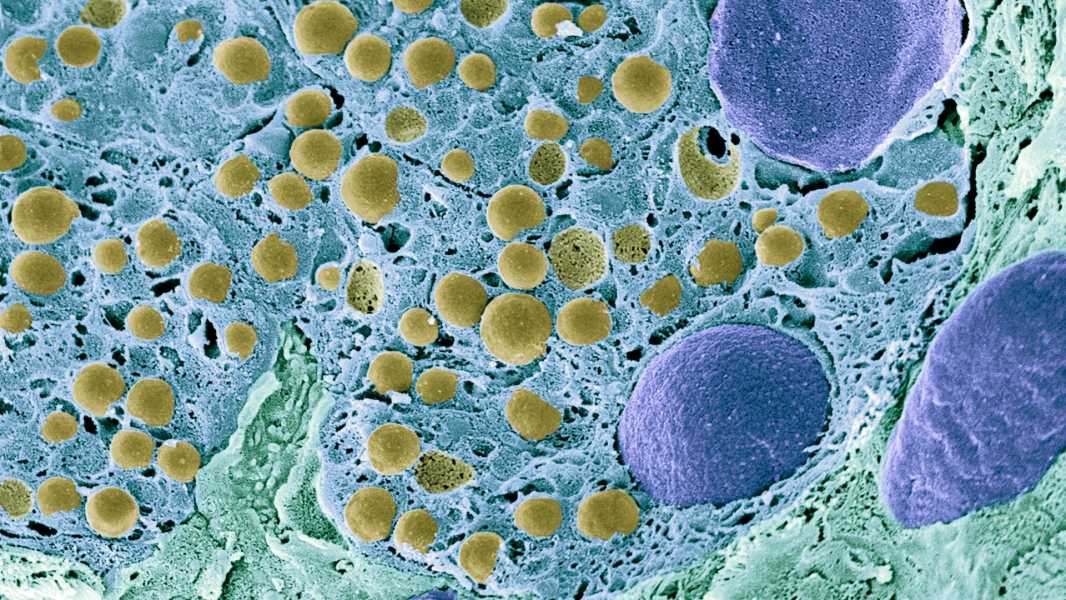

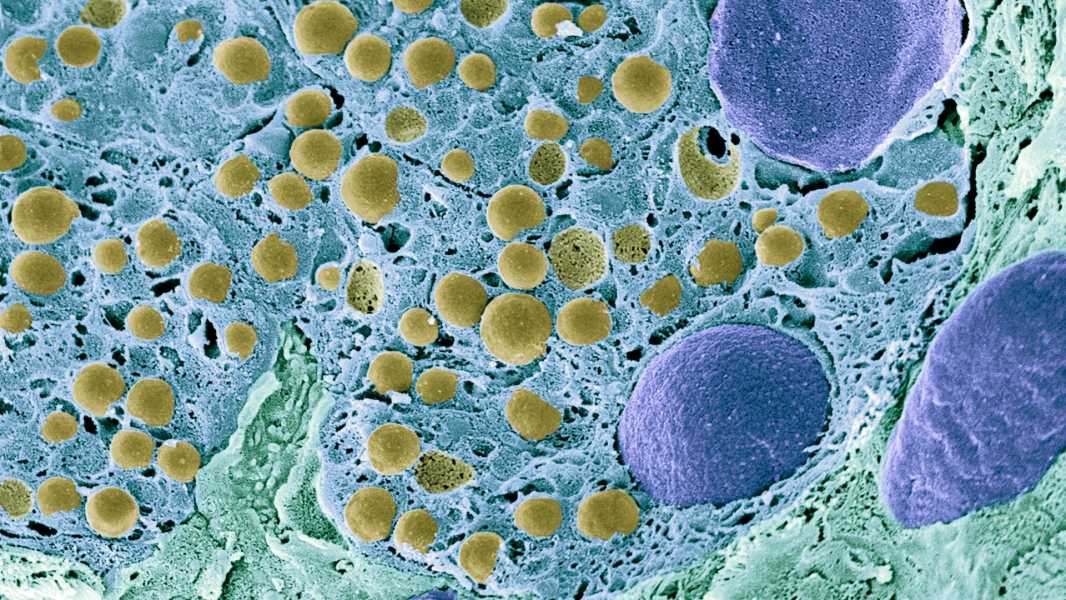

A scanning electron microscope image of pancreatic cells. (Image credit: Science Photo Library – STEVE GSCHMEISSNER via Getty Images)

For the first time, researchers in China have been able to reprogram a woman's fat cells into insulin-producing pancreatic cells, reversing her type 1 diabetes.

The achievement adds to growing evidence that reprogrammed stem cells could one day be used to treat or reverse chronic diseases. A patient treated in a recent study still does not need insulin injections a year after the procedure.

“These results are really 'very interesting,'” said Dr. Kevan Herold, the CNH Long Professor of Immunobiology and Medicine at the Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

Insulin is the chemical key that allows sugar molecules to leave the bloodstream and enter cells, where they can be used as energy. But in type 1 diabetes, the immune system destroys the insulin-producing cells found in large “mini-organs” in the pancreas known as islets.

Without insulin, cells are starved of energy and blood sugar levels rise. In severe cases, this can be fatal because the body begins producing acidic compounds called ketones in an attempt to provide itself with enough energy for cell survival.

In a new study published Thursday (October 31) in the journal Cell, scientists extracted fat cells from a patient with type 1 diabetes and used chemicals to convert them back into “pluripotent” stem cells, which can transform into any cell type.

Once the cells were restored to this state, the scientists chemically induced them to become islet cells. These new islet cells were then implanted into the patient's abdomen.

Before the experimental treatment, the patient struggled to control her blood sugar, spending less than half of her time in the “target” healthy range, lead study author Hongkui Deng, a researcher at the Beijing-Tsinghua Life Science Center at Peking University, told Live Science. After the cell transplant, her time in the target zone “improved to more than 98%,” Deng added in an email to Live Science.

After 75 days of transplantation, the patient no longer needed insulin to maintain her blood sugar levels.

“The speed with which the patient demonstrated reversal of diabetes and achieved insulin independence after transplantation was astounding,” Deng said. “This discovery implies remarkable potential for this therapeutic strategy.”

Transplanting islet cells into patients is not a new technique. For three decades, scientists have been harvesting islets from donor organs and then transplanting the cells into the livers of patients with type 1 diabetes. However, donors are limited in number, and transplant recipients must take powerful drugs for life to suppress their immune systems and prevent rejection of the new mini-organs. As a result, only patients who require other transplants, such as kidney or liver transplants, typically receive donor islet cells.

The patient in this study was no exception. She had previously had a liver transplant and was taking strong immunosuppressant drugs. However, the new type of islet transplant she received represents a step forward: Unlike cells from donor organs, stem cells could provide a potentially unlimited source of new islets.

Cells implanted in the abdomen performed better than those typically transplanted into the liver, demonstrating “markedly improved insulin secretion,” Dan noted. What’s more, the abdomen is easily accessible and can be scanned with MRI, making it easy to monitor the implanted cells for safety and remove them if necessary, he added.

The new study is part of a growing body of evidence that islets derived from stem cells can reverse

Sourse: www.livescience.com