“`html

The color of hair might turn gray, in part, since the body is dynamically lessening its vulnerability to cancer, a study on animals reveals.(Image credit: Penpak Ngamsathain/Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Duplicate link

- X

Share this article 4Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a source you prefer on GoogleNewsletterSign up for our newsletter

Hair turning gray could suggest that the organism is successfully defending against cancer, according to a recent piece of research.

Triggers that can instigate cancer, like ultraviolet (UV) rays or some chemicals, set off an inherent protective course that results in early graying while also decreasing the chances of getting cancer, the study showed.

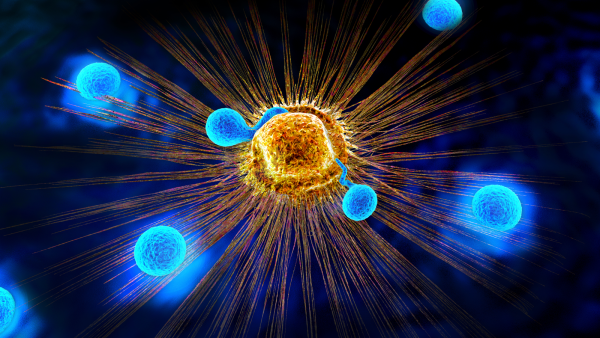

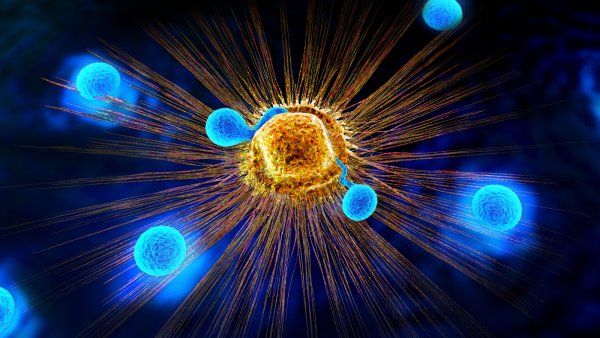

The research team responsible for the study followed what became of stem cells that are in charge of creating the pigment that gives hair its hue. In tests using mice, they deduced that these cells reacted to DNA damage either through halting growth and division — causing hair to become gray — or through duplicating uncontrollably to eventually give rise to a tumor.

You may like

-

We might ultimately grasp stress-induced hair thinning

-

High-fiber nutrition may ‘restore’ immunity cells that combat cancer, study shows

-

Could older eggs be ‘restored’? A novel method might clear a path to treatments that prolong fertility

The discoveries, as indicated in October within the journal Nature Cell Biology, emphasize how crucial these sorts of safeguard approaches are which arise as people age as a means of protection opposing DNA destruction and illness, the study’s writers assert.

Graying hair as cancer defense

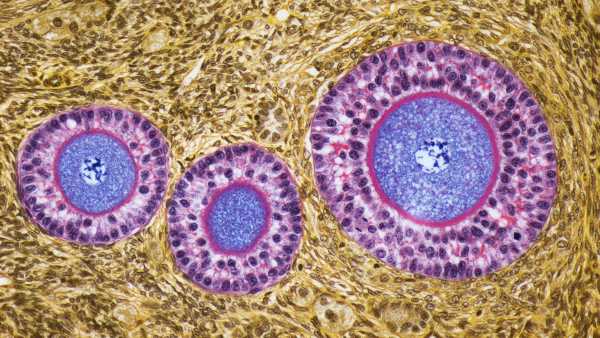

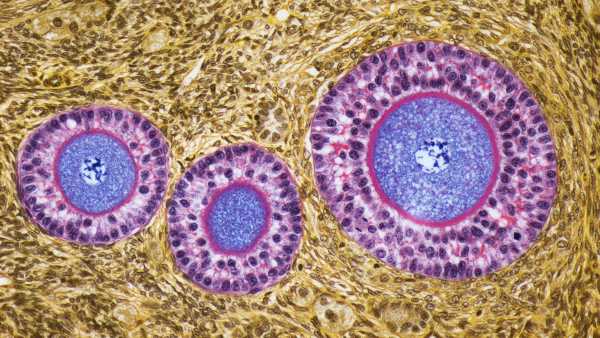

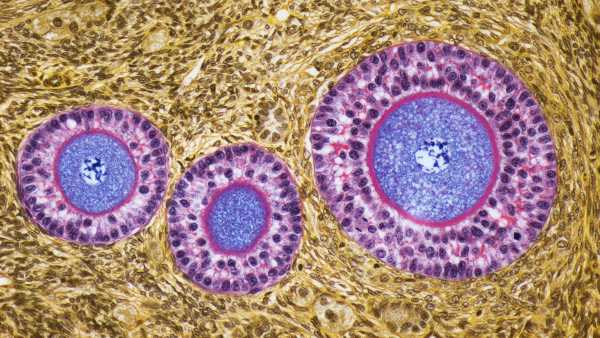

Wholesome hair development relies upon a population of stem cells that is constantly renewing itself inside of the hair follicle. A minute compartment within the follicle includes supplies of melanocyte stem cells — predecessors to the cells generating the melanin pigment, which gives hair its color.

