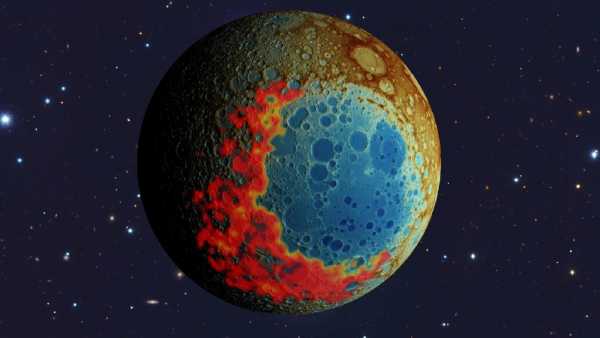

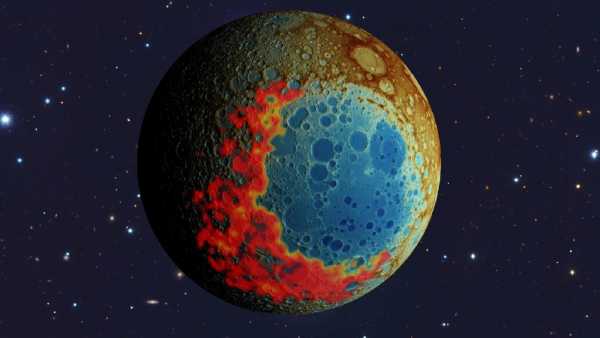

A recent investigation has demonstrated that the space rock that gave rise to the South Pole-Aitkin basin (blue) emitted radioactive lunar matter, identified as KREEP (red), that encompasses the crater’s southwestern perimeter.(Image credit: Jeff Andrews-Hanna/University of Arizona/NASA/NAOJ)

According to a fresh study, the moon’s biggest and most ancient depression didn’t originate as previously assumed. The conclusions imply that a certain locale on the lunar terrain may possess greater scientific importance than initially believed, which could profoundly impact NASA’s forthcoming Artemis missions, slated to set down astronauts in this recently recognized zone of attention as early as 2027.

The moon came into being around 4.46 billion years ago, stemming from a monumental clash between an archaic Mars-sized protoplanet, termed Theia, and Earth. This collision produced an immense scattering of rubble that ultimately coalesced into a substantial spherical celestial body orbiting our globe. Over the ensuing roughly 200 million years, the lunar face was blanketed in a fiery sea of magma, a consequence of gravitational compression exerted by Earth. However, as the moon drifted further from our planet, the molten substance gradually solidified and crystallized, giving rise to an external rocky shell that has largely persisted in its primary state ever since, with the exception of consistent impacts from cosmic debris.

You may like

-

Scientists scan famous ‘Earthrise’ crater on mission to find alien life in our solar system

-

Earth may have at least 6 ‘minimoons’ at any given time. Where do they come from?

-

Cataclysmic crash with neighboring planet may be the reason there’s life on Earth today, new studies hint

It is inferred that KREEP originated during the closing cooling phase of the moon, wherein radioactive components amassed in the space separating the moon’s freshly formed mantle and shell. Further scrutiny of these components could aid in illuminating various uncertainties surrounding this epoch of lunar development, notably the reason behind the lunar far side’s crust being denser than its readily visible near side.

Heretofore, investigators had theorized that the SPA basin came into existence from an asteroid hitting the moon from the south, which would have dispersed a coat of KREEP around the crater’s northern perimeter. Nevertheless, a new analysis, shared Oct. 8 in the journal Nature, revealed that the collision actually occurred from the north. That indicates the resulting KREEP is layered around the southern border of the depression — exactly where the manned Artemis III endeavor is scheduled to touch down.

