Some researchers posit that “inflammaging,” a particular mechanism, contributes to the drop in the immune system’s function as individuals grow older. However, a recent analysis brings up pertinent inquiries.(Image credit: Westend61 via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 4Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

A fresh investigation aids in clarifying why certain immunizations, such as those targeting COVID-19 and the flu, exhibit diminished efficacy in mature individuals as compared to younger counterparts — and it could notably change how we comprehend the aging process.

Ordinarily, experts have connected the weakened immunization response detected in older individuals to a deterioration in the immune system as time passes. Numerous individuals have indicated that consistent, slight immune system activation — an occurrence termed “inflammaging” — is a main factor in this weakening.

Nonetheless, a new analysis contrasting the immune systems of older versus younger individuals identified no steady upticks in the biological indicators of inflammation linked to growing older. Alternatively, it seems that the passage of time modifies T cells — critical immune cells supporting a certain kind of white blood cell, known as B cells, to generate protective antibodies in response to viral invaders and vaccinations.

You may like

-

Slaying ‘zombie cells’ in blood vessels could be key to treating diabetes, early study finds

-

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

-

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

The conclusions, appearing Oct. 29 in Nature, intimate that inflammation might not be as vital to the process of getting older as previously assumed.

“We consider that inflammation is stimulated by a factor separate from simply the age of a person,” according to Claire Gustafson, an assistant investigator at the Allen Institute for Immunology and one of the leading contributors to the analysis, within a declaration.

Alan Cohen, an associate professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University who studies aging and inflammation, stated that these recent conclusions back a more finely differentiated understanding of “inflammaging.”

The concept suggesting that inflammation builds with age “might be statistically verifiable in industrialized groups,” according to Cohen, who was not linked to the investigation. “Nonetheless, it won’t hold true across the board, nor in every group,” he relayed to Live Science.

Cohen advised caution, indicating that all participating individuals in the current investigation were taken from Palo Alto, California, and Seattle — both locations characterized as highly industrialized. Pointing to considerable variations in inflammation seen among adult populations from countries like Italy, Singapore, Bolivia and Malaysia, he mentioned the possibility that these conclusions might not apply consistently across various environments.

“I surely wouldn’t interpret this as, ‘Oh look, now they’ve conclusively demonstrated that inflammation remains static with age,'” Cohen clarified. “I would consider it more as, here’s a scenario with a population that doesn’t appear to be going through the common changes we had generally come to anticipate.”

T cell modifications are not incited by inflammation

To enhance how older individuals respond to vaccinations, Gustafson and fellow researchers assessed the ways in which T cells are impacted by aging.

You may like

-

Slaying ‘zombie cells’ in blood vessels could be key to treating diabetes, early study finds

-

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

-

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Initially, they matched younger individuals (spanning 25 to 35 years of age) against an older cohort (spanning 55 to 65 years of age, or those at what researchers identify as being on the “cusp of aging”). For a period of two years, researchers kept tabs on 96 healthy volunteers within those age ranges, taking blood samples from each subject somewhere between eight to ten times, also tracking their immune systems before as well as after their seasonal flu shots. Following that, they developed the study to incorporate a further group of 234 adults aged between 40 to over 90.

