Cities like Tehran will be directly affected by the severe subsidence recorded across Iran. (Image credit: BornaMir/Getty Images)

New research shows that the depletion of Iran's underground aquifers is causing rapid land subsidence across the country.

More than 31,400 square kilometers (12,120 square miles) of the country—roughly the size of Maryland—is currently sinking at a rate of more than 10 millimeters (0.39 inches) per year. In a more extreme scenario, land levels have fallen by more than 34 centimeters (1 foot) per year in the Rafsanjan region of central Iran.

You may like

-

'Like a creeping mold spreading across the landscape': A study has found that isolated arid areas around the world are coalescing into 'mega-arid' regions at an alarming rate.

-

Kabul could become the first modern capital to run out of water – and here's why

-

Amazon peatlands have stopped absorbing carbon. What does this mean?

Subsidence measurement

In Iran, approximately 60% of water supply comes from underground aquifers. To study how this affects the surface, Jessica Payne, a doctoral student in the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds (UK), and her colleagues used radar data from the European Space Agency's Sentinel-1 satellite constellation to map land level changes in Iran over eight years, from 2014 to 2022.

The researchers found 106 subsidence areas covering a total of 12,120 square miles, or about 2% of the country's land area.

“Subsidence rates in Iran are among the highest in the world,” Payne told Live Science. “We found about 100 sites across Iran where subsidence is occurring at rates faster than about 10 millimeters [0.4 inches] per year. In Europe, subsidence rates are considered extreme if they exceed 5–8 millimeters [0.2–0.3 inches] per year.”

According to her, the land is subsiding due to groundwater pumping, and 77% of cases of subsidence exceeding 10 mm per year are related to agriculture.

For example, near the city of Rafsanjan, the climate is very dry, there are pistachio plantations, and there is intensive groundwater use. A subsidence of 13 inches (34 cm) per year may not seem like a significant drop, Payne said, “but over 10 years, the ground will sink about 3-4 meters [10-13 feet]; that's really significant.”

In Bardaskan in northern Iran, the area affected by subsidence was 429 square miles (1,110 square kilometers), 40 percent larger than the area recorded in the 2008 study. The work by Payne and her colleagues was published August 27 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.

“Irreversible” flooding

Much of the subsidence in all 106 locations was irreversible, Payne said.

You may like

-

'Like a creeping mold spreading across the landscape': A study has found that isolated arid areas around the world are coalescing into 'mega-arid' regions at an alarming rate.

-

Kabul could become the first modern capital to run out of water – and here's why

-

Amazon peatlands have stopped absorbing carbon. What does this mean?

“The most striking finding of the paper is that most of the groundwater subsidence in Iran is irreversible, highlighting the severity of aquifer depletion,” Shirzai said.

She noted that aquifers don't act like reservoirs. When more water is extracted from a reservoir than is entering it, the water level drops. But when it rains, it can refill.

According to Payne, aquifers where roughly equal amounts of water are withdrawn and replenished by precipitation each year exhibit a seasonal trend called elastic recharge. But when significantly more water is withdrawn, the situation changes.

“Inside an aquifer, it's like a bucket of sand. There are layers of mud and layers of sand, and the water holds these mud and sand particles together,” Payne explained. “But if that water is removed, and it hasn't been removed before, the sand and mud won't be strong enough to hold all those sediments on top, or the buildings on top.”

Iran is facing an ongoing drought that is worsening soil subsidence.

As a result, the particles become compressed, and the ground level drops, causing irreversible subsidence. Even if water returns to the system and penetrates the compacted areas, it won't raise the ground level to its previous level, she said.

The consequences are serious. “Steep slopes create cracks and lead to structural instability, damaging buildings, roads, and railways,” Shirzai said. “Cities like Tehran, Karaj, Mashhad, Isfahan, and Shiraz are directly affected. In Karaj alone, more than 23,000 people live in high-risk zones.”

“It's hard to hear about the impact outside of Iran, but some reports from Iranian counterparts say the buildings have had to be abandoned,” Payne said.

Soil subsidence is not unique to Iran.

“Unfortunately, the scenario envisioned for Iran echoes the scenario seen in many other countries and their megacities,” Francesca Cigna, a researcher at the Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate in Rome, Italy, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

Other places seeing big drops, she said, are major cities in central Mexico, the United States, China and Italy.

—Ancient groundwater records offer a worrying forecast for the US Southwest.

The Colorado River Basin's groundwater won't run out, but we'll eventually be unable to access it, scientists warn.

