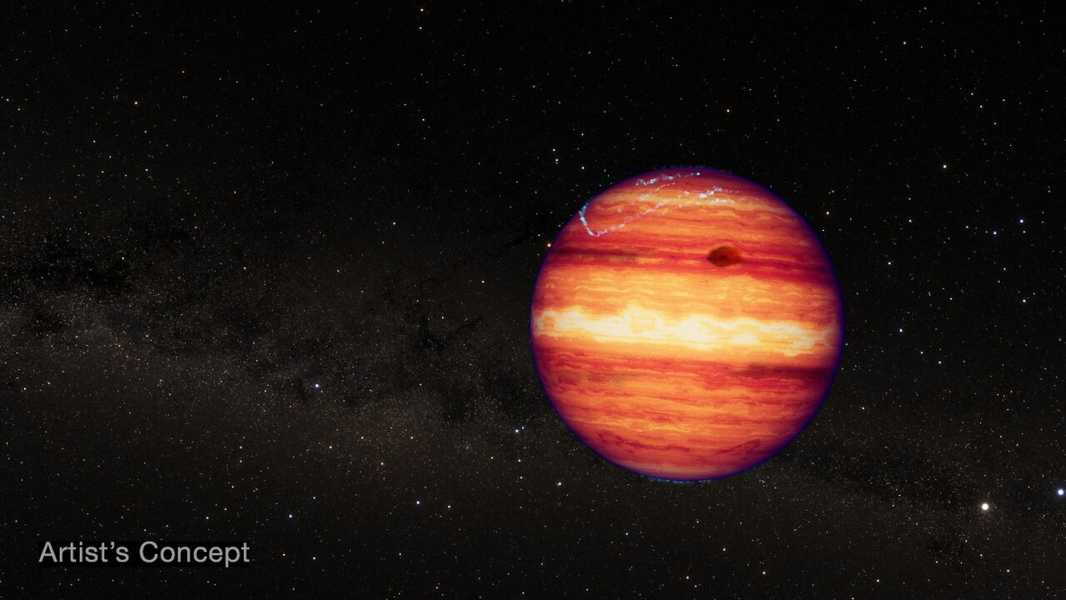

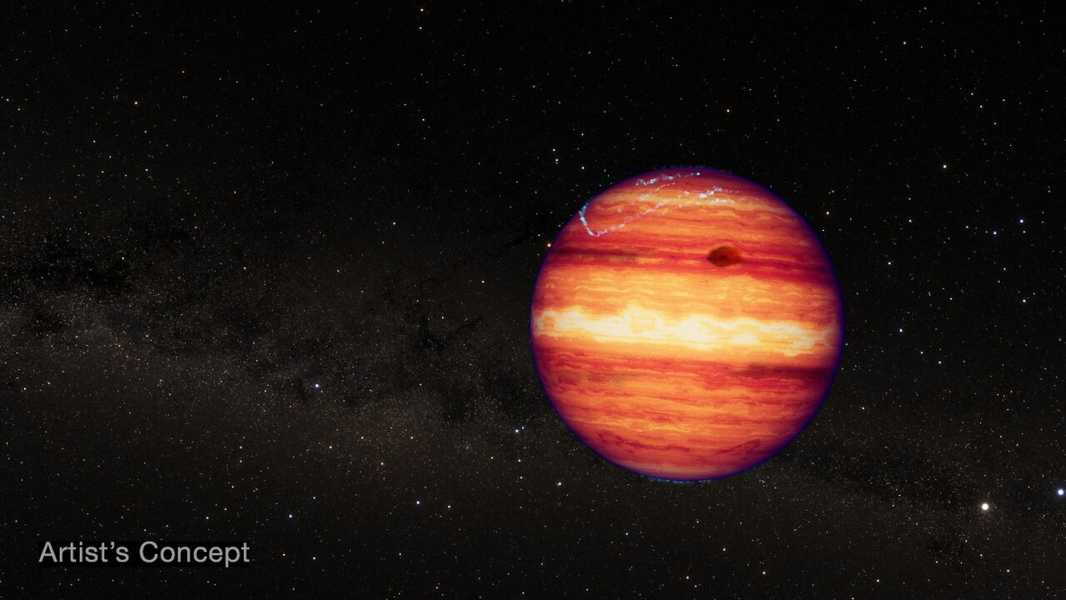

An artist's illustration of SIMP 0136+0933. This astronomical object is the brightest starless body visible in the Northern Hemisphere sky. (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI))

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists have produced the first-ever weather forecast for an exoplanet that features cloud regions and carbonaceous materials, as well as high auroras.

The results of the study, published March 3 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, also indicate that the celestial object has a complex, multi-layered atmosphere.

The Earth's atmosphere is a gaseous envelope, mostly made up of nitrogen and oxygen. However, atmospheric conditions on other planets in the solar system vary greatly. For example, the atmosphere of Venus is much denser than that of Earth and is toxic, consisting of sulfuric acid. This diversity of atmospheres is also observed among exoplanets: some have water-vapor-saturated atmospheres, while others contain superheated clouds of sand.

The researchers are now pointing JWST at a mysterious object called SIMP 0136+0933 to better understand its atmosphere. The object's identity is still unclear, said lead study author Allison McCarthy, a graduate student in astronomy at Boston University.

“[I]t’s not a planet in the traditional sense — since it’s not orbiting a star,” she told Live Science in an email. However, “it’s also less massive than a typical brown dwarf [a so-called “failed star”],” she added.

SIMP 0136+0933 has a day lasting 2.4 hours and is located in the Carina Nebula, 20 light-years away. Because it is the brightest free-floating planetary-mass object in the Northern Hemisphere and is far from stars that would otherwise obscure observations, it has been directly imaged by telescopes such as NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. These observations have shown that SIMP 0136+0933 has an unusually variable atmosphere, with fluctuations in the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum (which humans perceive as heat). However, the physical causes of this variability have remained unknown until now.

To understand these processes, McCarthy and his colleagues used JWST’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph to measure the intensity of short-wavelength radiation emitted by SIMP 0136+0933. They collected about 6,000 such data sets over nearly three hours on July 23, 2023, covering the entire object. They then repeated the process for longer wavelengths over the next three hours using the space telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument.

As a result, the researchers created light curves to show how the “brightness” (or intensity) of the infrared radiation changed over time. These curves showed that different wavelengths behaved differently. At any given moment, some became brighter, others dimmed, and others remained stable. However, the researchers found that the light curves formed three clusters, each with a characteristic — if somewhat variable — shape.

Sourse: www.livescience.com