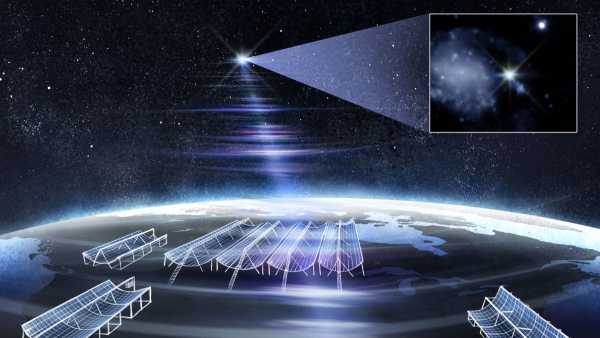

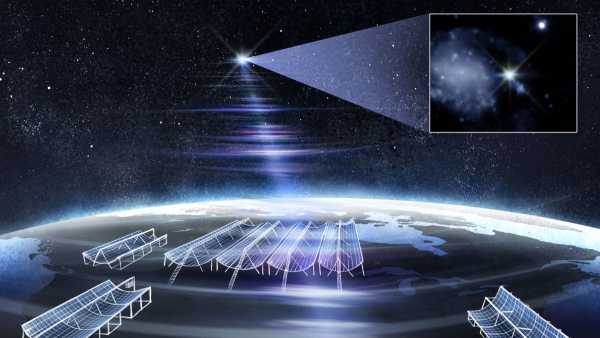

An image of the ultra-luminous radio burst RBFLOAT erupting over Canada's CHIME radio telescope. (Image credit: NASA/ESA/CSA/CfA/P. Blanchard et al.; Image processing: CfA/P. Edmonds)

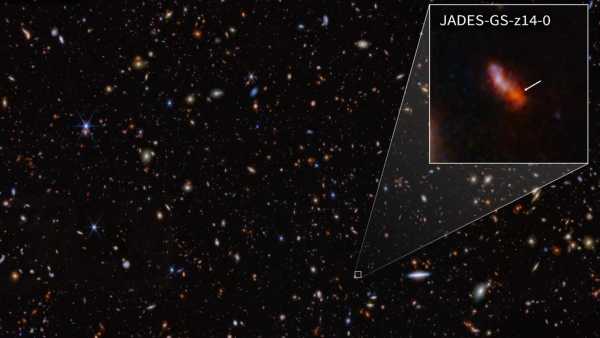

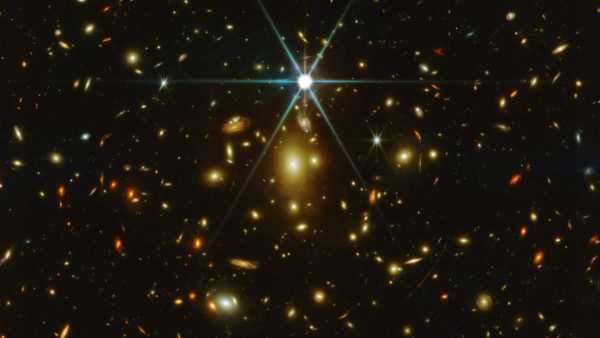

For the first time, scientists have used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to study the origin of a strange, record-breaking radio signal that flashed past Earth earlier this year.

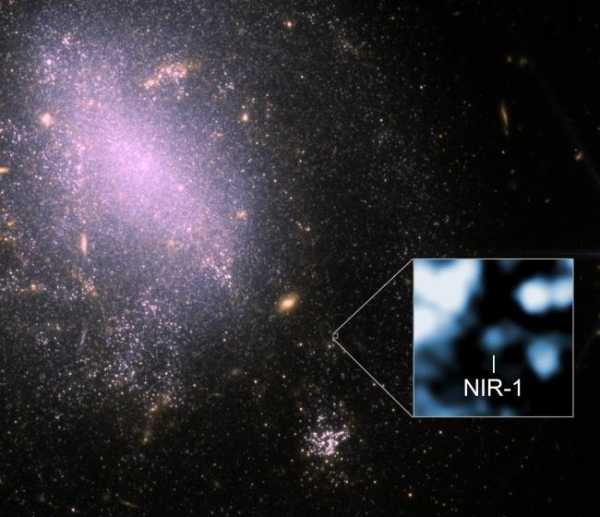

By tracking a bright radio burst to the edge of a galaxy about 130 million light-years from Earth, the researchers used JWST's infrared sensor to identify a powerful burst of energy coming from a large, old star that may be the source of the strange signal. The team also zoomed in on individual stars clustered nearby, providing an unprecedentedly clear picture of the burst's original environment.

The results, described in two papers published August 21 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, could mark a turning point in the study of fast radio bursts (FRBs), which have until now been extremely difficult to trace back to their source galaxies, let alone the specific star systems that produced them.

