A mosasaur, an ancient reptile that lived during the Mesozoic, might have laid the newly described fossil egg found in Antarctica.

A 68 million-year-old egg the size of a football — the largest soft-shelled egg on record and the second largest egg ever discovered — might belong to a mosasaur, a reptilian sea monster that lived during the age of dinosaurs in what is now Antarctica, a new study finds.

If true, this would be the only mosasaur egg on record, according to the study, published online yesterday (June 17) in the journal Nature.

“There’s no known egg like this,” study senior researcher Julia Clarke, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin), told Live Science. “This egg is exceptional in both its size and its structure.”

Chilean researchers found the eggs-traordinary fossil in a seasonal stream in 2011, about 660 feet (200 meters) away from the remains of 33-foot-long (10 m) Kaikaifilu hervei, a large mosasaur unearthed on Seymour Island, Antarctica, said study co-researcher David Rubilar-Rogers, a paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN) in Santiago, Chile. Despite the egg’s proximity to the mosasaur, however, “the identity of the animal that laid the egg is unknown,” the researchers wrote in the study.

“Although we weren’t clear on what it was, the strangeness of its shape was enough to collect it and take it to camp,” Rubilar-Rogers told Live Science in an email translated from Spanish. The fossil was so bizarre, the team called it “The Thing,” after the 1982 sci-fi movie based in Antarctica, which the paleontologists bravely watched when they were stuck in their tents due to bad weather, study co-researcher Rodrigo Otero, a paleontologist at the University of Chile in Santiago, told Live Science.

The Thing sat in the MNHN until 2018, when Clarke visited and struck up a conversation with Rubilar-Rogers about how Antarctica didn’t have any known fossilized eggs. On a hunch, he showed her The Thing. “To me, it looked exactly like a deflated football,” Clarke recalled.

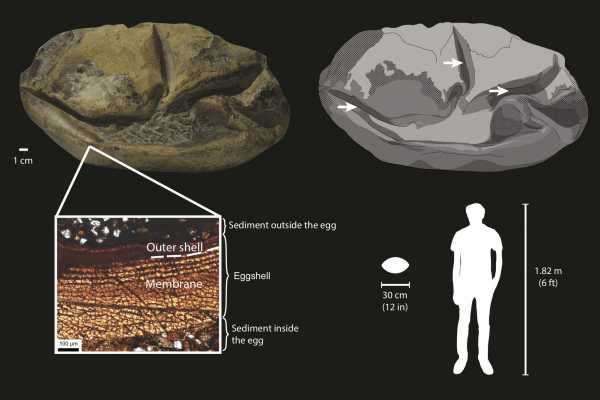

The following analysis, however, revealed it was an exceptional find. At about 11 inches by 8 inches (29 by 20 centimeters), it’s second in size only to the egg of the extinct Madagascan elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus). It’s also the only known fossil egg ever found in Antarctica.

Image 1 of 6

The fossil egg is the largest known soft-shelled egg in the world. Gallery: An egg, possibly from a mosasaurImage 2 of 6

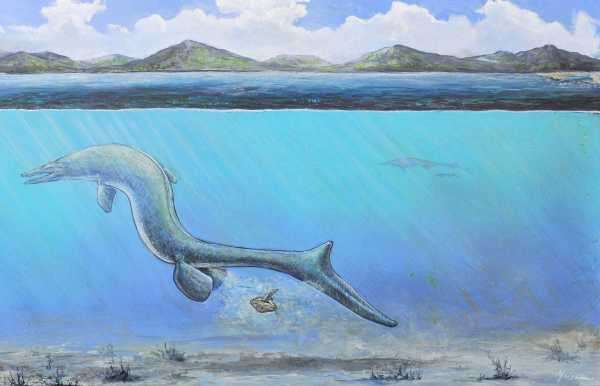

This is how the mosasaur might have laid the egg. Image 3 of 6

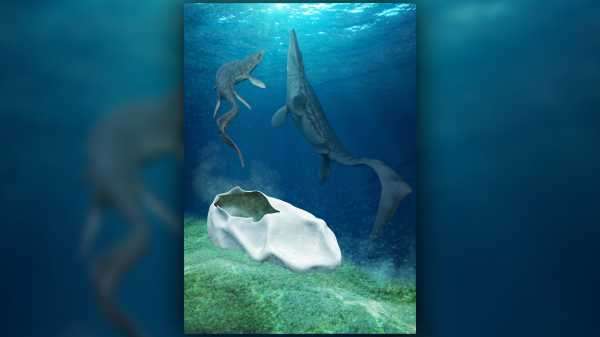

The soft-shelled egg filled with sediment (and an ammonite) before it fossilized. Image 4 of 6

