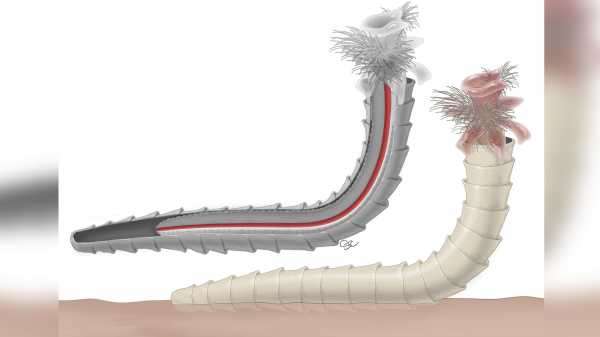

An artist’s interpretation of the ancient cloudinomorph, with the guts shown in red. Artwork by Stacy Turpin Cheavens, University of Missouri.

Tiny, tubular fossils found in Nevada may contain the oldest digestive tracts ever found.

The fossils date back more than half a billion years, to the late Ediacaran period. That makes them about 30 million years older than the next-oldest fossilized guts on record. More important than their age, though, is that these fossilized guts could finally pinpoint the identity of one of the most widespread types of animals before the Cambrian explosion, the rapid diversification of life that occurred soon after the end of the Ediacaran.

The fossils come from Nye County, in southern Nevada. They date to between 550 million and 539 million years ago. This was the end of the Ediacaran, the period in which the earliest multicellular complex life arose. Life at that time was bizarre and hard to classify by modern standards; most fossils of these organisms look like fronds, tubes or vaguely round bags.

Among the most common fossils from the late Ediacaran are a group called cloudinomorphs. Their fossils are found worldwide, Schiffbauer told Live Science, and they look like little tubes. Many of these organisms had mineralized shells made of calcium carbonate, just like seashells today. But paleontologists haven’t been able to figure out what these cloudinomorphs were. They have proposed everything from sponges to algae, Schiffbauer said, but the leading hypotheses are that cloudinomorphs were either cnidarians, like today’s coral, or annelids, like modern tube worms.

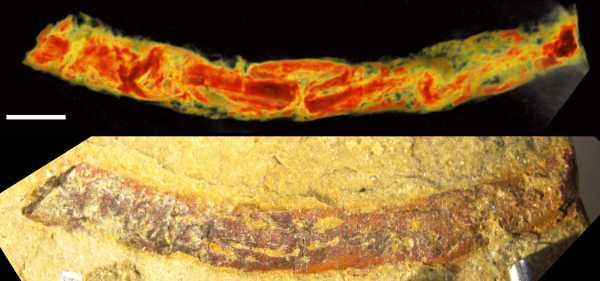

The Nevada fossils offered a chance to answer this question. Unlike in other locations around the world, the cloudinomorph fossils from Nevada are still hollow. After the cloudinomorphs died, their soft tissues were typically preserved by pyritization, a process that creates a shiny pyrite (fool’s gold) cast of the living creature. For whatever geochemical reason, the pyrite did not completely fill the tubes of the Nevada cloudinomorphs, allowing researchers to see the soft tissues inside.

Study co-author Tara Selly, a paleontologist at the University of Missouri, found the first of these fossilized guts. She was learning to use the university’s new X-ray microscope and picked a cloudinomorph fossil to practice with.

“It turns out that the first one I looked at had a gut in it,” Selly told Live Science.

Early animal

The ancient guts can be seen in red in the 3D rendering (top) of one of the cloudinomorph specimens (bottom)

As the researchers studied more fossils, they found more and more tubular guts within them, many better preserved than the first specimen. They studied the mineral structure of the preservation and found that it matched what is seen in gut preservation from more-recent Cambrian fossils.

Identifying the soft tissue as a gut seems like a plausible explanation for what the researchers saw, though more work will be needed to confirm that the tissue is really from the gut of the organism, said Shuhai Xiao, a geobiologist at Virginia Tech who studies late Ediacaran fossils and was not involved in the current research. “If this interpretation is correct, that has some really interesting implications,” Xiao told Live Science.

The primary one is that the gut looks like a tube, not like a sack with one open end. Cnidarians, such as corals, have a gut with one opening that acts as both a mouth and an anus. Annelids, like tube worms, have two separate openings: one mouth and one anus. The latter is a more advanced arrangement that allows for the evolution of a segmented digestive system like the one in humans, Xiao said.

“A tube would tell us that it’s probably a worm,” Schiffbauer said.

That’s an exciting finding because cloudinomorphs survived a mass extinction at the end of the Ediacaran. The causes of this mass extinction are fuzzy, but a widespread lack of oxygen in Earth’s oceans may have smothered most Ediacaran life-forms.

“They’re holdovers,” Schiffbauer said of cloudinomorphs. They are also a thread that could potentially link the alien world of the Ediacaran to recognizable animals that eventually evolved into the life Earth hosts today.

“We’re trying to work toward understanding that time frame a bit better as the dawn of animals,” Schiffbauer said.

The findings appear today (Jan. 10) in the Journal Nature Communications.

Sourse: www.livescience.com