You may like

-

Strange New Object Sends Radio Signals to Earth Every 44 Minutes

-

Scientists Discover Fast-Spinning 'Unicorn' Object That Defies Physics

-

The James Webb Telescope has broken its own record by discovering the most distant galaxy known in the Universe.

“The high resolution of JWST allows us to resolve individual stars around FRBs for the first time,” said Peter Blanchard, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University and lead author of one of the papers. “This opens the door to identifying the types of stellar environments that can produce such powerful flares, especially since rare FRBs are detected in such detail.”

“Floating” new opportunities

As their name suggests, fast radio bursts are incredibly short pulses of radio energy. They often last only a few milliseconds, but in that time they emit more energy than the Sun does in several days.

Since their discovery in 2007, scientists have detected more than 1,000 fast radio bursts (FRBs) shooting out from all corners of the sky. But the pulses’ ultra-short durations make them difficult to study. Many of the strange signals seem to repeat, but some do not. There are several theories about what causes FRBs, the most likely being magnetars — the rapidly spinning, highly magnetized shells of dead stars called neutron stars. But even that is unclear.

In March, astronomers at the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME), a collection of more than 1,000 radio receivers studying fast radio bursts (FRBs), detected the brightest radio burst ever recorded at the site. The team has officially named the powerful burst FRB 20250316A, and dubbed it “RBFLOAT” (for “brightest radio burst of all time”).

The burst’s extreme brightness suggested that the FRB originated relatively close to the Milky Way, the researchers said, making it an ideal target for CHIME’s new Outrigger Array, which spans North America from California to British Columbia. By studying the powerful FRB from multiple vantage points, the researchers pinpointed its location in the galaxy NGC 4141, located inside the Big Dipper, and then further narrowed down the burst’s origin to a region of space just 45 light-years across. (For comparison, our own Milky Way galaxy spans about 100,000 light-years.)

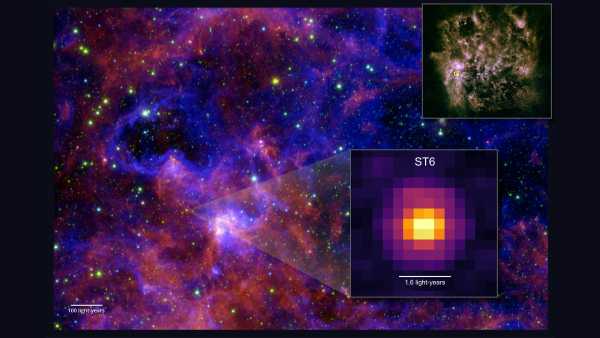

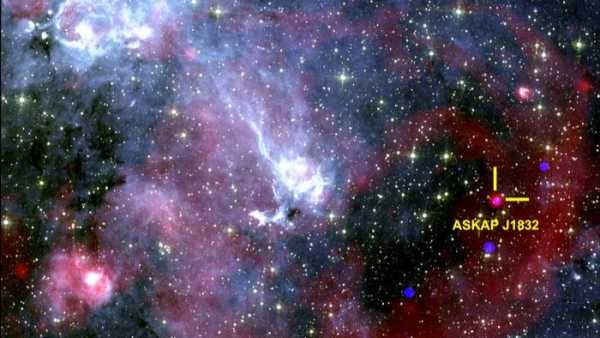

An infrared image of the galaxy NGC 4141 taken by the James Webb Space Telescope shows a fast radio burst (FRB) named FRB 20250316A. The object, designated NIR-1, is thought to be the likely source of the ultraluminous burst.

“The accuracy of this localization… is comparable to detecting a quarter from 100 kilometers [62 miles] away,” Amanda Cook, a research fellow at McGill University and lead author of the second paper, said in a statement.

After CHIME’s initial detective work, the team turned to the powerful JWST, which zoomed in on the narrow region of space where the RBFLOAT originated. The telescope not only captured a burst of infrared energy in the same location where the FRB was detected, but also examined individual stars in the surrounding area to characterize the environment from which the radio burst emanated.

“This may be the first FRB-related object discovered in another galaxy,” Blanchard said in another statement.

related stories

— The James Webb telescope has stunned scientists with a picture of an ancient galaxy coming back to life.

— Dry ice geysers erupt on Mars when spring comes to the Red Planet.

