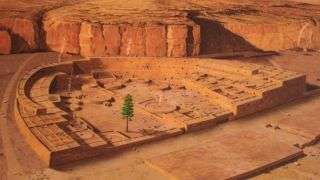

The “Plaza Tree of Pueblo Bonito” was thought to be a living “world tree” for ancestral Puebloans. But researchers have found that it grew 50 miles away and was dead when it was hauled there.

A towering ponderosa pine discovered in the center of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, known as the “Plaza Tree,” was once thought to symbolize life and the center of the world for an ancient pueblo town. But new research suggests it may have been just a giant log no one bothered to move for 800 years, and maybe didn’t hold significant meaning.

“I think the tree was dead when it was transported into the canyon,” said study lead researcher Chris Guiterman, an assistant research scientist who studies ancient trees at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

For over a hundred years, people assumed the tree had meaning; it was regarded as a “tree of life”, according to one researcher, or a “world tree.” The solitary tree was once thought to represent the living “center of the world” for the people of Pueblo Bonito, the largest of Chaco Canyon’s “great houses,” which was occupied between A.D. 850 and 1150. Some speculations placed the tree at the center of a religious cult, and an illustration of a growing “Plaza Tree of Pueblo Bonito” appears in a brochure from the National Park Service.

Guiterman and his colleagues discovered that the Plaza Tree probably didn’t grow at Chaco Canyon, but more than 50 miles (80 kilometers) away. They also found no evidence that the tree had a religious role — it might have been a pole, or a beam for a house, or firewood.

“I actually have no idea whether it did, does, or ever had religious significance,” Guiterman told Live Science in an email. “I don’t know what it was used for, or why it was located in the plaza where it was found.”

“Tree of life”

The researchers studied three aspects of the Plaza Tree: documents about the discovery of its 20 foot (6 meter) long trunk in Pueblo Bonito in 1924; the levels of isotopes of the chemical element strontium within samples of its wood, which can identify where it came from; and the width of its tree rings, which can show seasonal growth.

Ideally, the tree rings would have been compared to rings from trees of the same age, wrote the researchers in the study, published online March 13 in the journal American Antiquity — but that wasn’t possible, so they used the rings in modern trees to determine distinctive growth patterns based on the climate of particular areas.

The researchers found that the tree ring width and the strontium isotopes of the Plaza Tree didn’t match those of ponderosa pine trees that grew around Chaco Canyon — instead, they closely matched trees that grew in the Chuska Mountains, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) west.

The Chuska Mountains region “also happens to be the primary source for architectural wood used to construct Pueblo Bonito and other Chaco great houses,” Guiterman said.

The researchers determined that archaeologist Neil Judd of the Smithsonian Institution, who excavated Pueblo Bonito in the 1920s, failed to find any sign of deep roots from the tree in the plaza where it was found, and initially dismissed the idea that it had been growing there.

But Judd’s dismissal seems to have been overlooked in his following interpretation in the 1950s, when he described the Plaza Tree as the last living remnant of an ancient forest that once existed at Chaco Canyon.

Ancient pueblos

Recent research has shown that logs were often hauled for dozens of miles to build the pueblos at Chaco Canyon, Guiterman said: “hundreds of thousands of timbers were used in construction of [the] great house structures.”

The Plaza Tree is one of only two logs found in an ancestral Puebloan structure that were not parts of buildings. The other is a 32 foot (10 m) long log of white fir at the Kiet Siel cliff dwelling in Arizona, discovered in the 1890s. That unexpected find may have prompted Judd’s more elaborate interpretation of the Plaza Tree, Guiterman said.

“It was a puzzling discovery — one of a kind, really,” he said. “It served as evidence for an early idea that Chaco Canyon was heavily forested before the great houses were constructed, and that the hundreds of thousands of beams came from that local forest.”

The researchers looked again at several theories surrounding the Plaza Tree, including that it served as a gnomon — the upright that casts a shadow — of an ancient sundial. “Although we cannot confirm that [the Plaza Tree] was actually long enough to be a gnomon, it is certainly possible,” they wrote.

The tree may also have served as an upright pole in ceremonies and festivals, such as the pole-climbing that features in some Native American festivals and which may have originated in ancient Mesoamerica, the researchers wrote. The branches and logs of pine trees are used in some Puebloan ceremonies today.

But the Plaza Tree also could have had a much more mundane use. “It might have been a log staged for construction of a new room, or to replace a damaged beam in an existing room,” they wrote. “It could have been a bench, or intended for fuelwood [firewood].”

Sourse: www.livescience.com