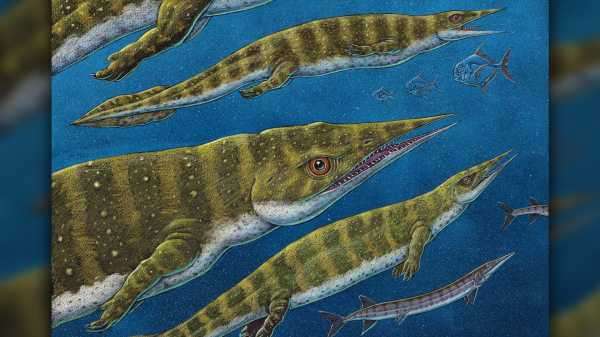

Artist’s depiction of Gunakadeit joseeae.

Scientists just discovered the remains of a weirdo sea creature with a “tweezer snout” that would have roamed the seas hundreds of millions of years ago.

Known as thalattosaurs (“ocean lizard”), these reptiles measured up to 16 feet (5 meters) in length, and were around for about 40 million years during the latter part of the Triassic period (251 million to 199 million years ago). They are known from a scant collection of fossils, but the find in Alaska provided researchers with the most complete thalattosaur skeleton unearthed in North America.

. “The water was lapping at the edge of the site.”

From left, Gene Primaky, Jim Baichtal and Patrick Druckenmiller stand in rising waters after the thalattosaur fossil was removed. Minutes later, the tide submerged the excavation site.

They identified the find as a thalattosaur that would have measured 30 to 35 inches (75 to 90 centimeters) long when it was alive. Its scientific name — Gunakadeit joseeae (guh-nuh-kuh-DATE JOE-zee-ay) comes from the name of a sea monster of the Tlingit culture, and the name of Primaky’s mother, Joseé Michelle DeWaelheyns, according to the study.

Not only was it a newfound species and the most complete thalattosaur skeleton found in North America, “it was also potentially the youngest occurrence of the group that we know of,” Druckenmiller told Live Science.

“In other words, it’s one of the last kind of thalattosaurs alive before they went extinct,” he said.

Poking for prey

Thalattosaurs, of which there are around 20 known species (mostly from Europe and China) have varying shapes of jaws and teeth, possibly because they targeted different prey.

“Some of these animals have no teeth; some of them have blunt, shell-crushing teeth; some of them have pointy teeth,” Druckenmiller told Live Science.

G. joseeae had teeth in the back of its jaw but was lacking teeth in the pointed front part. “So it looks like they were using a wholly different feeding strategy that we’ve never seen before in this group — or in any reptiles, really,” he added.

The fossil of Gunakadeit joseeae, which was found in southeastern Alaska. About two-thirds of the tail had eroded away when the fossil was discovered.

Clues preserved in the rocks around the fossil suggested that the animal lived in a tropical coastal ecosystem that was home to coral reef habitats; its pointy snout would have been well-suited for combing the shallows and poking into cracks and crevices to dislodge small fish and crustaceans. Once G. joseeae nabbed its prey, it would clamp down with its back teeth “and then suck it in,” Druckenmiller said.

Having highly specialized feeding methods likely helped thalattosaurs to thrive, but may have also doomed them when ocean conditions changed and disrupted their habitats, the scientists wrote in the study. By comparison, marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs survived the mass extinction that ended the Triassic, and they may have done so because their feeding behavior wasn’t as finely tuned as that of the needle-nosed thalattosaurs.

“Their environment changed so radically at the end of the Triassic that they simply couldn’t survive, and the group went extinct,” Druckenmiller said. “What might have happened is that thalattosaurs got a little too specialized for their own good.”

The findings were published online Feb. 4 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Sourse: www.livescience.com