— James Webb and Hubble telescopes team up to solve 'impossible' planet mystery

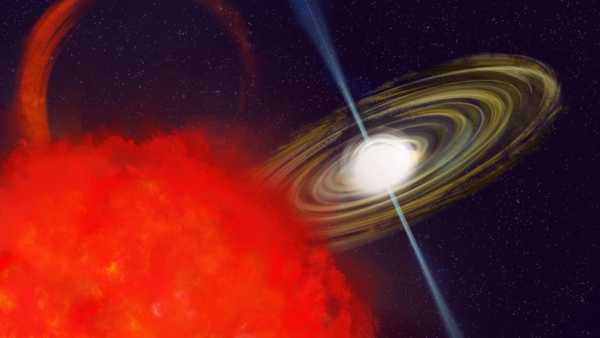

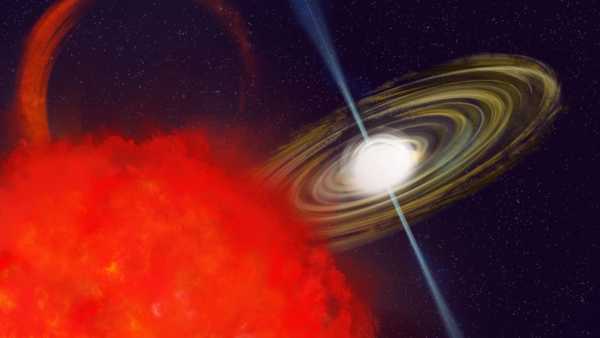

The JWST data revealed that the infrared object is either a red giant (a star that has ballooned toward the end of its life) or a massive, middle-aged star many times more massive than the Sun. Although neither type of star is a potential source of fast radio bursts (FRBs), it is likely that the infrared object is orbited by an unseen companion star, such as a neutron star that is belching energy. If so, the companion star could be siphoning material from its larger parent star, which could trigger the bright radio burst.

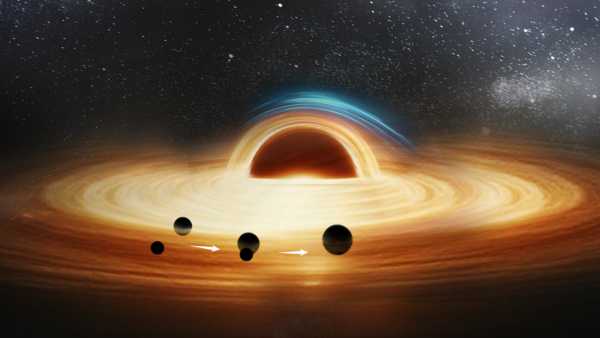

By studying the surrounding environment, which is teeming with young but massive stars, the team also came up with a second hypothesis: that one of the large stars in the cluster had already collapsed into a magnetar, which could easily emit an FRB but would be too faint to be seen directly by JWST.

“Whether or not the star connection is real, we've learned a lot about the origin of the outburst,” Blanchard said. “If a binary star system isn't the answer, our work points to an isolated magnetar as the cause of the FRB.”

Beyond RBFLOAT, this study shows that the newly upgraded CHIME experiment can localize elusive fast radio bursts with unprecedented precision, and that JWST is emerging as a powerful partner in the search for these enigmatic cosmic phenomena. Further tracking of fast radio bursts to their origin will not only help solve one of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics, but could also shed new light on stellar dynamics, revealing how different stars behave throughout their bright but turbulent lives.

TOPICS James Webb Space Telescope

Brandon SpectorSocial Media Navigation Content Editor

Brandon is the Space/Physics Editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation, and elsewhere. He holds a BA in Creative Writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in Journalism and Media Arts. He enjoys writing about space, the geosciences, and the mysteries of the universe.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be prompted to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

Strange New Object Sends Radio Signals to Earth Every 44 Minutes

Scientists Discover Fast-Spinning 'Unicorn' Object That Defies Physics

The James Webb telescope has broken its own record by discovering the most distant galaxy known in the Universe.

Astronomers have discovered the most powerful cosmic explosions since the Big Bang

'People thought it was impossible': Scientists observe 'cosmic dawn' light for the first time in history using a telescope on Earth.

James Webb Space Telescope Finds Tentacle-Like 'Jellyfish' Galaxy Floating in Deep Space. Astronomy News

A solar tornado rages across the Sun, spewing out a giant plume of plasma.

Uranus Has a New Hidden Moon Discovered by the James Webb Space Telescope

Where can you see the total lunar eclipse on September 7, the “blood moon”?

Scientists believe they have discovered the first known triple black hole system in the Universe and then watched it die.

Rare 'Black Moon' Rising This Weekend: What Is It and What Can You See?

Oops! Earendel, the most distant star ever discovered, may not be a star at all, the James Webb Telescope has revealed. Latest news

'We never had concrete evidence': Archaeologists discover Christian cross in Abu Dhabi, proving 1,400-year-old settlement was once a monastery

Surprising results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater are formed in the stratosphere.

Asteroids Bennu and Ryugu May Be Long-Lost Siblings, JWST Hints

The first Americans had Denisovan DNA. And it may have helped them survive.

How does the tubal ligation procedure work?

In September we will have an “equinox eclipse” LATEST ARTICLES

1'We never had concrete evidence': Archaeologists discover Christian cross in Abu Dhabi, proving 1,400-year-old site was a monastery

Live Science is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web Notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com