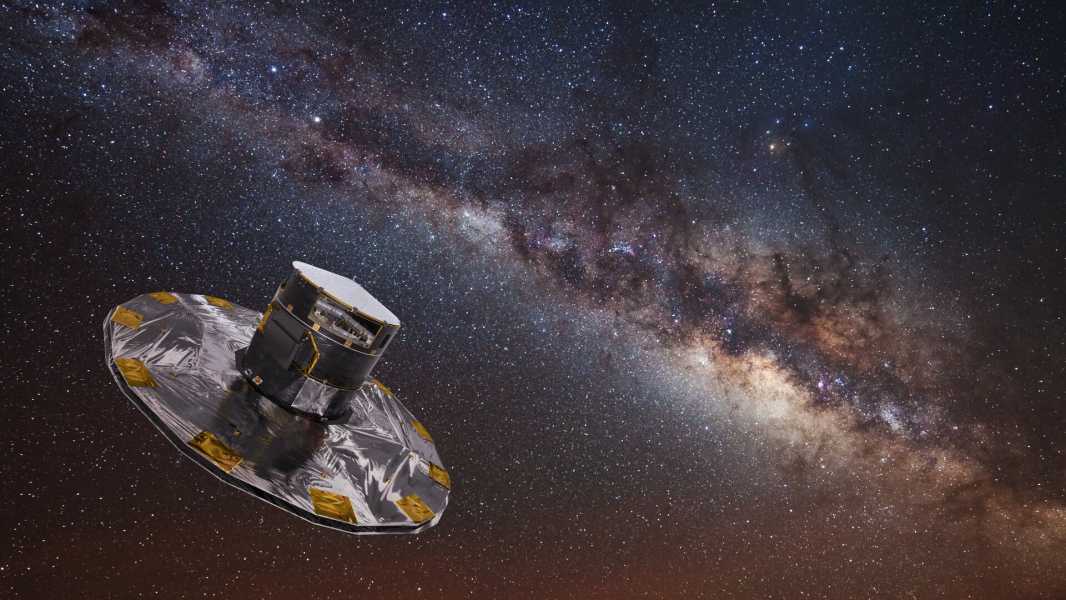

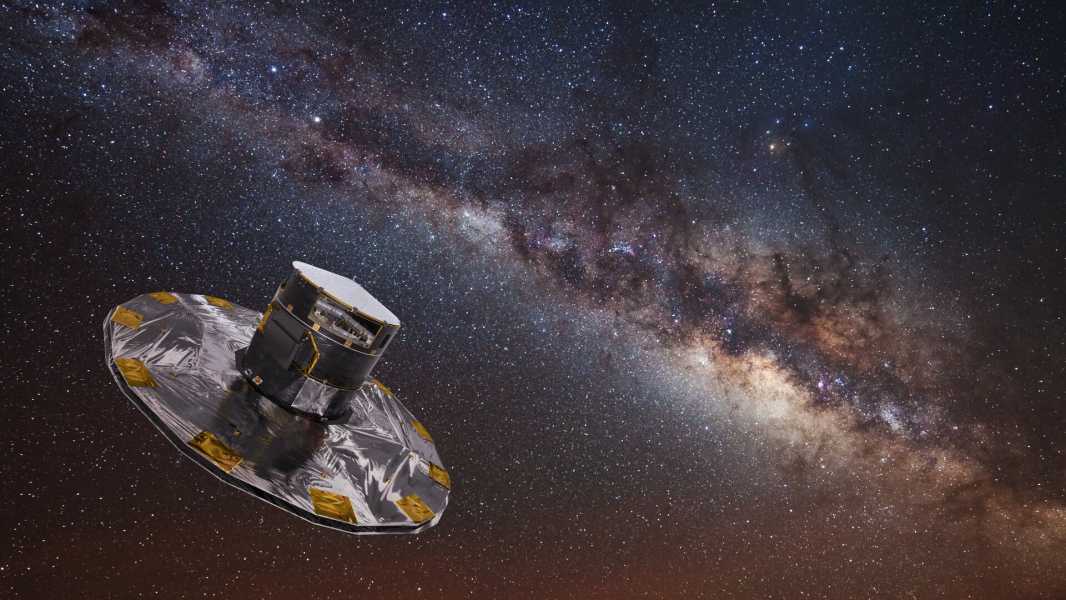

An artist's impression of the Gaia telescope mapping the stars of our Milky Way galaxy. (Image credit: ESA/ATG medialab; background: ESO/S. Brunier)

