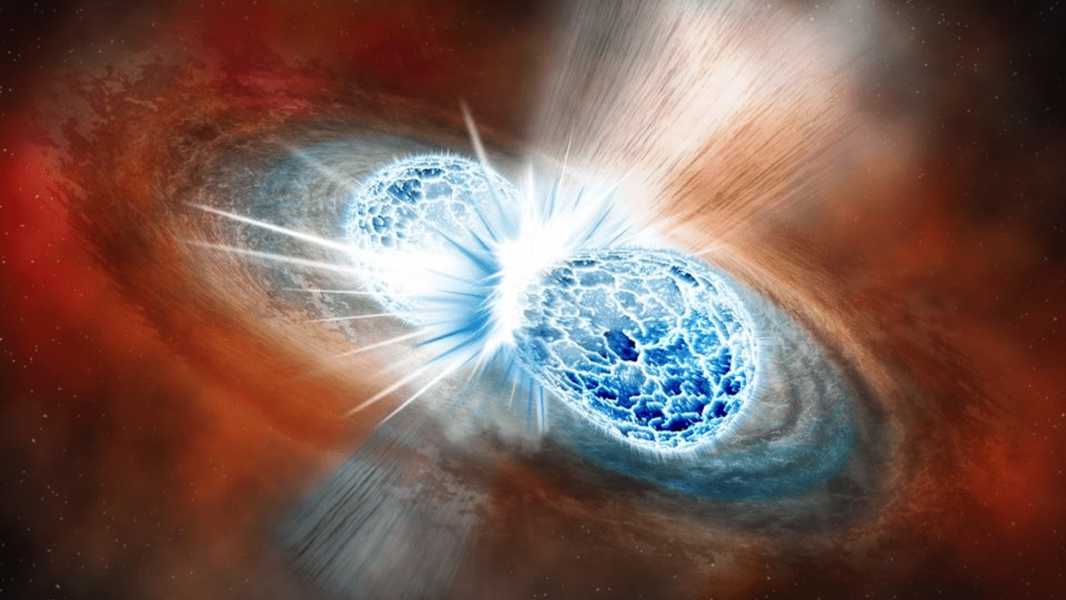

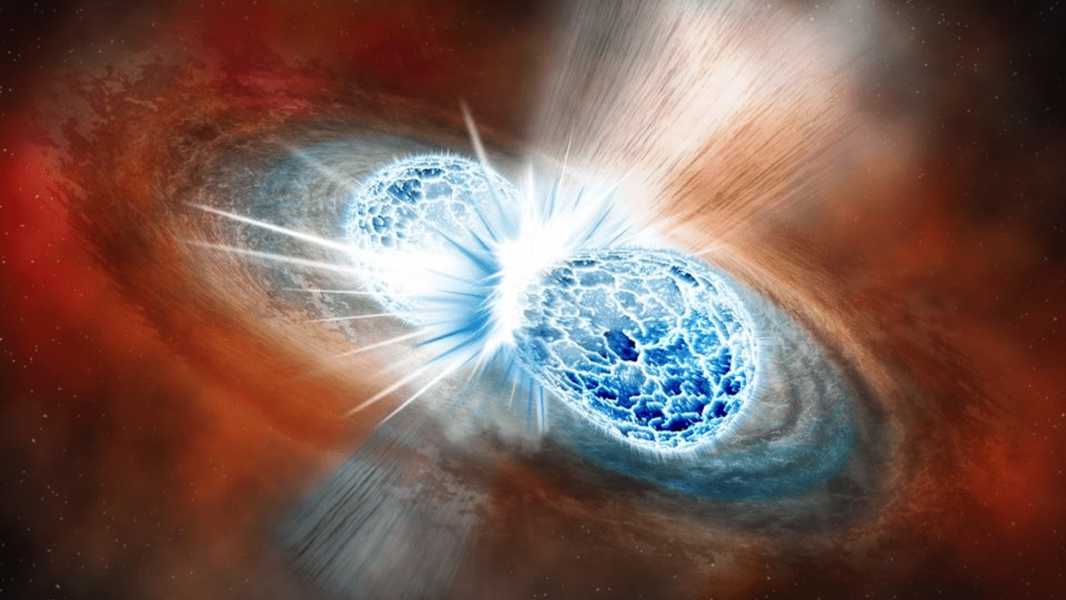

An artist's impression of two neutron stars colliding in a kilonova. (Image courtesy of NASA)

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Debris from some of the most powerful explosions in the universe is closer than you might think. In fact, you may have encountered it during your last swim in the ocean.

By analyzing deep sea samples, researchers have identified a unique isotope of radioactive plutonium that appears to be the remains of a rare type of cosmic explosion known as a kilonova that occurred near Earth about 10 million years ago. However, more data will be needed to definitively confirm the event, and scientists are confident they know where to find it: on the surface of the Moon.

“We’re in a supernova graveyard,” said Brian Fields, an astronomer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in a March 17 talk at the American Physical Society’s 2025 Global Physics Summit. “[Supernovae] create tiny particles that can literally rain down on Earth. They accumulate on the ocean floor and they also end up on the moon.”

Fields has been developing his theories about space debris since the 1990s. But it wasn’t until 2004 that scientists began separating supernova remnants from ocean samples. They found traces of a radioactive version of iron that doesn’t occur naturally on Earth and can only be explained by a recent supernova’s close approach to our planet.

In the years since, about a dozen samples from the ocean and the moon have helped paint a more complete picture of this explosive history. Fields and his colleagues’ refined theories have pointed to two separate supernova events, occurring 3 million and 8 million years ago. “This is direct observational evidence that supernovae are sources of radioactivity,” Fields said.

Space cocktail

Things got more complicated in 2021, when researchers found an even rarer substance among the same samples: a radioactive isotope of plutonium. That discovery required a more unusual origin story than the harsh ends of stars that lead to supernovae.

The plutonium variant discovered is thought to have originated from kilonovae, explosions that occur when two neutron stars orbit each other and collide in a cataclysmic finale. Kilonovae also act as “factories” for some of the rarest elements on our planet, such as gold and platinum, and astronomers have long tried to unravel the mechanisms behind this class of explosions.

Now, Fields and his team suggest that a separate kilonova event preceded two previously identified supernovae at least 10 million years ago. These different explosions created a kind of radioactive cocktail, introducing hybrid iron-plutonium signatures into the samples.

“We had a kilonova that was producing plutonium — which is what it does — and throwing it all over the place,” Fields explained. “Then when the supernova stirred up the material, it got all mixed up and some of it fell to Earth.”

However, Fields and his team still want to conduct additional tests to confirm their hypothesis. With initiatives like the Artemis missions set to return humans to the moon, researchers are optimistic about the possibility of analyzing lunar samples, which they hope will be in short supply.

“Our lunar soil is so valuable right now because it’s all we have,” Fields told Live Science. “We’re hoping that in the future, regular missions to the moon will make it less of a hassle to collect samples — getting a kilogram won’t be a big deal for people.”

With more available soil, Fields and his colleagues hope to confirm that the kilonova actually happened, as well as figure out when and where it happened. With simpler geology, the Moon should provide a clearer picture of how the debris ended up on its surface.

“On Earth, everything settles to the bottom

Sourse: www.livescience.com