An artist’s depiction of a star brushing past a black hole.

This black hole’s parents never told it not to play with its food.

An astronomer thinks he’s spotted a stellar corpse known as a white dwarf sending out blazes of light, mayday signals from its uncomfortably close orbit of a black hole. And while such a white dwarf is usually the result of a star naturally running out of fuel and exploding, the scientist thinks the black hole itself snatched all of a red giant’s free gas away, triggering the premature death. Such is the peril of treading too close to a black hole even if it can’t gobble you up.

“In my interpretation of the X-ray data, the white dwarf survived, but it did not escape,” Andrew King, author of the new research and an astrophysicist at the University of Leicester in the U.K., said in a NASA statement. “It is now caught in an elliptical orbit around the black hole, making one trip around about once every nine hours.”

Video: Star captured by black hole’s gravity, blasts x-rays

Related: No escape: Dive into a black hole (infographic)

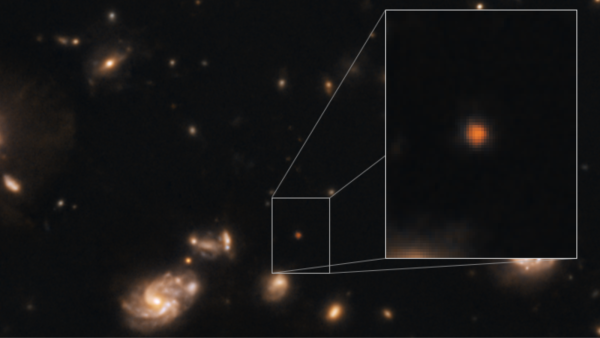

King’s new research is based on observations gathered by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton X-ray telescope. The pair focused on drama unfolding in a galaxy called GSN 069, located about 250 million light-years away from Earth.

Every nine hours or so, the galaxy experiences a spike in X-ray emissions. By analyzing those spikes, King came up with his theory of a so-called near-miss tidal disruption event. (Scientists have studied plenty of tidal disruption events, in which a black hole tears apart a star that comes too close.)

When a red giant first snuck too close, the black hole snatched away all its hydrogen, leaving just the core white dwarf behind. But the black hole, which contains about 400,000 times the mass of the sun — a bit puny for a supermassive black hole — couldn’t finish the job. Instead, it trapped the white dwarf in a nine-hour dramatically elongated orbit, and at the closest point of each loop, the black hole again sucks up a bit more of the star’s matter, munching away at its meal.

“It will try hard to get away, but there is no escape. The black hole will eat it more and more slowly, but never stop,” King said. Right now, he calculated, the star is about one-fifth the mass of our sun. But in about a trillion years, if the dynamic continues, it could end up as a planet with about the same mass as Jupiter, he added. “This would be a remarkably slow and convoluted way for the universe to make a planet!”

So far, these observations are quite uncommon, but the fact that scientists caught the interplay at all suggests such near-misses may not stay that way.

“In astronomical terms, this event is only visible to our current telescopes for a short time — about 2,000 years,” King said. “So unless we were extraordinarily lucky to have caught this one, there may be many more that we are missing.”

The research is described in a paper published Feb. 7 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Sourse: www.livescience.com