The Triassic period beast Tanystropheus hydroides had a neck that was three times the length of its torso.

A Triassic-aged sea monster with “a very long broomstick for a neck,” sharp curved teeth and a crocodile-like snout wasn’t a prima donna; rather, this reptile shared Pangaea’s coastal waters with another long- and stiff-necked beast — one that was so similar-looking, scientists used to think the two predators were the same species.

Now that it’s clear that these giraffe-like reptiles are two distinct species, scientists chose to name the larger of the two Tanystropheus hydroides, a nod to the hydra, the long-necked mythical sea monster of Greek antiquity. The smaller one kept the preexisting name, Tanystropheus longobardicus.

It’s rare for two animals with such peculiar necks — which were not just long but also fairly inflexible — to live in the same place simultaneously, the researchers said. But T. hydroides and T. longobardicus somehow found a way to coexist when they were alive about 242 million years ago, mainly by hunting different animals so they didn’t have to compete for food, according to an analysis of their teeth and earlier analyses of T. hydroides’ stomach contents.

“They had evolved to feed on different food sources with different skulls and teeth, but with the same long neck,” study lead researcher Stephan Spiekman, a former doctoral student at the University of Zurich’s Paleontological Institute and Museum in Switzerland, told Live Science in an email.

Paleontologists first described Tanystropheus in 1852, but have struggled since then to make sense of its strange anatomy. The Italian paleontologist Francesco Bassani (1853-1916) thought Tanystropheus was a flying reptile called a pterosaur, and that its long hollow neck bones were actually finger bones that supported its wings. This hypothesis was later debunked when scientists realized that the 20-foot-long (6 meters) reptile had a 10-foot-long (3 m) neck that was three times the length of its torso.

Smaller, 4-foot-long (1.2 m) fossil specimens found in the same Triassic period outcrops were thought to be juveniles of the same species, said study co-researcher Olivier Rieppel, the Rowe Family Curator of Evolutionary Biology at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Image 1 of 6

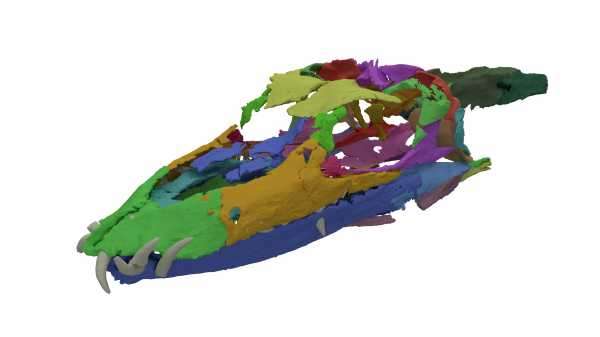

A CT scan showing the digitally resembled skull of Tanystropheus hydroides. Image 2 of 6

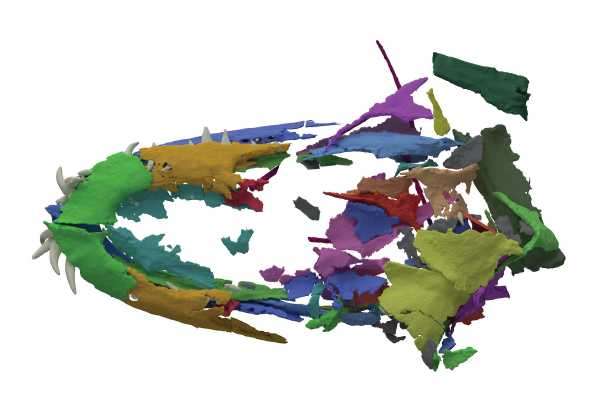

A CT scan of Tanystropheus hydroides’ skull before it was digitally reassembled. Image 3 of 6

This illustration shows the crocodile-like snout of Tanystropheus hydroides. Image 4 of 6

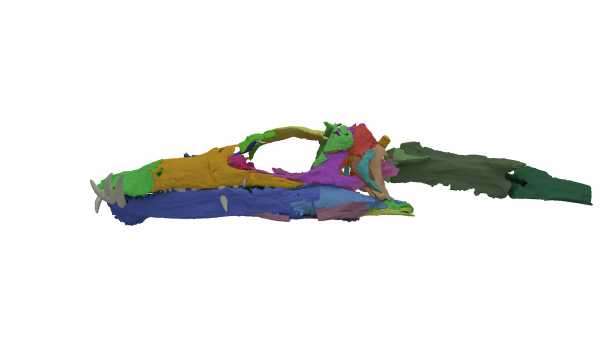

The digitally reassembled skull of Tanystropheus hydroides, as seen from the left side. Image 5 of 6

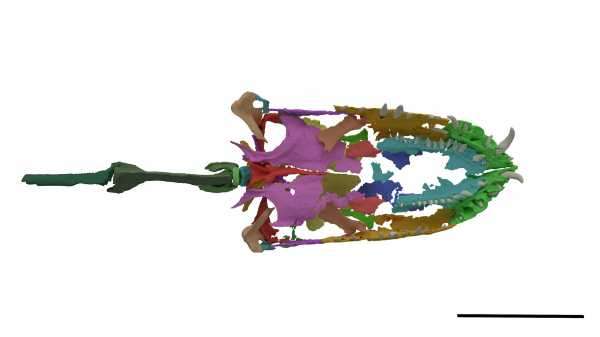

The ventral view (looking upward at the roof of the mouth) of the digitally resembled skull of Tanystropheus hydroides. Image 6 of 6

