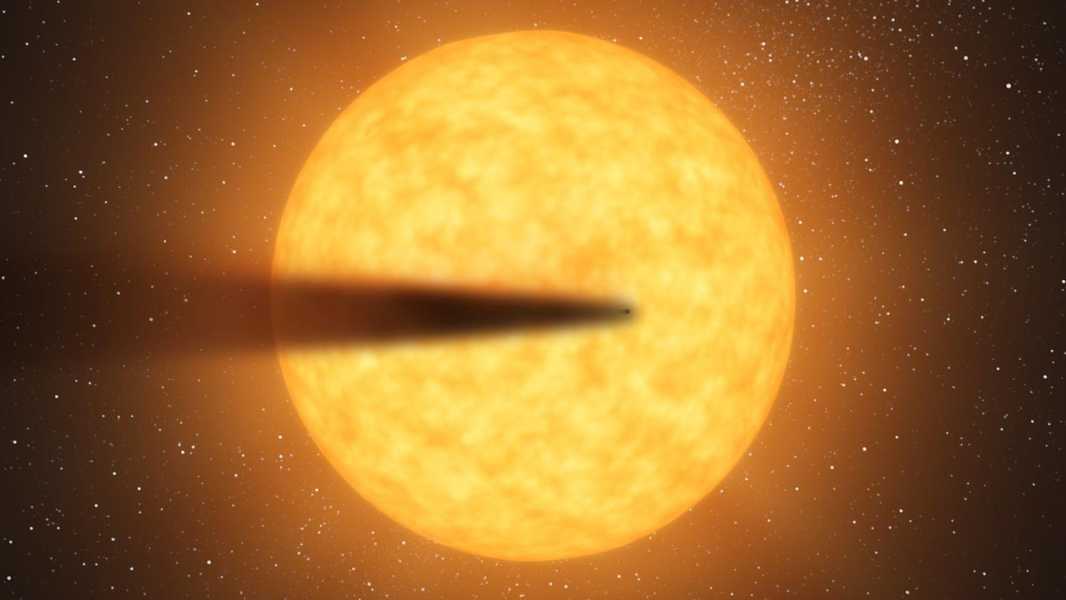

An artist's concept depicts the comet-like tail of a potential disintegrating planet passing in front of its parent star. (Image credit: NASA)

Astronomers have directly observed for the first time two worlds outside our solar system shedding their outer layers into space. The new data provides an unprecedented look at the planets' interior structures—an insight long elusive, even on Earth.

The first exoplanet to “break apart” is a rocky world comparable to Neptune known as K2-22b, which orbits its star so closely that it completes a full orbit every nine hours. Scientists say the star’s heat is actually frying the planet: K2-22b’s surface is hotter than 3,320 degrees Fahrenheit (1,826 degrees Celsius), hot enough to not only melt rock but also vaporize it. Recent observations of K2-22b using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have shown that the vaporized rock has formed an elongated, comet-like tail.

“This is an exciting and exciting opportunity to understand the interior structure of the terrestrial planets,” study co-author Jason Wright, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State University, said in a statement.

But it’s not the only evaporating planet discovered recently. Another disintegrating exoplanet orbiting another star was discovered by a separate team using the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). This hot world, called BD+054868Ab, is the closest evaporating exoplanet to Earth found to date.

TESS data show that BD+054868Ab has not one but two massive tails: a main tail made up of larger particles the size of a grain of sand, and a second tail made up of smaller particles the size of soot. Together, the tails span a whopping 5.6 million miles (9 million kilometers), taking up about half the planet's orbit.

“These planets are essentially throwing their guts out into space for us to study,” said Nick Tusey, a graduate student in the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State who led the JWST study. “With JWST, we finally have the ability to analyze their composition and understand what planets around other stars are actually made of.”

The papers detailing the findings on both exoplanets were uploaded as preprints and are still undergoing peer review.

“Who ordered this?”

The results came after TESS and JWST observed thousands of stars, looking for subtle but periodic dips in light that occur when a planet passes in front of its star. These dips, known as transits, reveal spectral fingerprints of planets’ chemical compositions, allowing astronomers to reverse engineer what the interiors of collapsing planets might once have looked like.

For example, while studying K2-22b, JWST detected gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide. This is unusual because these gases are usually associated with icy bodies, not the mantles of terrestrial planets, and they should have evaporated into space long ago.

“It was really a 'Who ordered this?' moment,” Tusey said in a statement.

Tusay and his colleagues suggest that K2-22b may have originally formed far from its star and been moved closer to it by gravitational perturbations, which should not be uncommon given that the star it orbits shares its cosmic region with another star.

Meanwhile, BD+054868Ab is likely losing about a moon's worth of material every million years. By current estimates, astronomers predict it will cease to exist in about 1 to 2 million years — a blink of an eye compared to the typical lifespan of planets in less extreme environments, which last billions of years.

Sourse: www.livescience.com