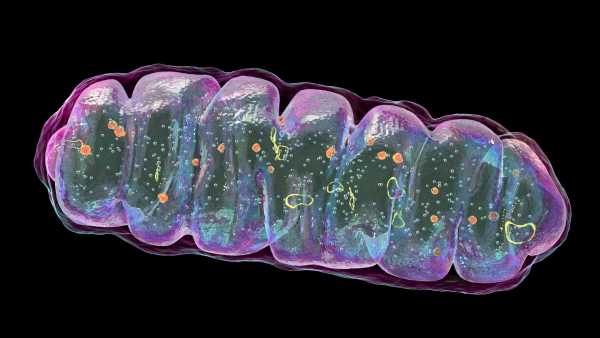

Using a new enzymatic technology, researchers transplanted a kidney with blood type A into a recipient with blood type O. (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

In a step toward expanding access to donor organs, scientists converted a kidney with blood type A into a kidney with blood type O and then transplanted it into a brain-dead person.

The kidney, which has effectively become a universal organ for transplantation, functioned normally for two days before showing signs of rejection. If improved, this strategy could reduce waiting times on organ donor lists.

You may like

-

Scientists created human eggs from skin cells and then used them to create embryos.

-

Doctors restored a man's vision by removing a tooth and implanting it in his eye.

-

In the first study, congenital deafness in adolescents and adults was treated with a new gene therapy.

Kidney transplantation has been a treatment option for patients with renal failure since the 1950s. However, like any organ transplant, it has some limitations, including the need to match the donor's and recipient's blood types, as well as the need to find an organ of suitable size located close enough to the transplant site.

Humans have four main blood types—A, B, AB, and O—and the immune system of a person with one blood type can react to another. For example, a transplant candidate with blood type O can only receive a kidney with type O, but a person with A, B, or AB can also receive a kidney with type O. This is because each blood type is determined by immune-stimulating substances called antigens. O blood lacks these antigens, so it can be transfused to anyone, while other blood types activate the immune system of a person with type O.

However, in the late 1980s, scientists developed a method for transplanting ABO-incompatible (ABOi) organs—organs from a donor with one blood type to a donor with an incompatible blood type—to recipients in need. However, this process is labor-intensive and takes several days. Then, in 2022, researchers developed an enzyme-based treatment protocol that converts an organ into a “universal” transplant, called enzyme-converted O2 (ECO).

“The effectiveness of the IVF process has been demonstrated in the lungs,” study co-author Stephen Withers, a professor emeritus of biochemistry at the University of British Columbia, told Live Science in an email. “We hope it will work for other organs as well—as it should!” (Earlier this year, another research team reported transforming a kidney using IVF, but they began their experiment with kidneys from people with blood type O.)

Withers was part of the 2022 team that transplanted lungs from type A to type O. However, in that pilot study, the team did not transplant lungs obtained through IVF into humans. In the new study, Withers and his colleagues used a kidney from type A, deemed unsuitable for transplant, and transplanted it into type O, perfusing the kidney with a special fluid. This process took about two hours.

“Perfusion devices and organ preservation solutions are often used to maintain organs in good condition between donation and transplantation,” Withers explained. To transform the organ, researchers add specialized enzymes to the perfusion fluid that remove blood type antigens that can cause rejection.

“This way, the organs won't be recognized and attacked by anti-A antibodies present in the recipient's bloodstream,” Withers said. The procedure doesn't permanently rid the organ of problematic antigens, but it can help prevent the most severe immune system response.

You may like

-

Scientists created human eggs from skin cells and then used them to create embryos.

-

Doctors restored a man's vision by removing a tooth and implanting it in his eye.

-

In the first study, congenital deafness in adolescents and adults was treated with a new gene therapy.

To test whether a kidney could avoid immediate rejection in humans, the team approached a brain-dead recipient whose family had consented to the study. The team transplanted a kidney obtained through IVF into a recipient with high levels of antibodies to the A-antigen.

In a typical transplant, the recipient is given antibody therapy before and after the transplant to prevent “hyperacute” rejection, which develops quickly. However, the research team wanted to test whether creating an IVF kidney would prevent early rejection, so they did not use this therapy.

