The U.S. Defense Department will not complete the distribution of critical satellite weather data on Friday as previously planned.

A month ago, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a notice of change that was supposed to go into effect July 1. Then NOAA said the changes would be delayed by one month until Thursday.

In an update released Wednesday, plans for the phased completion were delayed by one year.

“The Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center (FNMOC) has indicated its intent to continue distributing Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) data beyond July 31, 2025,” the update said. “There will be no disruption to DMSP data.”

As peak hurricane season approaches, forecasters from the National Weather Service, the National Hurricane Center, the media, private meteorologists and weather observers have expressed concerns about the lack of satellite imagery.

“A crisis has been averted,” Michael Lowry, a meteorologist with the National Hurricane Center's Storm Surge Division, wrote on Blue Sky, adding that it “means our hurricane forecasting tools will remain operational.”

A U.S. Space Force spokesman said the satellites and instruments are operational and the Defense Department will continue to operate them.

A UN Navy spokesman told ABC News that there had been a “phased out of data transmission as part of the Department of Defense modernization,” but that plan was shelved after receiving feedback and finding “a way to meet the modernization goals while continuing to stream data until the sensor fails or the program officially ends in September 2026.”

The Pentagon has used satellites to monitor the atmosphere and oceans for 40 years. The dedicated microwave imaging and sounding sensors on three DMSP satellites will be turned off.

Kim Wood, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Arizona, told Scientific American that the satellites detect a variety of wavelengths of light, including visible, infrared and microwaves.

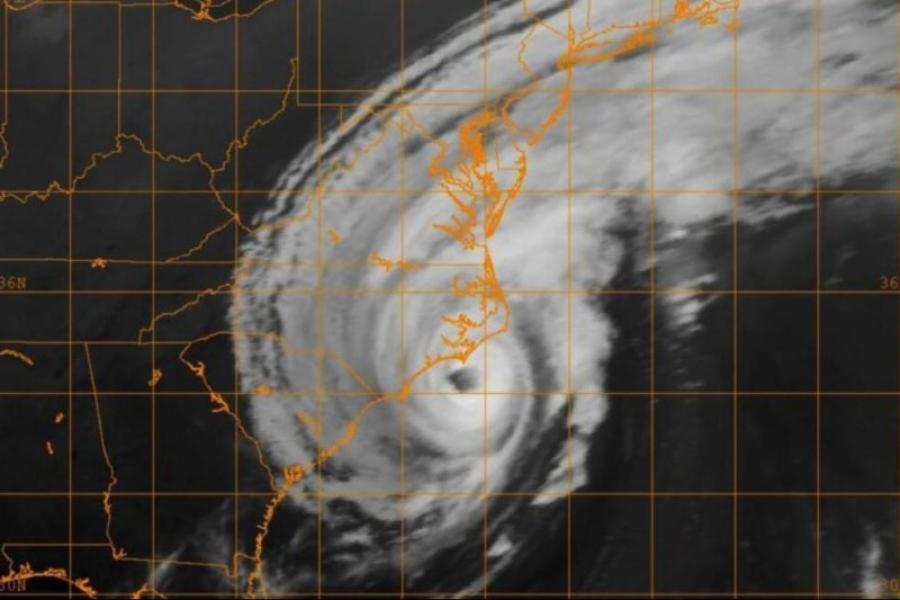

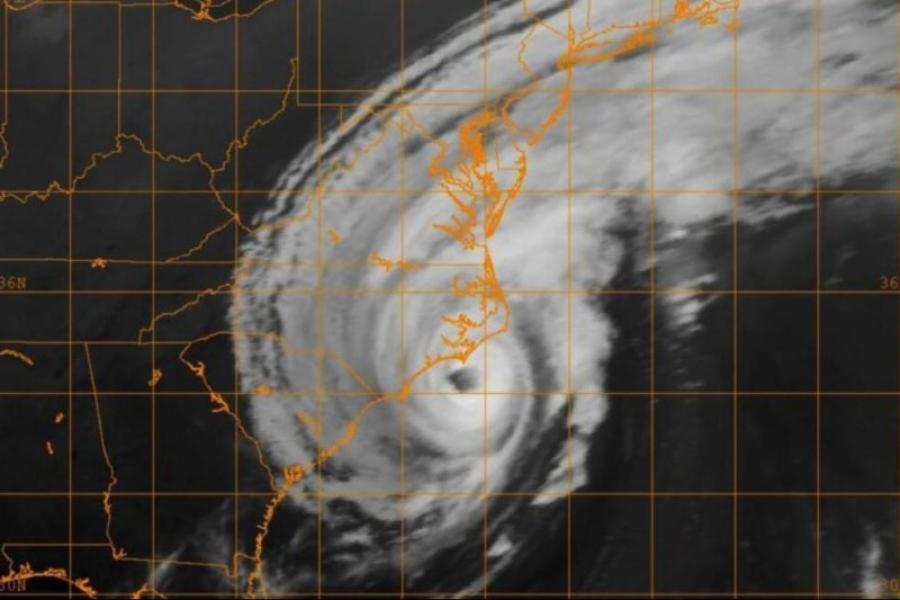

Microwaves are used to monitor hurricanes, Wood said, “because the waves are so long they penetrate the top layers of clouds,” and help scientists understand the inner workings of storms, especially those that occur at night.

With real-time data, hurricane experts can determine where the center of a storm is forming, which in turn allows them to predict its likely path, including its path to land.

They can spot when a hurricane begins to form a new eye, which helps gauge its intensity. This was seen earlier this month during Hurricane Erik in the Pacific Ocean.

The Navy uses this data to track the status of its ships.

“It's not a funding cut,” Mark Serrese, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, a government-funded research center in Colorado, told NPR. “There are cybersecurity issues. That's what we've been told.”

Yet the Trump administration is cutting funding for federal weather agencies.

The National Hurricane Center, which is run by NOAA, did not expect less accurate forecasts.

“NOAA's data sources are capable of providing a comprehensive set of up-to-date data and models that provide the high standard of weather forecasting that the American people deserve,” Kim Doster, NOAA's communications director, told NPR. NOAA and NASA also operate satellites used for forecasting.

The hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30. There are currently six hurricanes in the Pacific Ocean and three in the Atlantic.

Sourse: www.upi.com