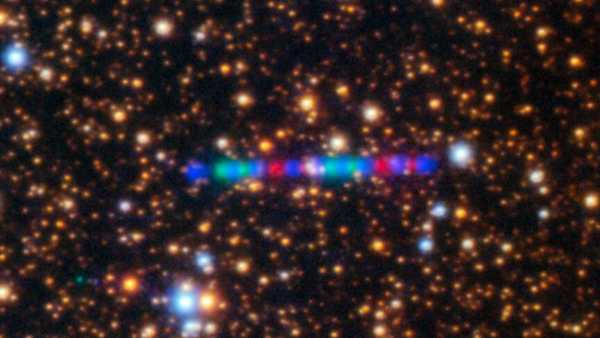

The annotated area in this animation of the Red Planet is where NASA spacecraft have found near-surface water ice that would be easy for astronauts to dig up.

The 2010s saw big advances in Mars exploration, but the new decade may bring even more exciting news — the possible discovery of Red Planet life.

Scientists learned a great deal about the history and evolution of Mars in the last 10 years. NASA’s Curiosity rover mission led the charge, determining that at least some parts of the planet were capable of supporting Earth-like life for long stretches in the ancient past.

“It’s been a very successful and very enlightening mission, in terms of figuring out that Mars was a habitable planet,” Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said last month during a media roundtable at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco. “And now we can go [to] the next step of the program and figure out if life ever took hold.”

That next step begins this July with the launches of NASA’s 2020 Mars rover and the European-Russian rover Rosalind Franklin, both of which will hunt for signs of ancient Red Planet organisms.

But the alien-life hunt may not be the only Mars-exploration front opening in earnest in the 2020s. If the development of SpaceX’s Starship Mars-colonizing vehicle goes well, it’s possible that humanity could put boots on the Red Planet in the next 10 years as well.

A new phase

NASA has hunted for Mars life before. The agency’s Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers, which in 1976 became the first spacecraft ever to touch down on the Red Planet, each carried four biological experiments. But the Vikings returned ambiguous results, forcing a strategy rethink.

The Viking missions “showed us that life is pretty difficult to find,” Vasavada said.

NASA scientists and officials came to grips with this fact, and with the realization that it wasn’t even clear if the conditions necessary for life as we know it had ever prevailed on Mars, he added. So, the agency embarked on a strategic exploration program designed to characterize the Red Planet in detail with a series of orbiter, lander and rover missions.

This work reached a crescendo in the 2010s. Curiosity and the smaller rovers Spirit and Opportunity plied their trade in the last decade, as did the InSight lander and its two fly-along cubesats and the orbiters Mars Odyssey, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution, or MAVEN. (Spirit barely makes this list; the golf-cart-size rover last communicated with Earth in March 2010.)

And NASA didn’t monopolize Mars exploration in the 2010s. India launched its first Red Planet craft, the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), in 2013. Also eyeing the planet from aloft during the decade were Europe’s long-lived Mars Express orbiter and the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), whose March 2016 launch took the European-Russian ExoMars program into space. (Rosalind Franklin and its accompanying landing platform, Kazachok, represent the second phase of the two-part ExoMars.)

The past tense is not really appropriate for many of the above craft, by the way: Curiosity, InSight, Mars Odyssey, MRO, MAVEN, MOM, Mars Express and TGO all remain active today.

The work done by these robots and their predecessors has paved the way for Mars 2020 and Rosalind Franklin. For example, Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity and the orbiters spotted lots of evidence of past water activity on the Red Planet’s surface. Curiosity dug even deeper, identifying an ancient lake-and-stream system inside Mars’ 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater. And MAVEN provided valuable temporal context, finding that the Red Planet likely had lost most of its atmosphere — which had kept Mars warm enough to support liquid surface water — to space by about 3.7 billion years ago.

“I think the evidence is compelling that Mars has met, in the past, all the requirements for either the occurrence of life or an origin of life, depending on how you think something might have played out,” MAVEN principal investigator Bruce Jakosky, of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, told Space.com at the AGU meeting last month.

Two life-hunting rovers

That brings us to Mars 2020 and Rosalind Franklin. The ExoMars rover is scheduled to touch down in March 2021, likely in Oxia Planum, a plain in the Red Planet’s northern hemisphere that shows lots of evidence of ancient water activity.

The solar-powered Rosalind Franklin will use its cameras and scientific instruments to search for morphological and chemical signs of ancient Mars life. The rover will be able to dig deep for such clues; it’s equipped with a drill that can bore 6.5 feet (2 meters) below the Red Planet’s surface.