“We needed to understand how the processes unfold,” Withers said. They wanted to track the rate of antigen reappearance in the kidney and how long the recipient's body could tolerate this reappearance.

Researchers found that the IVF-transplanted kidney functioned well for two days after transplantation, with no signs of rejection. An immune response to the new kidney emerged on the third day, when the IVF-transplanted kidney began producing new A antigens.

“In real-world clinical transplantation, there are a number of procedures that can be used to minimize primary antibody-mediated rejection, including optimized immunosuppression,” Withers said. If these methods, which are standard treatment for any organ transplant, are also applied to kidney transplantation after IVF, this could lead to longer-lasting graft tolerance.

RELATED STORIES

— The first ever attempt to transplant lungs from a pig to a human in China was made in a brain-dead person.

A diabetic man produces his own insulin after receiving a genetically modified cell transplant.

A “universal” cancer vaccine being prepared for human trials could be useful for “all forms of cancer.”

The researchers note in their study that converting organs from one blood type to another is important for expanding patient access to donor organs. This is especially important for “transplant candidates with blood type O, who make up more than 50% of the waiting list and typically wait 2–4 years longer for a transplant than patients with other blood types,” they note.

Although the IVF kidney was successfully transplanted, the development of this transplant process is still in its early stages.

“I don't know if it will be used everywhere,” Withers said. “But it's certainly a possibility.”

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not contain medical advice.

Christina Killgrove, Social Link Navigation, Staff Writer

Christina Killgrove is a staff writer for Live Science, specializing in archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in publications such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Christina holds a PhD in biological anthropology and an MA in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a BA in Latin from the University of Virginia. She previously worked as a university professor and researcher. She has received awards for her research from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

Scientists created human eggs from skin cells and then used them to create embryos.

Doctors restored a man's vision by removing a tooth and implanting it in his eye.

In the first study, congenital deafness in adolescents and adults was treated with a new gene therapy.

This week's science news: the world's first pig-to-human lung transplant and the successful test flight of the SpaceX Starship.

8-year-old child with rare fatal disease shows significant improvement after experimental treatment

8 children saved from potentially fatal inherited diseases thanks to new IVF research using 'mitochondrial donation'

Latest news in the healthcare sector

HPV vaccination reduces the incidence of cervical cancer in both vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

Wildfire smoke-related deaths in the US could reach 70,000 a year by 2050 due to climate change, according to a study.

Scientists created human eggs from skin cells and then used them to create embryos.

Years of repeated blows to the head increase the risk of CTE—even if they aren't concussions.

Heart Quiz: What Do You Know About the Body's Hardest-Working Muscle?

A woman developed unusual bruises from a massage gun. It turned out she had scurvy.

Latest news

Scientists transplant a kidney from blood type A to the universal blood type O and implant it into a brain-dead recipient.

Divers have recovered more than 1,000 gold and silver coins from the Treasure Fleet, a ship that sank in Florida in 1715.

Chimpanzees eat fruits full of alcohol, but no, they don't get drunk.

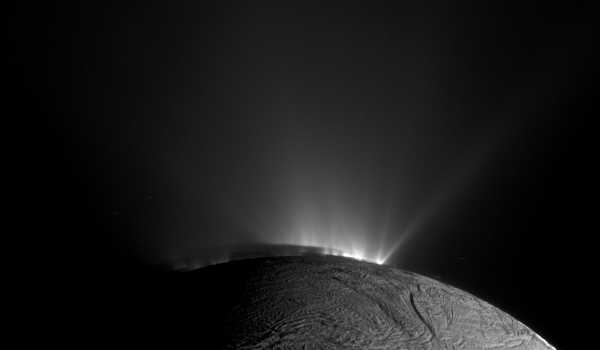

Scientists have found irrefutable evidence that the icy moon Enceladus is habitable.

Jane Goodall, the renowned primatologist who discovered chimpanzee tool use, has died at age 91.

New research has shown that the Bering Land Bridge formed much later than we thought.

LATEST ARTICLES

1History of Science: Invention of the Transistor Opens the Era of Computing – October 3, 1950

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com