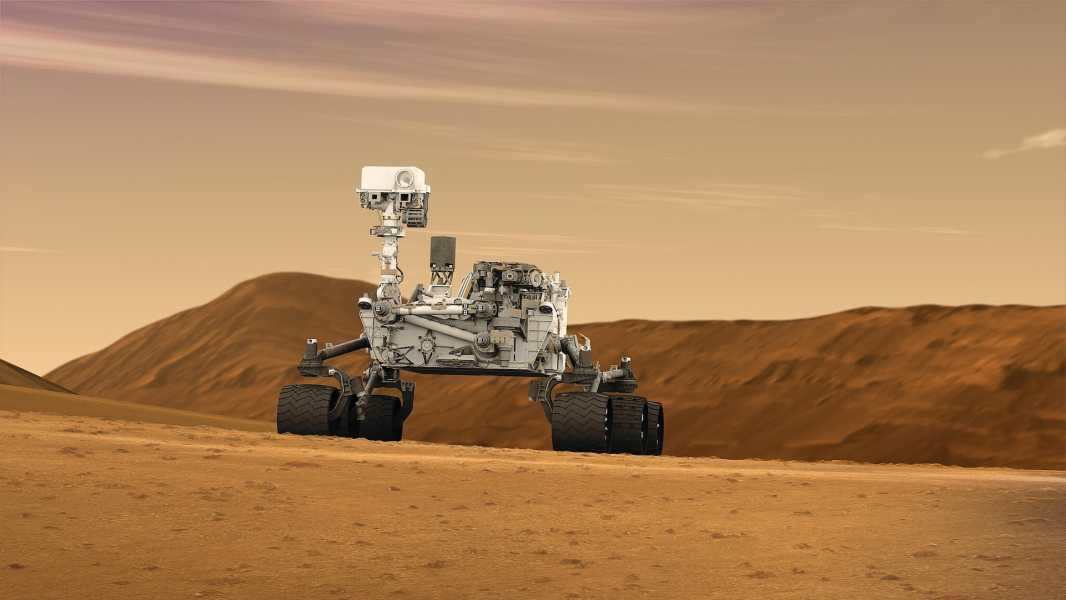

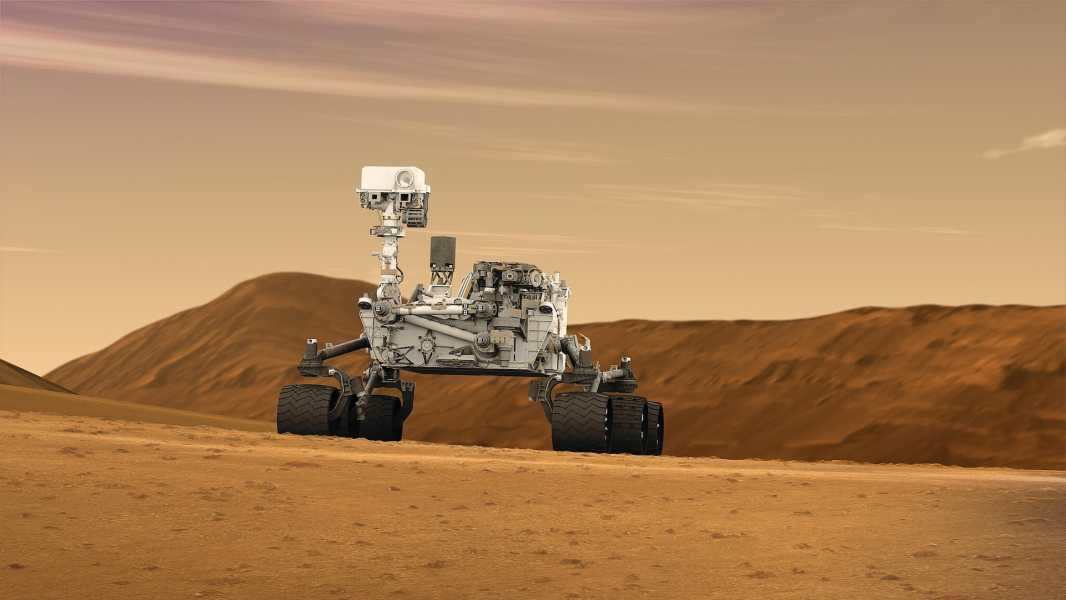

(Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The longest molecules ever found on Mars have been identified by NASA's Curiosity rover, and they may indicate the planet is full of evidence of ancient life.

In a study published Monday (March 24) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, molecular chains of up to 12 linked carbon atoms were found in a 3.7-billion-year-old rock sample collected from a dry Martian lake bed called Yellowknife Bay.

These long carbon chains are thought to have originated from molecules known as fatty acids, which on Earth are formed by biological activity. Although fatty acids can form without the involvement of biology, as may be the case on Mars, their presence on the Red Planet suggests that traces of life may be hidden in its soil.

“The fact that fragile linear molecules are still on the surface of Mars 3.7 billion years after they formed allows us to make a new conclusion: if life ever arose on Mars billions of years ago, then at the moment when life arose on Earth, chemical evidence of that ancient life might still be there for us to detect,” study co-author Caroline Freyssinet, an analytical chemist at the French National Center for Scientific Research's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Spatial Observations, told Live Science.

The molecules – hydrocarbon chains of 10, 11 and 12 carbon atoms called decane, undecane and dodecane – were found using the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument on the Curiosity rover.

No stone was left unturned

The Curiosity rover arrived on Mars in 2012 at Gale Crater, a huge 96-mile-wide (154-km) impact crater formed when an ancient meteorite collided with the planet. Over the course of several years, the rover drove about 20 miles (32 km) across the crater, exploring places like Yellowknife Bay and Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons), which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 km) high at the center of the crater.

The sample analyzed in the new study, called “Cumberland,” was recovered by Curiosity in 2013 from Yellowknife Bay, and previous analyses have shown it to be rich in clay minerals, sulfur and nitrates.

However, despite many careful tests, the hydrocarbon chains in the sample remained undetected for more than a decade. The hydrocarbons were actually discovered by accident during an attempt to find the building blocks of proteins – known as amino acids – in the sample.

The research team behind the new study decided to try a new method of detecting these molecules, preheating the sample to 1,100°C (2,012°F) to release oxygen before analysis. Their results did not reveal any amino acids, but to their surprise, they did find hidden fatty molecules.

“When I first saw the peaks in the spectrum, the excitement was enormous,” Freyssinet said. “It was both surprising and expected. Surprising because these results were obtained on a Cumberland sample that we had tested many times before. Not surprising because we applied a new strategy to the analysis of this sample.”

“New method, new results,” she added.

The researchers suggest that the molecules may have separated from the long tails of fatty acids called undecanoic, dodecanoic, and tridecanoic acids, respectively. Fatty acids are long chains of carbon and hydrogen with a carboxyl (-COOH) acid group at the end.

Sourse: www.livescience.com