On March 27, scientists bid farewell to the Gaia telescope, ending its revolutionary 11-year mission to map the Milky Way and surrounding cosmic objects.

While Gaia is not as well-known as some of its peers, such as the Hubble or James Webb Space Telescopes, it has significantly changed our understanding of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Since 2014, the European Space Agency (ESA) telescope has scoured the cosmos, creating a vast catalog of nearly 2 billion stars, more than 4 million potential galaxies, and about 150,000 asteroids, with moons possibly orbiting hundreds of them.

These observations have been the basis for more than 13,000 scientific publications, and this number is likely to increase in the future.

“The vast data that Gaia publishes constitutes a unique resource for astrophysical research and has an impact on virtually every area of astronomy,” said Johannes Sahlmann, a physicist at the European Space Astronomy Centre in Spain and a Gaia mission scientist, in a statement.

After 11 years of operation, almost twice its planned lifetime, Gaia ran out of fuel, forcing ESA operators to turn off power and decommission the spacecraft.

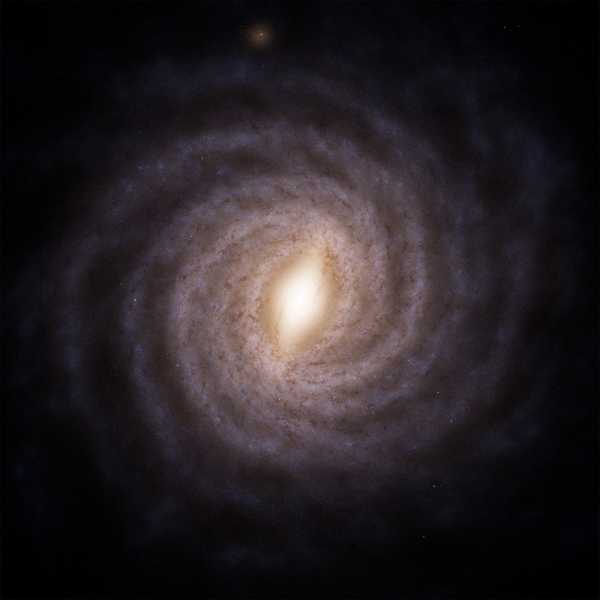

The best map of the Milky Way galaxy

Since its launch in December 2013, Gaia has been mapping the cosmos from a vantage point about a million miles (1.6 million kilometers) from Earth, in a region known as Lagrange point 2 (L2), where the gravitational forces of the Earth and the Sun, as well as the orbital motion of the satellite, are in equilibrium.

Gaia's main mission was to map the positions and movements of more than a billion stars within the Milky Way, creating the largest and most accurate three-dimensional map of our galaxy. To do this, it was equipped with two telescopes pointing in different directions to measure the distances between stars, while three onboard instruments collected data on the positions, speeds, colors, and chemical compositions of celestial bodies.

The precise map of our galaxy it created allowed scientists to better understand the galaxy's spiral structure, estimate the shape and mass of the dark matter halo surrounding the Milky Way, and solve a long-standing mystery about our galaxy's warped and wobbling disk, which is likely the result of an ongoing collision with the smaller Sagittarius galaxy.

The catalogue also provided astronomers with new insights into the ancient nature of parts of our galaxy, suggesting that stars began forming in the Milky Way's disk less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang – well ahead of the previously accepted time frame of 3 billion years.

Sourse: www.livescience.com