Mars 2020, which will soon get a more memorable moniker via a student naming competition, will do similar astrobiology work inside the 28-mile-wide (45 km) Jezero Crater. (The rover will gather a variety of other data — and test out new exploration tech, including a tiny Mars helicopter — as well.)

Scientists think Jezero was home to a lake and a river delta in the ancient past, so it’s a good hunting ground on multiple fronts for the NASA rover. Not only was that ancient environment potentially habitable, but river deltas here on Earth are good at preserving biosignatures, mission team members have said.

“We are very much hoping that, with our payload, we can make a very strong case that there are biosignatures on the surface of Mars,” Mars 2020 deputy project scientist Katie Stack Morgan of JPL said at the AGU media roundtable last month.

Mars 2020 won’t be able to drill nearly as deep as Rosalind Franklin. But the NASA rover will do some specialty boring of its own, collecting and caching several dozen samples for eventual return to Earth, where they can be scrutinized in detail by teams of scientists in well-equipped labs around the world.

This is a key aspect of the 2020 rover mission. After all, confirming the existence of ancient biosignatures on Mars, if any are indeed there to be found, is likely to be a tricky business, said Jim Bell of Arizona State University, principal investigator of Mars 2020’s Mastcam-Z instrument.

“We could make a claim about a biosignature, but it’s not clear anyone would believe us,” Bell said at the AGU roundtable. “So, let’s bring the samples back.”

Getting the Mars material here will be a joint effort between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). Europe recently affirmed its financial commitment to the complicated sample-return effort, but NASA is still waiting for its official budgetary go-ahead.

If that green light does indeed come, the 2020s will likely get another serious jolt of spaceflight electricity. The current, still-unconfirmed plan envisions launching a NASA mission called Sample Retrieval Lander (SRL) in 2026. SRL will include a stationary lander, the ESA-provided Sample Fetch Rover and a rocket called the Mars Ascent Vehicle, which will blast the material collected by Mars 2020 into space. These precious samples would make it to Earth in 2031.

Boots on the red ground?

There will be much more Mars activity in the 2020s as well — a lot just this year, in fact, if all goes according to plan.

China aims to launch an orbiter-rover mission to the Red Planet this summer, in the same July-August window that Mars 2020 and Rosalind Franklin are targeting. (Such windows come just once every 26 months, when Earth and Mars align properly for interplanetary missions.)

These would be the first Chinese probes to make it to Mars, but not the first to try. An orbiter called Yinghuo-1 launched in November 2011 aboard Russia’s Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, which never made it out of Earth orbit.

The United Arab Emirates also plans to notch its first Red Planet success soon: the nation aims to launch an orbiter called the Hope Mars Mission this summer. Japan — whose only Mars mission to date, the Nozomi orbiter, failed in 1998 — is working to send a lander toward the Red Planet in 2022 and a sample-return mission to the Mars moon Phobos in 2024. India’s MOM 2, which may include a lander and/or rover along with an orbiter, could lift off in that same general timeframe.

And then there’s the realm of human spaceflight. NASA is working to put boots on Mars sometime in the 2030s, with plenty of help from its international partners and the private sector. But SpaceX has a more ambitious timeline.

Elon Musk’s company is developing a giant, reusable rocket-spaceship combo known as Starship to make colonization of the Red Planet economically feasible. Starship could end up helping set up a million-person city on Mars within the next 50 to 100 years if all goes well, Musk has said.

And Starship’s first interplanetary forays should come much sooner than that. SpaceX aims to launch an uncrewed Starship mission to the lunar surface as early as 2022, company president and chief operating officer Gwynne Shotwell recently said. That flight might be a contracted NASA mission; the agency recently announced that SpaceX is eligible to deliver robotic NASA payloads to the moon’s surface using Starship.

Crew-carrying milestones could follow in relatively short order. For example, Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa has booked a round-the-moon mission aboard Starship, with a target launch date of 2023.

Such timelines may prove to be overly ambitious. After all, the only Starship version that’s gotten off the ground to date is a stubby, single-engine prototype called Starhopper, and the first full-size variant of the spaceship blew its top during its initial pressure test this past November. But SpaceX has a track record of achieving impressive spaceflight feats, as its dozens of rocket landings and many cargo missions to the International Space Station attest.

So stay tuned. With or without a crewed Mars mission, the next 10 years should be a wild Red Planet ride!

Sourse: www.livescience.com