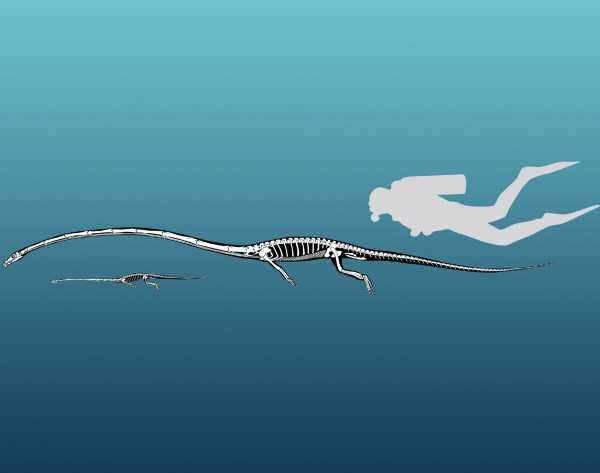

The smaller Tanystropheus longobardicus next to the larger Tanystropheus hydroides, swimming next to a diver for scale.

Curiously, these big and small reptiles each had only 13 elongated neck vertebrae, some of which were reinforced with extra bones known as cervical ribs, making their necks relatively stiff. In contrast, the Triassic long-necked reptile Dinocephalosaurus had upwards of 30 neck vertebrae, and the sauropod dinosaurs had up to 19 neck vertebrae. The additional vertebrae gave these animals more cervical flexibility than Tanystropheus had, Rieppel said.

“Why such a neck? That has always been the question,” Rieppel said. Some paleontologists thought it survived in spite of its neck. But the genus Tanystropheus, which includes several other long-necked species such as T. conspicuus and T. antiquus, did quite well for itself, surviving roughly 14 million years, from about 248 million to 234 million years ago. Soon, paleontologists began wondering whether Tanystropheus survived not in spite of, but because of its neck, Rieppel said.

Given that so many of these species had stiff, long necks, it’s likely that “this strange anatomy of Tanystropheus was ecologically much more versatile and adaptive than had previously been thought,” Rieppel said.

While it’s anyone’s guess exactly how the two Tanystropheus species used their necks, one idea is that it helped them hunt. Tanystropheus have small heads at the end of their long necks. “My best guess is that this would make this head quite difficult to see for its prey, especially in somewhat turbid water,” Spiekman said. “This way, Tanystropheus, both the small and large species, were able to approach their prey closely without getting spotted and without having to be particularly good swimmers.”

Once that prey was close enough, “it would simply snap at its prey to catch it,” Spiekman said. Or, maybe Tanystropheus had a fleshy lure that didn’t fossilize (soft tissues rarely do), but which helped it attract prey, much like how the snapping turtle uses its tongue as a lure, he said.

Stiff necks

Tanystropheus resembled a monitor lizard, “but with a very long broomstick for a neck,” said Spiekman, who will be a postdoctoral researcher at the Natural History Museum in London this October. However, many large Tanystropheus fossils are crushed, so they’re hard to decipher. Scientists couldn’t even agree if it was land dwelling or sea faring.

So, the researchers of the new study CT scanned the skull of a big Tanystropheus specimen from the Swiss-Italian border, which allowed them to assemble 3D digital images of its skull. The scientists also studied both creatures’ cranial anatomies, and they sliced through some of the fossilized bones of two smaller Tanystropheus individuals, so they could see the creatures’ growth rings, which are like the rings of a tree.

The researchers focused on the skulls because “other than size, there’s basically no difference in the skeleton between the two species,” Spiekman said. “But the skulls are, of course, very different as they are adapted to deal with different food sources.”

RELATED CONTENT

—In Images: Graveyard of ichthyosaur fossils in Chile

—Photos: Uncovering one of the largest plesiosaurs on record

—Image gallery: Ancient monsters of the sea

Tanystropheus had nostrils on top of its snout like a crocodile, suggesting it lived in the water. The larger T. hydroides was likely an ambush predator that waited for fish and squid-like animals to swim by before it grabbed them with its long, fang-like teeth. It’s still unclear whether the larger beast laid eggs on land, like a turtle, or had live births in the water like other Triassic reptiles, such as the ichthyosaur.

An analysis of the smaller Tanystropheus’ growth rings revealed that it was fully grown. Taken together with its unique skull anatomy and teeth (the smaller Tanystropheus had cone-shaped teeth while the larger one had crown-shaped chompers), the researchers concluded that the smaller Tanystropheus wasn’t a juvenile, but the separate species T. longobardicus.

Despite their shared long necks and habitats in Pangea’s Tethys Sea, these two Tanystropheus species had different lifestyles. The smaller T. longobardicus likely ate small shelled animals, such as shrimp, while the larger T. hydroides gulped down fish and squid.

“The neck of Tanystropheus looks very awkward to us,” Spiekman said. “But Tanystropheus was not a weird evolutionary ‘mistake,’ as was previously thought. Instead, it was in terms of evolution a very successful animal because of its neck, and not despite of it.”

The study was published online today (Aug. 6) in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sourse: www.livescience.com