Ancient microbial mounds called stromatolites could be a model for how coastal cities survive rising seas in this era of rapid climate change, according to experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats.

Keeping coastal cities alive in the future may require looking back — very far back.

Thanks to anthropogenic climate change, sea level is rising at an alarming clip, threatening to swamp iconic metropolises like New York, Mumbai and Shanghai in the not-too-distant future. But residents of these and other vulnerable areas don’t necessarily have to flee the coming flood, according to experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats.

Coastal dwellers could shelter in place, Keats believes, if they drew inspiration from the first “cities” that Earth ever supported: layered mounds called stromatolites, the oldest of which date back 3.5 billion years.

Stromatolites record the daily strivings of millions of microbes, many of them photosynthetic cyanobacteria. The mounds grow as these little creatures move upward and outward to catch the sun’s life-giving rays, each sticky “biofilm” layer trapping sediment that firms up the structure.

This action generally takes place in shallow water, especially tidal environments such as the shores of Western Australia’s Shark Bay, one of the few places where stromatolites still flourish. (Stromatolites are much more common in the fossil record.)

Artist and experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats.

This habitat will start to invade many big cities around the world before long, if climate change continues on its present course (which seems likely, given humanity’s inaction thus far, scientists say). And stromatolites display adaptability and an admirable community spirit: As the mound grows, layers that had harbored active sunseekers get subsumed into the interior, shifting into a structural-support role.

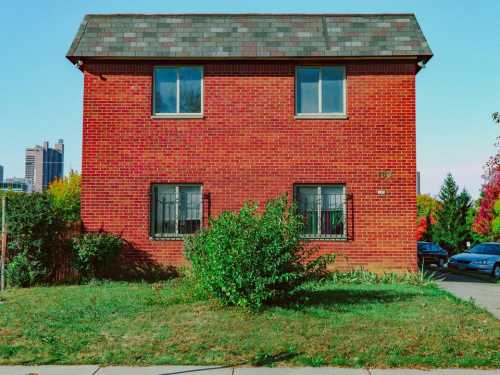

So, Keats believes stromatolites have a lot to offer modern city planners. And he’s aiming to get that point across with his new Primordial Cities Initiative, an interdisciplinary art project that draws in the expertise of researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics (IBP) in Germany.

Over the past year, Keats and his colleagues have devised new skyscraper designs that allow inhabitants to build upward, layer by layer, to stay above the rising waters. They’ve also drawn up a preliminary power plan for these buildings, which would rely heavily on tidal generators and gravitational batteries — renewable energy sources that don’t pump greenhouse gases into the air.

“We’ve run computer simulations to analyze the thermal effects of heavy flooding in districts of Shanghai, Manhattan and Hamburg,” Gunnar Grün, Fraunhofer IBP deputy director, said in a statement.

“In each case, we applied climate models that projected sea-level rise and seasonal temperatures in the years 2100 and 2300,” Grün added. “Although the three cities are different in many ways, all were made significantly milder — more hospitable to humans — by the thermal inertia and evaporative cooling potential of water.” (Water has high “thermal inertia,” meaning it takes a relatively long time to heat up or cool down.)

IBP researchers also performed a variety of experiments. For example, they immersed wooden and concrete models in water and bathed them with radiation in the institute’s artificial-sunlight laboratory, and then measured evaporative-cooling rates and other variables.

Image 1 of 5Jonathon Keats and his colleagues constructed model buildings of different materials, which were subjected to a variety of tests at the Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics in Germany. Image 2 of 5Researchers measured the evaporative-cooling potential of the model “primordial cities,” among other variables. Image 3 of 5Artist and experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats. Image 4 of 5Some of the Primordial Cities model buildings, and other materials, are on display at the Berlin art gallery STATE Studio through Feb. 29. Image 5 of 5Ancient microbial mounds called stromatolites could be a model for how coastal cities survive rising seas in this era of rapid climate change, according to experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats.

“From these tests, we were able to gain initial insights into a range of potential building materials,” Grün said. “We were able to detect positive effects for both high-wicking concrete and treated wood, as well as vegetation-covered rooftops and facades.”

Keats used these and other data to construct small-scale skyscraper archetypes.

“The wood ones are especially interesting to me because the building materials can be grown on the roof, loosely paralleling how stromatolites adapt by growing,” Keats said in the same statement. “These skyscrapers are a cross between the Empire State Building and Abraham Lincoln’s log cabin.”

Stromatolites are also exemplars of efficiency, with each successive layer lapping up what its predecessors left behind. Live Science asked Keats if he envisioned his primordial cities shooting for something similar — say, by building each new skyscraper floor from the bones of the dead.

“I’m not against it,” Keats told Live Science. “But it would be very slow.”

Keats’ little buildings, along with results from the Fraunhofer IBP experiments and details of the energy management plan, are currently on display at STATE Studio, an art gallery in Berlin. The exhibition runs through Feb. 29.

If the show generates a sufficiently enthusiastic response, Keats would like to take the idea to the next level: a full-on field trial in a big city such as New York. The test would ideally involve the modification of multiple buildings and last at least a decade, he said.

A lengthy field trial would help work out the potential bugs in the primordial-city system. For example, which tidal generator design would prove most effective in a flooded city? And should femurs be the baseline construction bone, if planners do indeed go that route? Or would other, smaller bones add value as well?

Of course, this new perspective on design has some potential pitfalls. For example, the plan could stratify society even more dramatically (and quite literally) into the haves and have-nots, with the rich perhaps cornering the market on survivable real estate in coastal regions.

“There are many reasons why this could be a very bad idea,” Keats told Live Science. “So, that’s why it’s important to start prototyping now.”

Keats hopes the Primordial Cities Initiative paves the way for a new field of study he calls paleobiomimicry. Biomimicry is already a thing; engineers have based the design of many products on the fruits of nature’s evolutionary labor. (Velcro, for example, was inspired by thistles’ sticky burrs.) But paleobiomimicry looks to the distant past and takes a wider view, plumbing lessons and insights from entire ecological systems.

Keats wants humanity to tackle the root cause of climate change: the pervasive pumping of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. But, unlike some purists, he also thinks mitigation against global warming’s worst effects is worth pursuing, as his new project shows.

“Revolutions tend to be bloody and not well-thought-through,” Keats said. “We need to think. And to think, we need time.”

Sourse: www.livescience.com