The mosasaur might have laid the egg underwater (as some sea snakes do today) or on land (as modern sea turtles do). Image 5 of 6

A mosasaur mother laying an egg, next to another mosasaur baby that just hatched out of its egg. Fossil egg galleryImage 6 of 6

An illustration of the enormous mosasaur next to her tiny egg and baby. Is it really a mosasaur?

The newfound egg, dubbed Antarcticoolithus bradyi (or “delayed Antarctic stone egg” in Greek), pushes the limits of how large scientists thought soft-shelled eggs could grow. In contrast to the hard-shelled elephant bird’s egg — which was five times thicker than this one — A. bradyi has a thin eggshell that lacks pores. These features also set A. bradyi apart from most ancient dinosaur eggs.

“It is from an animal the size of a large dinosaur, but it is completely unlike a dinosaur egg,” study lead researcher Lucas Legendre, a postdoctoral researcher at UT Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, said in a statement. “It is most similar to the eggs of lizards and snakes, but it is from a truly giant relative of these animals.”

Like lizards and snakes, mosasaurs fall into the Lepidosauria group. Though the baby that incubated within the egg is long gone (the team did find an ammonite inside of it, however), the team said there are clues that it was a mosasaur. For instance, there aren’t any known late Cretaceous Antarctic dinosaurs or pterosaurs large enough to have laid such a huge egg, Clarke said. But the remains of the contemporary K. hervei are nearby.

An analysis of 259 living lepidosaur species and their eggs suggested that A. bradyi belonged to a mother measuring at least 23 feet (7 m) long, not including the tail. It’s possible that during the late Cretaceous this area of Antarctica was a nursery, as paleontologists have also found fossils of baby mosasaurs and plesiosaurs there, along with adult remains.

Dinosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs, too

The soft-shelled egg finding is “pretty spectacular,” said Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of dinosaur paleobiology at the University of Calgary in Canada, who wasn’t involved in the research. “Soft-shelled eggs consist almost entirely of membranes, so these soft tissues are quite fragile and destructible. Because of this, for many years we thought that fossilization of such eggs was nearly impossible.”

Until now, many researchers didn’t think that mosasaurs laid eggs, the authors noted. If A. bradyi is a mosasaur egg, it would “represent one of the first known instances of live birth in an ancient, extinct species of the snake and lizard family,” Zelenitsky told Live Science in an email.

Zelenitsky is the senior researcher on another study also published in Nature yesterday suggesting that the first dinosaur eggs had soft shells. Their conclusion is based on the discovery of fossilized soft eggshells from the horned dinosaur Protoceratops, which lived during the Cretaceous period, and the Triassic period sauropodomorph Mussaurus.

Image 1 of 3

A clutch of fossilized Protoceratops eggs, which were found in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia at Ukhaa Tolgod. Dinosaur soft-shelled egg galleryImage 2 of 3

The preserved Protoceratops remains include six embryos that contain nearly complete skeletons. Image 3 of 3

A fossilized egg was laid by Mussaurus, a plant-eating dinosaur that grew up to 20 feet (6 meters) in length and lived between 227 million and 208.5 million years ago in what is now Argentina.

Given that Zelenitsky’s study found soft-shelled dinosaur eggs, perhaps A. bradyi actually came from dinosaur eggs laid on land that then washed out to sea, two Swedish researchers wrote in an accompanying opinion piece in Nature.

Zelenitsky, too, thought that “the new egg looks a lot like the soft-shelled eggs of dinosaurs. Perhaps an analysis comparing the soft tissue of A. bradyi with those of other reptile eggs could shed light on what kind of animal laid it, she said.

Sourse: www.livescience.com