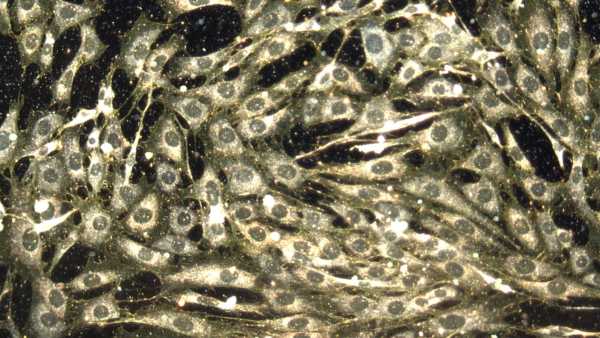

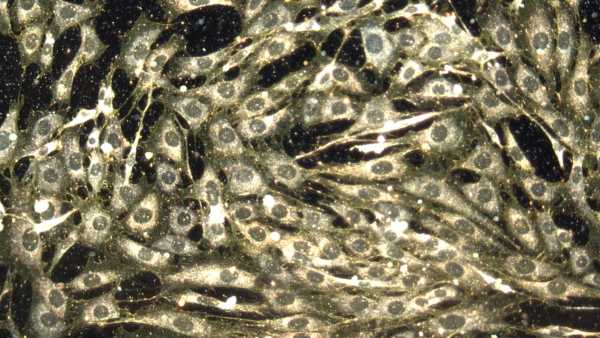

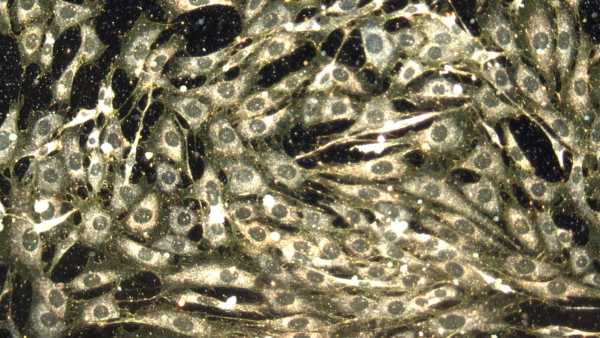

To scrutinize the immune system across all these groups, the team employed single-cell RNA sequencing; this facilitated an examination of the genetic material categorized as RNA found inside each immune cell. RNA mirrors which particular proteins a cell may be producing at a specific moment. The team also made use of high-dimensional plasma proteomics, charting proteins moving within blood, along with spectral flow cytometry, that determined the identity and the total count of immune cells depending on their “fingerprints” at a molecular scale.

The researchers noticed particular distinctions within memory T cells — immune cells that “memorize” past infections, helping the body to respond with greater speed when encountering a pathogen once more.

Inside older adults, escalating quantities of memory T cells transition to a condition altering the manner in which they deal with perceived danger — through modifying the way they connect with B cells. Whenever memory T cells cease functioning as expected, B cells suffer from reduced capability in generating protective antibodies in reaction to infections or immunizations, the analysis stated. Simultaneously, young adults’ memory T cells seemed adept in mounting a fast reaction as well as accelerating the predicted antibody reply.

Evidently, such immune changes take place separately from inflammation together with latent virus infections, that linger within the body after the initial infection and might become inactive, thus creating no blatant symptoms. Infections resulting from such viruses, like cytomegalovirus (CMV), commonly receive blame for weakening the immune system as age increases. Nevertheless, the analysis discovered that people under 65 who, at some phase within their life, encountered a CMV infection did not exhibit faster immune aging markers, neither elevated levels of inflammatory proteins.

RELATED STORIES

—Biological aging may not be driven by what we thought

—’If you don’t have inflammation, then you’ll die’: How scientists are reprogramming the body’s natural superpower

—’Aging clocks’ tell you how much ‘older’ you are than your chronological age. How do they work?

Cohen suggests lingering wariness regarding conclusions put forth by the study authors, mentioning that most substantial alterations to the immune system are likely to take place after age 65. “If an inflammation alteration fails to appear contrasting a 25 to 35 age bracket against a 55 to 65 age bracket, would that genuinely be because inflammation doesn’t fluctuate across time, or merely stemming from not being old enough to observe anything?” he wondered.

The researchers expressed optimism that such conclusions may eventually guide scientists in designing immunizations offsetting immune alterations connected to age, therefore enhancing protection for older individuals. They likewise believe the findings might prove beneficial in crafting therapies recovering immune function as age increases.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

TOPICSvaccines

Clarissa BrincatLive Science Contributor

Clarissa Brincat is a freelance writer specializing in health and medical research. After completing an MSc in chemistry, she realized she would rather write about science than do it. She learned how to edit scientific papers in a stint as a chemistry copyeditor, before moving on to a medical writer role at a healthcare company. Writing for doctors and experts has its rewards, but Clarissa wanted to communicate with a wider audience, which naturally led her to freelance health and science writing. Her work has also appeared in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Slaying ‘zombie cells’ in blood vessels could be key to treating diabetes, early study finds

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Heart attacks are less harmful at night. And that might be key to treating them.

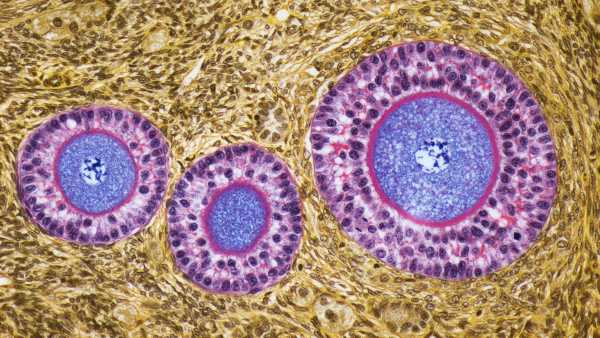

Could aging eggs be ‘rejuvenated’? New tool may help pave the way to fertility-extending treatments

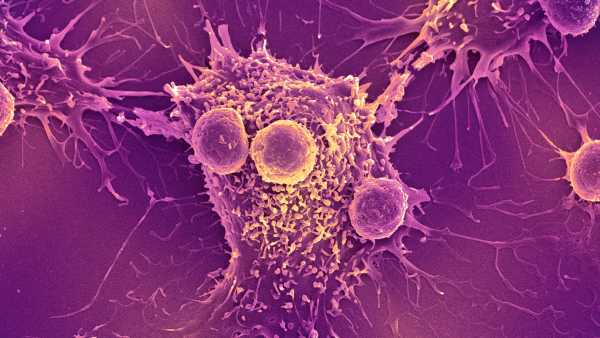

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines can trigger the immune system to recognize and kill cancer, research finds

Latest in Ageing