Male cicadas infected by a particularly gruesome parasitic fungus become zombies with an undercover mission: They broadcast a female’s sexy come-hither message to other male cicadas, luring their unsuspecting victims to join the zombie cicada horde.

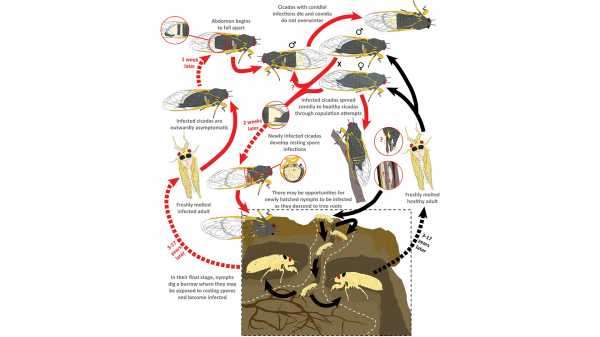

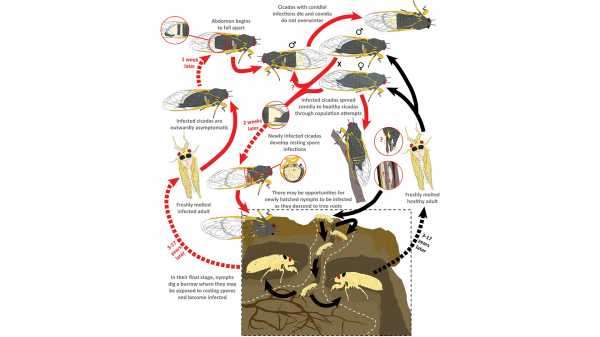

Researchers recently discovered this unusual twist to the cicada’s already horrific zombification story. As the parasitic fungus called Massospora eats away at a cicada’s abdomen, replacing it with a mass of yellow spores, the fungus also compels males to flick their wings in movements that are typically performed by females to attract mates.

Healthy males that hurry over for female company, then try to mate with the infected male, which passes along the Massospora infection. This and other new discoveries are helping scientists to piece together how Massospora turns cicadas into mind-controlled zombies, according to a new study published online June 18 in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

This zombie-host relationship can be challenging to observe. Though the fungus can affect cicadas that emerge annually, many of its cicada hosts are in the Magicicada genus, also known as periodical cicadas. These black-bodied and red-eyed cicadas spend 13 to 17 years (depending on the species) underground as immature nymphs. Luckily for the scientists who study periodical cicadas, local populations known as broods that follow this cycle emerge during different years in different locations.

“It would be very difficult to maintain a research program and train scientists if new samples only arrived every 13 to 17 years,” said lead study author Brian Lovett, a researcher with the Division of Plant and Soil Sciences at West Virginia University (WVU).

“Road trips to collect from and observe broods are very common among cicada researchers,” Lovett told Live Science in an email. “Aside from ‘following the brood,’ ‘sharing the brood’ [providing colleagues with access to collected specimens] is also standard practice.”

Once the cicadas emerge and molt their exoskeletons, they enjoy just a few weeks of life on the surface as adults, mating and laying eggs before dying.

Fungal spores may infect the cicadas as nymphs or as adults.

However, for cicadas infected by Massospora, life takes an ugly turn. About a week after being infected, fungal spores devour the cicada’s abdomen and its body disintegrates — but the insect doesn’t die. Rather, it continues to fly around and disperse the zombifying spores far and wide in a process known as active host transmission (AHT), in which a parasite manipulates its living host.

As Lovett and his colleagues reported, one form of that manipulation compels infected males to imitate female behaviors, moving their wings to lure and infect even more cicadas.

“To our knowledge, this is the only example of AHT in which the pathogen behaves at least in part as a sexually transmitted disease,” as transmission sometimes happens when males attempt to copulate with other males, the researchers wrote in the study.

Related Content

– 6 amazing facts about cicadas

– The 10 most diabolical and disgusting parasites

– No creepy crawlies here: Gallery of the cutest bugs

At least some of the chemical cues responsible for the cicadas’ unnatural behavior are psychoactive; one of these is psilocybin, which is also found in hallucinogenic mushrooms, Live Science reported in 2019. But though scientists have identified some of the chemicals in Massospora fungus, the spores’ mechanisms for controlling its cicada host have yet to be explained, according to the study.

“These discoveries are not only super cool but also have a lot of potential in helping us understand insects better, and perhaps learn better ways to control pest species using fungi that manipulate host behaviors,” study co-author Angie Macias, a WVU doctoral candidate, said in a statement.

“It is almost certain that there are undiscovered Massospora species, never mind the other AHT (active host transmission) fungi, and each of these will have developed its own intimate connection with its host’s biology,” Macias said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sourse: www.livescience.com