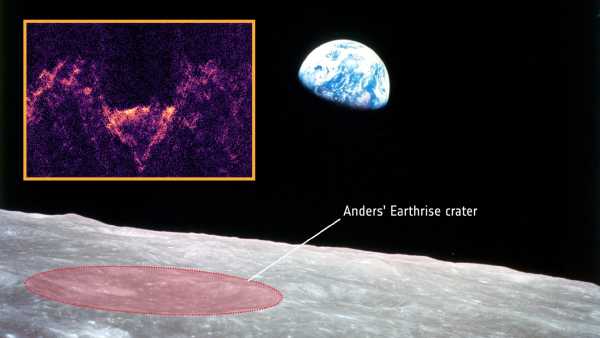

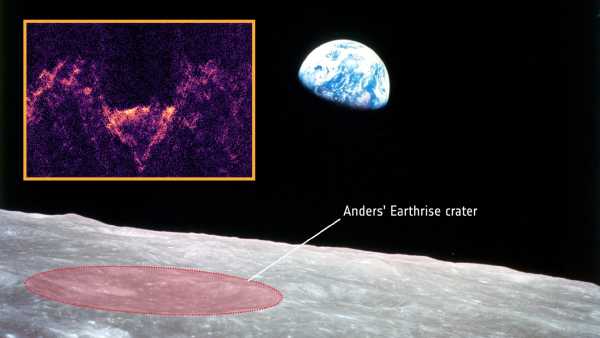

This image, captured by the Apollo 8 astronauts back in December 1968, exhibits the lunar mountains surrounding the northern edge of the South Pole-Aitken basin.

“This means that the Artemis missions will be touching down on the basin’s distal rim — the prime spot to scrutinize the moon’s largest and most ancient impact site,” indicated study leading author Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a planetary expert at the University of Arizona, in a statement. This is “where the bulk of the ejecta, substance originating from the depths of the moon’s core, ought to have collected,” he further mentioned.

The team started to question the SPA basin’s actual beginnings as they matched its form against other impact craters dispersed across the solar system, like Mars’ Hellas basin and Pluto’s Sputnik basin. All three depressions share a comparable configuration, exhibiting a rounded extremity and a more pointed one, leading to their likeness to an avocado or teardrop. The pointy end of these formations is likely indicative of the impact’s path, allowing the team to infer the direction from which the SPA basin asteroid struck.

These hunches solidified when the team assessed information gathered from the Lunar Prospector, a NASA probe that orbited the moon spanning 1998 to 1999 and gauged the radioactivity of surface elements. This exposure unveiled a heightened density of thorium — a radioactive constituent and essential component of KREEP — around the crater’s southwestern border.

Collecting KREEP-y samples

The unmanned Orion capsule belonging to the Artemis I mission orbited the moon for roughly two weeks in late 2022.

The Artemis III mission, designed to position humans on the moon for the inaugural time since 1972, is presently projected for mid-2027, succeeding the execution of the Artemis II undertaking, which is slated for liftoff at some juncture before the close of April 2026. The initial mission will deploy a manned spacecraft to revolve around the moon, echoing the unmanned Artemis I spacecraft, which achieved a successful lunar orbit in late 2022.

The Artemis III astronauts will alight near the moon’s southern pole in one of nine prospective locations, with the majority situated within the KREEP diffusion area encircling SPA, as stated by NASA. Should they come down in the suitable zone, this could offer the group the chance to gather valuable KREEP specimens.

Nevertheless, ambiguity clouds the actual launch date for Artemis III.

RELATED STORIES

—Will Earth ever lose its moon?

—How long does it take to travel to the moon?

—What temperature is the moon?

Both Artemis II and Artemis III have undergone several postponements. Propose cuts to NASA’s 2026 funding, which are historically substantial, have also steered some specialists to foresee additional delays. This could potentially grant China an upper hand in the competition to reinstate human presence on the moon.

China has also effectively procured initial samples from the moon’s far side, transported back to Earth during June 2024 by the Chang’e 6 spacecraft, operating within the SPA basin. Yet, in spite of apportioning the precious lunar fragments with various other nations, NASA is yet to be permitted to analyze these samples.

Moon quiz: What do you know about our nearest celestial neighbor?

Harry BakerSocial Links NavigationSenior Staff Writer

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won “best space submission” at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the “top scoop” category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science’s weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Scientists scan famous ‘Earthrise’ crater on mission to find alien life in our solar system

Earth may have at least 6 ‘minimoons’ at any given time. Where do they come from?

Cataclysmic crash with neighboring planet may be the reason there’s life on Earth today, new studies hint

‘City killer’ asteroid could be nuked before close encounter with the moon

Dozens of mysterious blobs discovered inside Mars may be the remnants of ‘failed planets’

New ‘quasi-moon’ discovered in Earth orbit may have been hiding there for decades

Latest in The Moon

Harvest supermoon photos: See the moon at its biggest and brightest in pictures from around the world

The full Harvest Moon supermoon rises tonight

Sourse: www.livescience.com