—Drinking water, building an island from scratch, and creating an urban forest: three bold ways cities are already adapting to climate change.

“Iran's peak subsidence levels are comparable to Mexico City and California's Central Valley, making it one of the most extreme subsidence hotspots in the world,” Shirzai said.

Disasters associated with ground subsidence are not uncommon. For example, in Mexico, ground subsidence is believed to have caused a subway line collapse in 2021, killing 26 people and injuring dozens.

Another major risk is the loss of freshwater reserves. “Continued compaction of the aquifer means that a significant portion of its storage capacity will be irreversibly lost,” Shirzai said. “This exacerbates water shortages during droughts, reduces resilience to climate change, and makes recovery increasingly impossible.”

Chris Simms, Live Science contributor

Chris Simms is a freelance journalist who previously worked at New Scientist magazine for over 10 years, serving as editor-in-chief and assistant news editor. He was also a senior editor at Nature and holds a degree in zoology from Queen Mary, University of London. In recent years, he has written numerous articles for New Scientist and was shortlisted for the 2018 British Science Writers' Association Best Newcomer award.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

'Like a creeping mold spreading across the landscape': A study has found that isolated arid areas around the world are coalescing into 'mega-arid' regions at an alarming rate.

Kabul could become the first modern capital to run out of water – and here's why

Amazon peatlands have stopped absorbing carbon. What does this mean?

New research shows that dams around the world are holding back so much water that they are shifting the Earth's poles.

Glaciers in North America and Europe have lost “unprecedented” amounts of ice over the past four years.

Why were the Texas floods so catastrophic?

Latest news on planet Earth

Hurricane Fujiwara's rare 'dance' could spare the East Coast from the worst of Tropical Storm Imelda.

Trees in the Amazon rainforest are resisting climate change by growing thicker due to CO2 in the atmosphere.

Strange glass in Australia appears to be formed by a giant asteroid impact, but scientists 'have yet to find the crater'

Unusual diamonds from South African mine contain 'almost impossible' chemicals

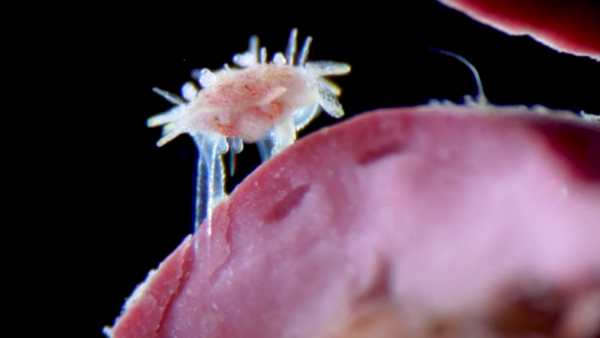

A microscopic baby sea urchin crawling on tube feet has been named one of the winners of Nikon's Small World in Motion video competition.

Scientists have discovered 85 “active” lakes buried beneath Antarctic ice.

Latest news

The ancient Egyptian statue of “Messi,” found in the Saqqara necropolis, is “the only known example of its kind from the Old Kingdom.”

The study found that Iran is among the “world's most subsiding hotspots,” with some areas sinking by up to 30 cm per year.

A 30,000-year-old “personal toolkit” discovered in the Czech Republic offers a “very rare” glimpse into the life of a Stone Age hunter-gatherer.

Is acetaminophen safe during pregnancy? Here's what the science says.

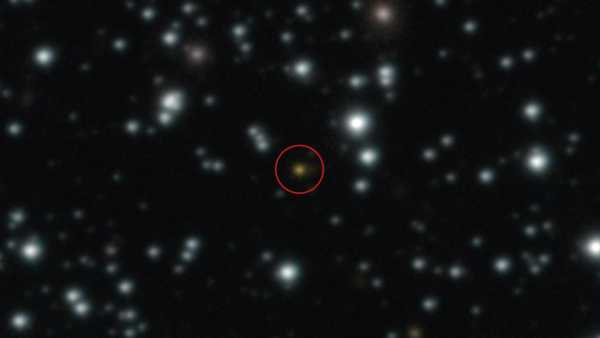

Scientists say the mysterious cosmic explosion cannot be explained.

Physicists have found a loophole in Heisenberg's uncertainty principle without violating it

LATEST ARTICLES

1The ancient Egyptian statue of “Messi”, found in the necropolis of Saqqara, is “the only known example of its kind from the Old Kingdom.”

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com