“Each hair cycle, these melanocyte stem cells will split and create some matured, separated cells,” articulated Dot Bennett, a cell expert at City St George’s, University of London who had no association with the study. “These move downwards to the base of the hair follicle and start producing pigment to nourish the hair.”

Graying takes place when these cells can no longer produce ample pigment to entirely color each strand.

“It’s a kind of fatigue referred to as cell senescence,” Bennett clarified. “There’s a restriction to the total number of splits that a cell is able to proceed through, and it gives the impression of being an anti-cancer strategy to discourage unexpected genetic faults procured over time from multiplying uncontrollably.”

Whenever the melanocyte stem cells get to this “stemness checkpoint,” they discontinue splitting, leading to the follicle no longer possessing a source of pigment with which to color the hair. Typically, this unfolds in older age when the stem cells naturally reach this limit. However, Emi Nishimura, a professor of stem cell age-related medicine, along with her peers at the University of Tokyo were interested in the manner in which this same strategy functions as a response to DNA impairment — a crucial catalyst for cancer development.

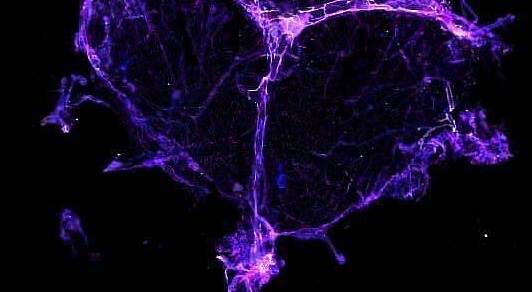

Through mouse studies, the team employed a mixture of methods to track the advancement of distinct melanocyte stem cells all through the hair cycle subsequent to their being subjected to differing detrimental environmental scenarios, including ionizing radiation and cancer-causing compounds. Remarkably, they determined that the kind of impairment swayed the way the cell reacted.

You may like

-

We might ultimately grasp stress-induced hair thinning

-

High-fiber nutrition may ‘restore’ immunity cells that combat cancer, study shows

-

Could older eggs be ‘restored’? A novel method might clear a path to treatments that prolong fertility

Ionizing radiation triggered the stem cells to distinguish themselves and ripen, and ultimately switched on the biochemical course liable for cell senescence. As a result, the melanocyte stem cell supplies were promptly used up over the hair cycle, thus terminating the creation of more mature pigment cells and bringing about gray hair.

Simultaneously, through fundamentally switching off cell division, this senescence course stopped the mutated DNA from being passed down to a new wave of cells, thereby reducing the chances of those cells creating cancerous growths.

Contact with chemical carcinogens — such as 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), a tumor instigator commonly utilized in cancer research — seemed to avoid this protective strategy. As opposed to switching on senescence, it toggled on a rival cellular course.

RELATED STORIES

—Can stress cause hair to turn gray?

—Is it possible to reverse gray hair?

—What causes hair to turn gray?

This other chemical order blocked cell senescence in the team’s mouse studies, enabling the hair follicles to sustain their stem cell supplies in addition to the capacity to create pigment, even following DNA destruction. That signified that the hair kept its color, but over the long haul, the unchecked multiplication of damaged DNA contributed to tumor development and cancer, the team stated in a report.

These discoveries reveal that one and the same stem cell population is able to come to different ends according to the category of stress they are subjected to, as mentioned by lead study writer Nishimura in the statement. “It recasts hair graying and melanoma [skin cancer] not as separate occurrences, but as branching consequences of stem cell stress replies,” Nishimura incorporated.

The subsequent measure will be to apply this insight to human hair follicles, to ascertain whether these observations in mice transition over to people, Bennett observed.

Disclaimer

This article is purely intended for informative purposes, serving exclusively as guidance and not for use as medical advice.

Victoria AtkinsonSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Victoria Atkinson acts as an independent science journalist, putting emphasis on chemistry and its link with the natural and constructed worlds. Currently situated in York (UK), she previously served as a science content creator at the University of Oxford, subsequently filling a role as a member of the Chemistry World editorial personnel. Following her transition to freelance work, Victoria has broadened her focal point to delve into subjects spanning the sciences, furthermore collaborating with Chemistry Review, Neon Squid Publishing, and the Open University, among others. She possesses a DPhil in organic chemistry attained from the University of Oxford.

Show More Comments

You are required to confirm your displayed name before commenting

Please log out before logging in once more, which will then prompt you to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

We might ultimately grasp stress-induced hair thinning

High-fiber nutrition may ‘restore’ immunity cells that combat cancer, study shows

Could older eggs be ‘restored’? A novel method might clear a path to treatments that prolong fertility

Aging and inflammation might not necessarily occur at the same time, as one study indicates

‘Chemo brain’ might be from damage to the brain’s discharge infrastructure

Heart attacks are less dangerous during the evening hours. Moreover, this might hold the key for handling them.

Latest in Ageing

Aging and inflammation might not necessarily occur at the same time, as one study indicates